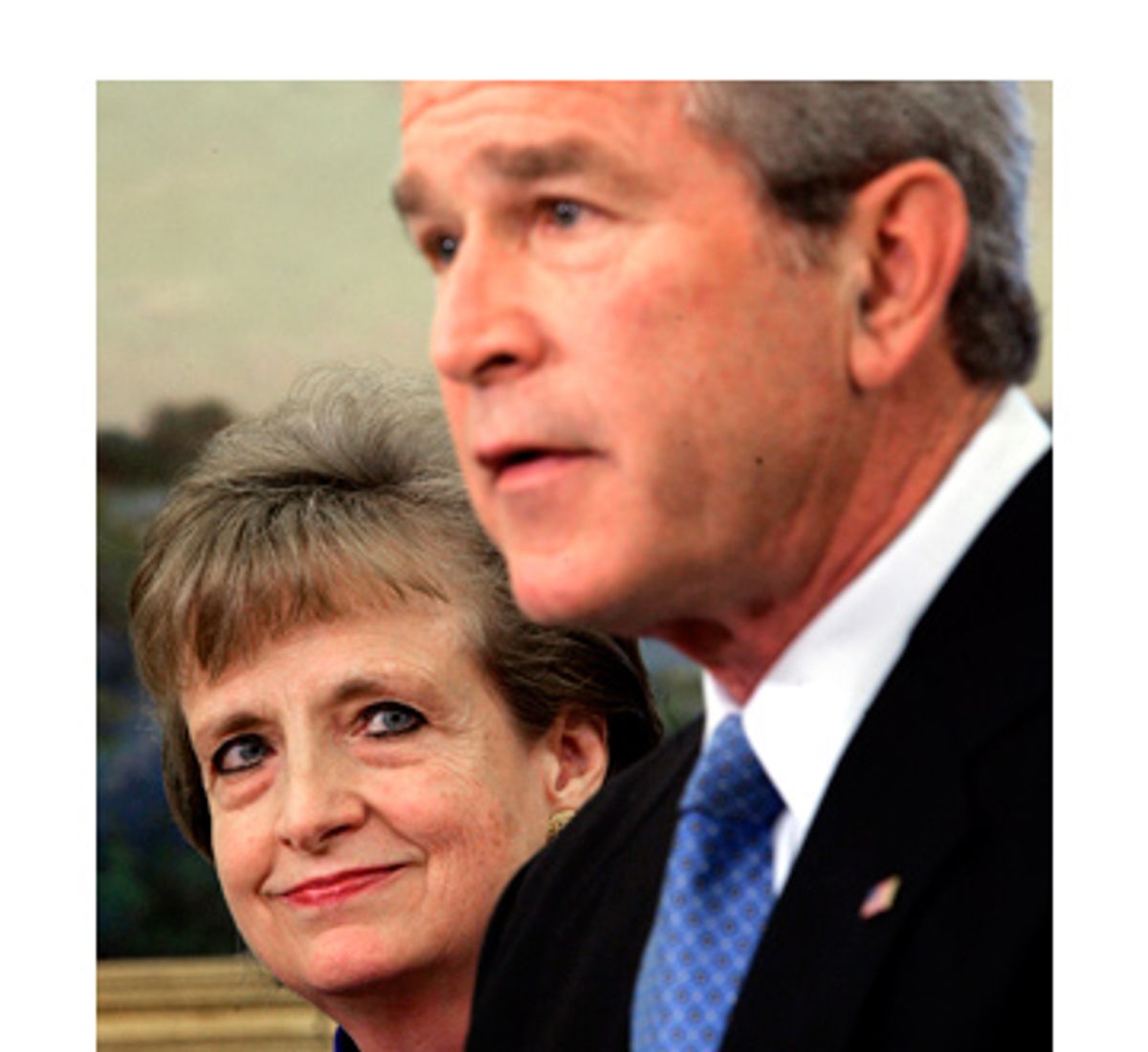

The Bush administration and its radical theories of executive power suffered yet another blow today from the judiciary, as a Federal District Judge, John D. Bates of the District of Columbia District Court -- a Bush 43-appointed (and generally very pro-Bush-administration) Judge as well as the former Deputy Independent Counsel for the Whitewater investigations -- held in a 93-page ruling (.pdf) that Bush aides Harriet Miers (former White House counsel) and Josh Bolten (White House Chief of Staff) are not entitled to absolute immunity from Congressional subpoenas. The dispute arose out of the investigation by the House Judiciary Committee into the firing of eight U.S. attorneys who, in many cases, had either aggressively prosecuted GOP officials or had refused to prosecute Democrats or otherwise advance the GOP's political interests.

As part of its investigation, the Judiciary Committee issued Subpoenas to Miers and Bolten in an effort to find out, among other things, who actually made the decision for those U.S. attorneys to be fired. The subpoenas ordered Miers to appear before the Committee in order to testify, and ordered both to produce documents to the Committee. Both Miers and Bolten refused to comply with the Subpoenas. Miers simply failed to show up for her hearing, while Bolten refused to produce the demanded documents. They did so in reliance on the Bush administration‘s claim that both of them, as top-level aides to the President, enjoyed absolute immunity from Congressional subpoenas. It was that extremist theory which the court today rejected -- and rejected decisively and unequivocally.

In unusually strong language, the court pointed out that the President's claim that his aides enjoyed absolute immunity from Congressional investigations was "unprecedented" and "without any support in case law" (p. 3). Like so many perverse claims of absolute presidential authority, this claim was plainly contrary to the core principles of how our country has long functioned: "Federal precedent dating as far back as 1807 contemplates that even the Executive is bound to comply with duly issued subpoenas" (p. 31). To underscore how frivolous the administration's claim here was, the court emphasized (p. 78):

The Executive cannot identify a single judicial opinion that recognizes absolute immunity for senior presidential advisors in this or any other context. That simple but critical fact bears repeating: the asserted immunity claim here is entirely unsupported by case law. In fact, there is Supreme Court authority that is all but conclusive on this question and that powerfully suggests that such advisors to not enjoy absolute immunity.

That the Bush administration's claim was purely lawless has long been obvious. After all, the Supreme Court, in 1974, already explicitly ruled (in the context of a criminal investigation) that Richard Nixon lacked exactly the absolute immunity that Bush officials claimed here. Because of that, as I wrote back in March, 2007 when this claim was first asserted by the Bush administration:

It is crystal clear (just as it was when Bill Clinton sought to invoke "executive privilege" to resist Grand Jury subpoenas to his aides -- Sidney Blumenthal and Bruce Lindsey and Hillary -- in the Lewinsky investigation) that the narrowly construed doctrine of executive privilege does not entitle the President to shield the communications here from compelled disclosure.

All along, the refusal of Bush aides to testify (and today's ruling obviously applies to Karl Rove as well) was nothing more than another lawless attempt by the administration to shroud everything it does in secrecy and shield itself completely from accountability of any kind. Indeed, as the court pointed out today, quoting a 1975 Supreme Court case, the power to compel testimony and documents from the Executive branch is indispensable to what are -- at least in theory -- the core Congressional functions of lawmaking and oversight (p. 36):

The power of inquiry -- with process to enforce it -- is an essential and appropriate auxillary to the legislative function.

Today's ruling should elevate the pressure on Bolten, Miers, Rove and other Bush officials to respond to Congressional inquiries regarding what they know about the firing of these U.S. Attorneys, but as a practical matter, its impact will be quite limited. Miers, Bolten and friends can still (and certainly will) assert privilege with respect to specific conversations and documents (the court only resolved whether they have immunity from Congressional subpoenas generally, not whether specific documents and conversations are privileged). This ruling simply means that Miers and Bolten must "respond" to the Subpoenas -- Miers can show up and refuse to answer most questions by relying on specific "privilege" assertions (that the court would then have to resolve), and Bolten can do the same with regard to documents. This administration has repeatedly demonstrated complete indifference to legal process.

The court did note, in several places, that Congress likely has (again, at least in theory) the inherent authority to arrest and detain Executive Branch officials who refuse to comply with their Subpoenas. But they have demonstrated no appetite for exercising that power, and short of something truly threatening like that, it is difficult to envision Bush officials being meaningfully forthcoming in any Congressional investigation.

One interesting point the court highlighted (p. 76) was that the next President could simply withdraw any claims of privilege over these matters. Even though Bush, as a former President, could still assert the privilege, its assertion "would necessarily have less force, particularly when the sitting President does not support the claim of privilege." Thus, an Obama presidency (assuming Cass Sunstein has no say in the matter) could significantly diminish the ability of Bush officials to shield their legally dubious conduct from Congressional and judicial scrutiny by formally withdrawing all of these claims of executive privilege -- not just as part of this investigation but the other scandals as well.

Little by little -- step by step -- federal courts have been fulfilling their function in rejecting the radical executive power claims of the last seven years and imposing some modest limits (at least in theory) on what the Executive Branch can do. That's why the Bush White House is so eager to obtain immunity and invoke every procedural weapon to avoid having to be accountable in a court of law. Today's decision is the latest such step in that process, and provides still further evidence of just how lawless this administration and its animating theories have been.

Shares