Glen Duncan doesn't exactly write thrillers and doesn't exactly write literary novels. Indeed, the 43-year-old English writer has developed an intriguing and soulful fusion of the two, churning out intricately plotted page-turners that'll keep you up all night while their protagonists wrestle with God, the modern world's loss of meaning and the painful and awful facts of recent history. In "Death of an Ordinary Man," Duncan's hero was a ghost, trying to sort out his family's damage from the other side; in his 2007 novel "The Bloodstone Papers," he focused on a writer of Anglo-Indian ancestry (like Duncan himself) who's trying to track down the legendary con man who ruined his father's life.

Augustus Rose, the narrator of Duncan's new novel, "A Day and a Night and a Day," isn't quite dead yet (although he's come pretty close), but he is another introspective, unsettled, mixed-breed character with a lot of unanswered questions about himself and the cosmos. In an all-time marvelous accident of literary timing, in fact, Duncan has written a book whose hero is essentially Barack Obama mixed with Bill Ayers. A biracial New Yorker (absent black father and overpowering Italian-American mother) and one-time '60s activist, Augustus has become involved with a shadowy, secret vigilante organization whose list of potential targets include both Islamic terrorists and President Bush.

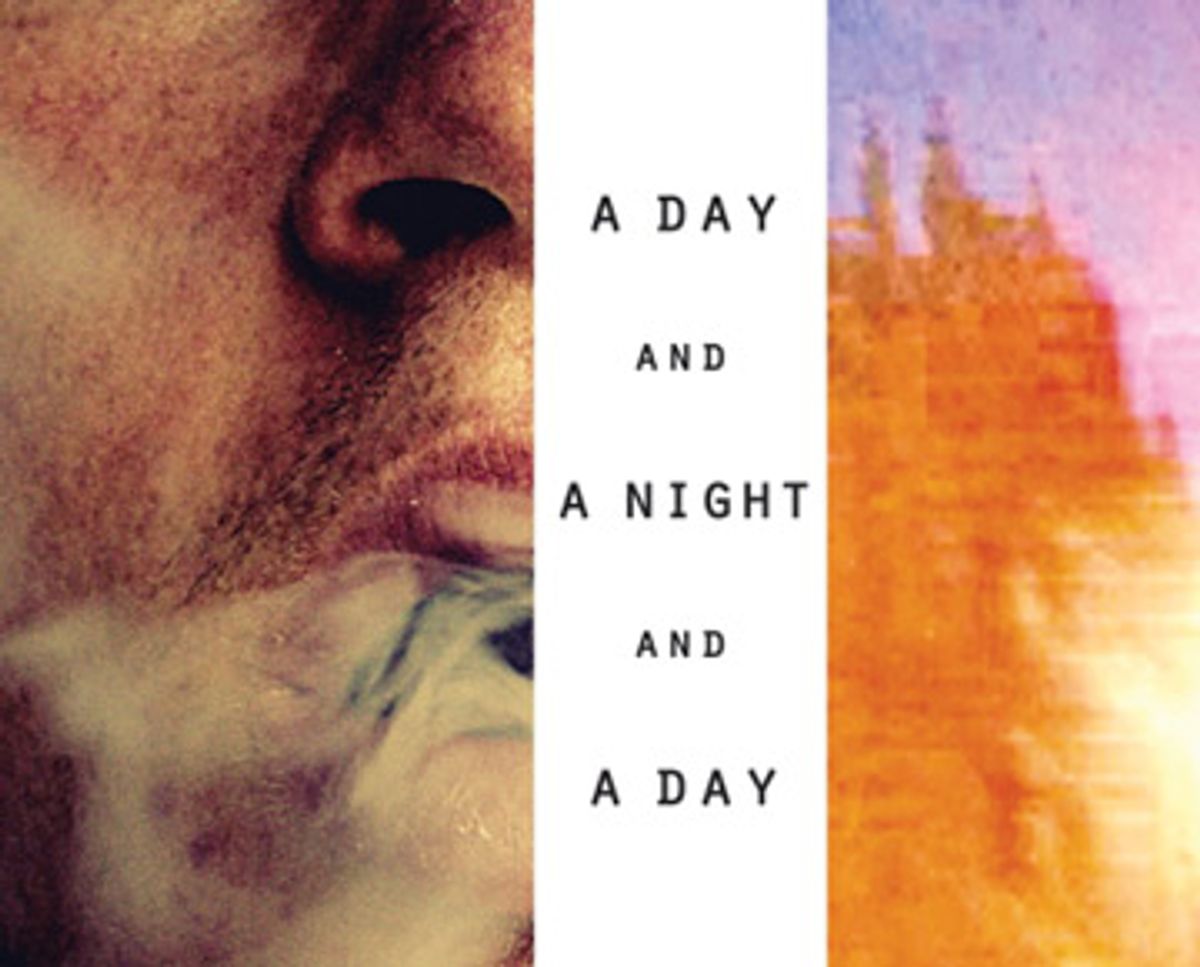

"A Day and a Night and a Day" is a puzzle box spring-loaded with surprises, so I'd better not tell you exactly why Augustus joins this movement after many years as a heartbroken, thoroughly apolitical Manhattan restaurateur -- oops, that was a clue! -- and spends two years posing as a Muslim convert in Barcelona. But here's what happens after that: He gets yanked off the street by persons unknown (I mean, OK, we have a pretty good idea) and spirited away to a "black site" interrogation facility that eventually turns out to be in Morocco. When he wakes up there, Augustus tells himself: "People use the phrase, 'the worst case scenario,' it's always contextual. Not here. This is the worst case scenario, the Platonic Form, of which all others are imperfect instances." He's right, and he hasn't even met Harper yet.

Duncan does interesting heroes. But in the tradition of John Milton and Hollywood, he does amazing villains. Harper is a good-looking young American clad in Gap casuals and an Ivy League accent; you could call him a downsized, 21st century version of Mick Jagger's Lucifer, a cynical, curious man of wealth and taste. Harper appears sane and literate, and maintains an attitude toward Augustus, even in their darker moments together, of "calm friendly alertness." If anything, he genuinely seems to like Augustus' tragic and ironic intelligence, remarking several times that they'd have been great friends or business partners under other circumstances. He compliments Augustus on his Morgan Freeman-like "gravitas," and admires his ability to withstand interrogation, even without such "first principles" as religion or a passionate political ideology. "I'm a fan of yours," Harper murmurs. "Narcissistically. You remind me of myself."

Harper has read Baudrillard's argument that America secretly wished for 9/11, and he agrees. He's personally disgusted with the stupidity and incompetence of the Bush administration; when the conversation turns to Augustus' group and its assassination plans, he jokes, "Obviously I see where you're coming from." Do Harper's wit and intelligence make things better or worse during the day and night and day when Augustus is mercilessly tortured, humiliated and, finally, shockingly disfigured on Harper's orders in a secret Moroccan jail? That is one, but only one, of the great and terrible mysteries in Duncan's novel.

There are a few more hints I can drop about "A Day and a Night and a Day" that may make it seem more inviting, without giving anything crucial away. The title does not simply refer to Augustus' time in the torture chamber but also to the time he spends with Selina, a daughter of the Upper East Side aristocracy and his lost love from the late '60s, during their unexpected reunion later in life. Secondly, the narrative's present tense is actually set after Augustus' terrible intimacy with Harper, when, half-crippled and exceptionally surprised to be alive, he becomes the first black man ever to live on the remote Scottish island of Calansay, where he strikes up an unlikely friendship with a teenage runaway pursued by a villain of her own. (I imagine Duncan has a genuine Scottish isle in mind, but the details of this one are fictional; it isn't quite Colonsay, in the Hebrides.)

Finally, while various heavyweight novelists and filmmakers have tried to grapple with the cognitive dissonance, not to mention the moral and existential costs, of the years since 9/11, Duncan does so almost casually, while spinning a gripping tale. His Dostoevskyan encounter between a philosophical inquisitor and his philosophical subject, each of them representing the promise and the danger of America in varying blends, is the darkest and most convincing account of the idiocies, insights and horrors of the "war on terror" that I've yet read. To judge by Errol Morris' "Standard Operating Procedure," mind you, most CIA interrogators lack the intellectual subtlety of Harper. Then again, you and I can only hope we never meet the really smart ones.

Shares