As it lied its way to war in Iraq, the Bush administration had powerful allies at the New York Times. Judith Miller, whose stenographic reporting on Saddam’s WMD helped the administration make the case for war, was the most notorious. And the intellectual support of Thomas Friedman, widely considered to be the most influential foreign-policy columnist in the world, was also key.

At the same time, the newspaper of record produced two formidable critics, who emerged from somewhat unexpected places. One was an economics professor named Paul Krugman, who from his perch on the Op-Ed page ventured far beyond the confines of the dismal science to savage the administration. The other was the paper’s former drama critic, Frank Rich, who used his feature-length column in the Arts & Leisure section (it was later moved to the Week in Review) to expose the way the Bush team manipulated the facts, staged events, intimidated critics, and generally created a convincing but utterly fake narrative about itself and its disastrous war.

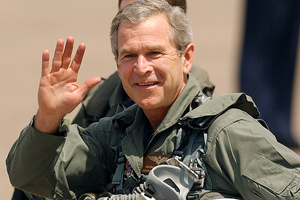

Rich’s columns had an instantly identifiable slant and tone. He had an unerring nose for the stench of corrupted truth, no matter how heavily doused in patriotic perfume. Rich combined his skills as a drama critic with his political savvy to “review” the banal, but brutally effective, Broadway play that Karl Rove, John Ashcroft and Bush’s other stage managers so masterfully produced. A kind of Everyman’s semiotician, Rich was unmatched at exposing the slick imagery (inevitably revolving around flag-waving and fear) that the Bush administration substituted for reality. And especially in the run-up and early days of the war, before the Times emerged from the fog of bad reporting and confused, timid editorial thinking that had plagued its coverage, his column was a much-needed shot of reality. For millions of readers thinking, “They didn’t really use that moth-eaten ‘Triumph of the Will’ set again, did they?” Rich could be a virtual sanity-preserver.

In “The Greatest Story Ever Sold,” Rich’s canvas is larger than his columns would ever allow — he’s dealing with the entire Bush presidency, not an individual scam or lie. The book isn’t as dazzlingly adroit as his best columns, but how could it have been? There are plenty of his trademark sharp aperçus, cultural comparisons and metaphorical skewerings here, but if he had approached the entire book that way it would have been all salt and no meat. Rich is smart enough not to push his politics-as-performance trope too far: In the end, he knows that politics is about power and its consequences in the real world, not some postmodern theory where everything dissolves into images. Accordingly, most of “The Greatest Story” is a straight, well-researched, clearly written narrative of Bush and his cohorts’ lies, deceptions and misdeeds, and of the cowardly and lazy press and “opposition party” that let him get away with them.

But even if Rich’s book is mostly a chronological retelling of familiar tales, it is invaluable as a comprehensive record of the tawdry machinations of a debased presidency, a kind of one-stop-shopping mall for all things truthy and Bushiful. Need a pithy, accurate account of the “Mission Accomplished” episode? Check. Need to refresh your memory about Bush’s various, contradictory accounts of his relation to “Kenny Boy”? Check. Searching for a record of bleak news bulletins that were immediately followed by sudden “revelations” of impending terrorist attacks? Check. Want a transcript of what Cheney actually said about the nonexistent link between Saddam and 9/11? Check.

Of course, Rich frequently displays his trademark Roland Barthes-with-a-remote chops, too. Explaining the failure of Bush’s sudden attempt to claim that the war had really been about spreading democracy, not WMD, he notes, “it was tantamount to ambushing an audience at a John Wayne movie with a final reel by Frank Capra.” Of Bush’s lame “inspiring” appearance in New Orleans’ Jackson Square after Hurricane Katrina, he writes that the carefully selected backdrop, St. Louis Cathedral, “was so brightly painted that it registered onscreen like a two-dimensional Mittel Europa castle painted on a backdrop for a nineteenth-century operetta.” But for the most part, the events he describes tell their own story — no commentary is really needed to explicate the Bush administration’s outrageously cynical political maneuverings.

Rich situates this sad story in a larger cultural frame, which he alludes to in his subtitle: “The Decline and Fall of Truth.” In a brilliantly incisive and damning epilogue — these 20 pages alone are worth the price of the book — he writes, “the very idea of truth is an afterthought and an irrelevancy in a culture where the best story wins.” That culture, he notes, took off in the mid 1990s, when “the American electronic news media jumped the shark. That’s when CNN was joined by even more boisterous rival 24/7 cable networks, when the Internet became a mass medium, and when television news operations, by far the main source of news for most Americans, were gobbled up by entertainment giants such as Disney, Viacom, and Time Warner. While there had always been a strong entertainment component to TV news, that packaging was now omnipresent … In this new mediathon environment, drama counted more than judicious journalism.” The Bush administration did not create this culture, he notes, but it “was brilliant at exploiting it to serve its own selfish reality-remaking ends.” To his credit, Rich does not claim that America’s infotainment culture was the decisive factor that allowed Bush to wage a war whose likely consequences, as he points out, could cause Bush to be judged the worst president in American history. But he is indisputably correct that it played an important role.

Of course, Rich is hardly the first to anatomize the decline of America’s news culture. Far more compelling — and originally argued — is his insight into the real reason Bush went to war in Iraq. His answer to this endlessly debated question, and his related excursus on the personality of Bush himself, may be the single most lucid and convincing one I’ve ever read. Although it is almost painfully obvious, and wins the Occam’s Razor test of being the simplest, it is put forward considerably less often than more ideological theories — whether about controlling oil, supporting Israel, establishing American hegemony, or one-upping his father.

Perhaps this is because Americans, in their innocence, cannot accept that any president would deliberately launch a major war simply to win the midterm elections. Yet Rich makes a powerful argument that that is the case.

Playing the key role, not surprisingly, is Karl Rove. “To track down Rove’s role, it’s necessary to flash back to January 2002,” Rich writes. The Afghanistan war had been a success. “In a triumphalist speech to the Republican National Committee, Rove for the first time openly advanced the idea that the war on terror was the path to victory for that November’s midterm elections.” Rove decided Bush needed to be a “war president.” The problem, however, was that Afghanistan was fading from American minds, Osama bin Laden had escaped, and the secret, unglamorous — and actually effective — approach America was taking to fighting terror wasn’t a political winner. “How do you run as a vainglorious ‘war president’ if the war looks as if it’s winding down and the number one evildoer has escaped?”

The answer: Wag the dog. Attack Iraq.

Now ideology comes in, along with the peculiar alliance of neocons and Cold War hawks that had been waiting for their chance. “Enter Scooter Libby, stage right.” As Rich explains, Libby, Cheney and Wolfowitz had wanted to attack Iraq for a long time, not to stop terrorism but for the familiar neocon reasons of remaking the Middle East and the familiar Cold War hawk reasons of trumpeting America’s might. “Here, ready and waiting on the shelf in-house, were the grounds for a grand new battle that would be showy, not secret, in its success — just the political Viagra that Rove needed for an election year.”

Of course, there was one little problem. What reason could team Bush come up with for attacking Iraq? “[A]bstract and highly debatable theories on how to assert superpower machismo and alter the political balance in the Middle East would never fly with American voters as a trigger for war or convince them that such a war was relevant to the fight against the enemy of 9/11 … For Rove and Bush to get what they wanted most, slam-dunk midterm election victories, and for Libby and Cheney to get what they wanted most, a war in Iraq for ideological reasons predating 9/11, their real whys for going to war had to be replaced by more saleable fictional ones. We’d go to war instead because there was a direct connection between Saddam and Al Qaeda and because Saddam was on the verge of attacking America with nuclear weapons.”

Of course, once the war in Iraq turned into a disaster and no WMD were found, the Bush administration had to do everything in its power to prevent the American people from learning that these reasons were lies. This is why Bush and his henchmen went after Joe Wilson.

This quick ‘n’ easy war was perfectly designed to appeal to George W. Bush. Rich draws a quick but brilliant sketch of Bush as a lazy, entitled boor, lacking in any real ideology beyond crony-capitalist Republicanism, who above all wanted to win and was accustomed to winning — because he had always played with a rigged deck.

Rove, “Bush’s brain,” dreamed of establishing a near-permanent Republican majority in Washington à la William McKinley. This was fine with Bush. “This partisan dream, not nation-building, was consistent with the president’s own history and ambitions in Washington. Bush was a competitor who liked to win the game, even if he was unclear about what to do with his victory beyond catering to the economic interests of his real base, the traditional Republican business constituency … Iraq was just the vehicle to ride to victory in the midterms, particularly if it could be folded into the proven brand of 9/11. A cakewalk in Iraq was the easy way, the lazy way, the arrogant way, the telegenic way, the Top Gun way to hold on to power. It was of a piece with every other shortcut in Bush’s career, and it was a hand-me-down from Dad drenched in oil to boot.”

It is now widely accepted that the Iraq war is one of the greatest foreign policy blunders, if not the greatest, in U.S. history. Some have gone further: The respected Israeli military historian Martin van Creveld argues that it is “the most foolish war since Emperor Augustus in 9 B.C. sent his legions into Germany and lost them.” Not a few regard Iraq as spelling the beginning of the end of American dominance in the world.

If Rich is right and Bush committed the worst military blunder in 2,000 years so that … drumroll please … the GOP could win the midterms, the Iraq war will single-handedly overturn Marx’s dictum that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, second as farce. For Iraq would then be both tragedy and farce — an idiotic reality TV show, hastily produced for sweeps week, in which the contestants actually die. A war that would require a Frank Rich to do justice to it.