Historical novels don’t shy away from blood and grime. Indeed, a kind of awestruck, mud-drenched realism is a staple ingredient of the genre. But more often than not the lovingly rendered scenes of terror and depravity are directed toward an edifying vision, a notion of progress. Those who suffered the depredations of the past did so, we suppose, that we might reap the benefits. In bumper-sticker terms, our freedom was paid for by their blood, sweat and tears.

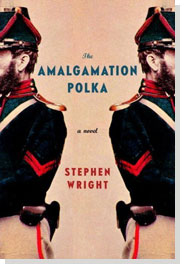

Stephen Wright’s Civil War novel “The Amalgamation Polka” is quite another sort of beast. It tells a superficially familiar, almost archetypal tale: A boy from a Northern abolitionist family, linked by blood to the Southern slaveocracy, goes to war, loses his innocence, sheds blood, survives and comes home. But for Wright, a cult hero of sorts who has one foot in the world of mainstream literary fiction and the other in postmodern experimentalism, uplifting lessons are in short supply amid the gore and filth.

For all the meticulously researched detail of “The Amalgamation Polka” — the increasingly gruesome list of thrown-away items to be found in the waters of the Erie Canal; the description of an unanesthetized dental extraction, at which onlookers are charged 50 cents; the chaos of death and dismemberment at the battle of Antietam; the visits to Manhattan freak shows and whorehouses — this book isn’t really about the 19th century or the Civil War at all. It’s about the nature of human existence, which Wright sees as an “elaborate practical joke,” behind which the incomprehensible threads of cosmic or metaphysical truth can sometimes be glimpsed or imagined. And it’s about America, which Wright understands — more so than even Thomas Pynchon and Don DeLillo, to whom he is often compared — as a collective state of delusion, a vicious, exciting and insane society poisoned at the root by the outrageous lies it has told itself.

Fans of Wright’s previous books (“Meditations in Green,” “M31: A Family Romance” and the amazing road novel “Going Native”) will expect this deep, dark current of wonder and despair — cynicism is too thin and pinched a word — an abyss so rich and black that at bottom it begins to shed a kind of light, as in Conrad or Blake or Coleridge. They will also have some idea of the roller-coaster power of Wright’s prose, which navigates fearlessly from grandiloquence to self-parody, delighting the eye, the mind and the ear. You may be skeptical about reading a book whose author aims to tell you that your country is hopelessly screwed and always has been, or a historical novel that seems, mysteriously, to be both the real thing and a merciless parody. But I don’t know who else in American fiction writes prose this good. Maybe Denis Johnson at his best, or Toni Morrison at hers. Maybe nobody.

Here is a sentence — one sentence — from an early chapter in which teenage Liberty Fish, our hero (yes, that’s his name) is traveling westward with his father aboard a packet boat on the Erie Canal:

“Someone had produced a fiddle around which soon congregated a makeshift chorus of willing singers, obscure figures in black cutout against the last fading light, and then the familiar strains of ‘Old Folks at Home’ rose up against the night in fluidly adroit, unforgettable harmony and it was possible to believe that the world and the things of the world were connected by a melody of their own, persistent though often indistinct, traces of which could be heard lurking even beneath the sentimental cadences of a popular tune of the day, and as the final note dissolved into a pure sustained silence, all noise and motion beyond the boat, the toiling mules, seemed to cease — even inanimate objects held their breaths — and into that becalmed interval glided, silent as a shade, the long, graceful packet and its entranced human cargo, as through a mystic cavern hewn from nature’s own stuff, and then the bow hit the strings (the opening bars to ‘Turkey in the Straw’) and the spell was broken, and time fell back onto the travelers’ shoulders like a cloak spun of material so gorgeously fine you didn’t even realize it was wearing you until it had been briefly whisked away.”

This is what lends Wright’s writing a kind of giddy ecstasy, even as his verdict on human nature and social-political reality, especially when it comes to these United States, is relentlessly negative: the idea that “the world and the things of the world were connected by a melody of their own,” which might be Buddhist theology and might be, I don’t know, string theory. Liberty Fish comes from a Christian abolitionist family in upstate New York (most antebellum abolitionists were what we might now call fundamentalist Christians), and while there isn’t much Jesus talk in “The Amalgamation Polka,” it struck me for the first time that Wright is fundamentally a religious novelist. He doesn’t share the Fishes’ specific faith — nor, perhaps, the specific faith of anybody else — but the idea that “this world was not what it seemed, that closely hidden behind the mundane affairs of the day lurked layer upon unexamined layer of outright strangeness,” as Liberty observes later, is too often repeated to be mere rhetoric.

In that undefined religiosity, or whatever you want to call it, and in the Faulknerian fulsomeness of his writing, Wright imbibes from the same font of American craziness and optimism he also mocks. In his author photo he looks every inch the aging boho hipster, with motorcycle jacket and multiple piercings; on the other hand, as his biographical blurb cryptically informs us, he “was educated at the U.S. Army Intelligence School.”

Wright’s title refers to a racist editorial cartoon of the period, which depicted “an amalgamation polka,” where whites and blacks dance together in genteel costumes. This was meant to suggest, one presumes, that other mutually enjoyable physical activities might occur between the races later in the evening. Race mixing was the great shibboleth of slavery advocates and segregationists from the dawn of American history almost to our own time, and many of the characters in Wright’s novel are obsessed with it. Liberty grows up in a house used as a station on the Underground Railroad, but his mother was raised on a large South Carolina plantation and his father is the scion of a Northern industrial family that has profited greatly from trade with the slave states.

Liberty’s parents are devoted to destroying the very institution that made their families rich, and this streak of altruism or perversity or whatever it is runs through the book. When Liberty finally visits the devastated Redemption Hall, his mother’s birthplace, near the end of the war and meets his maternal grandfather, the fearsome Asa Maury, the old man is as much a bitter, angry, hardened bigot as advertised. Yet he too, faced with the imminent destruction of slavery, is hypnotized by America’s racial dilemma — and in his own deranged Dr. Moreau fashion, is trying to solve it.

If these two households are like funhouse-mirror reflections of each other, Liberty’s journey from one to the other itself resembles a reckless, exhilarating and almost deadly carnival ride. He survives the horrors of Antietam, is briefly taken prisoner by the rebels, then deserts from the Union Army to go find grandfather Asa and sign on (or so the latter supposes) to his harebrained scheme to escape the collapsing Confederacy and hijack a ship for Brazil, where slavery remains alive and well. And that’s not even mentioning Liberty’s childhood, when he is educated by a one-eyed former slave named Euclid, taken carousing by his likable but degenerate Uncle Potter and sworn into the secret fraternity of pirates by a vagabond named Fife.

I said earlier that “The Amalgamation Polka” isn’t really about the Civil War or the 19th century, but considering all of Liberty’s vivid, uproarious and horrible adventures — which could have occurred at no other time and place — that’s not quite fair. It may be more accurate to say that Wright sees all the bloodshed and tumult of the period as especially good examples of the American madness his writing channels so effectively. Certainly he has drawn on various literary classics of that century as inspiration. My Salon colleague and friend Laura Miller has suggested (in the New York Times) that “The Amalgamation Polka” owes something to the absurd odyssey, and levelheaded protagonist, of “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland”; I would add that the combination of irony, melodrama and boy’s adventure yarn is reminiscent of “Great Expectations.”

Despite its elements of parody or self-parody, “The Amalgamation Polka” isn’t a joke, or at least not a cheap one. (It may be a joke in some grand existential or cosmic sense, but then so may all efforts at human expression.) Wright loads up the book with antique vocabulary-busters — I can’t tell you what “gallinipers” or “shecoonery” or “buckra” are, although I can guess at the meaning of “slantindicular” and “ramstuginous” — but his comedy is always laced with mania and sadness.

About two-thirds of the way through his journey to Carolina, Liberty spends the night with a Southern woman who hasn’t seen her husband in two years. Presumably a widow, she is raising her children alone on a half-abandoned Georgia plantation. They don’t have sex, although she asks to see him naked and he obliges. At one point, she looks at him with “the bleakest expression he had ever seen.

“‘This war,'” she says to him, “‘this horrible evil war, it’s never going to end. You do understand that, don’t you? Even after it’s over it will continue to go on without the flags and the trumpets and the armies, do you understand?'” It’s an idea often repeated in this book, one that runs through all the dreams of liberty and freedom shared in some form by Liberty Fish and all other Americans. Some may cherish the unrealizable vision of an amalgamation polka and others may fear it; all find themselves in a country endlessly at war with itself.