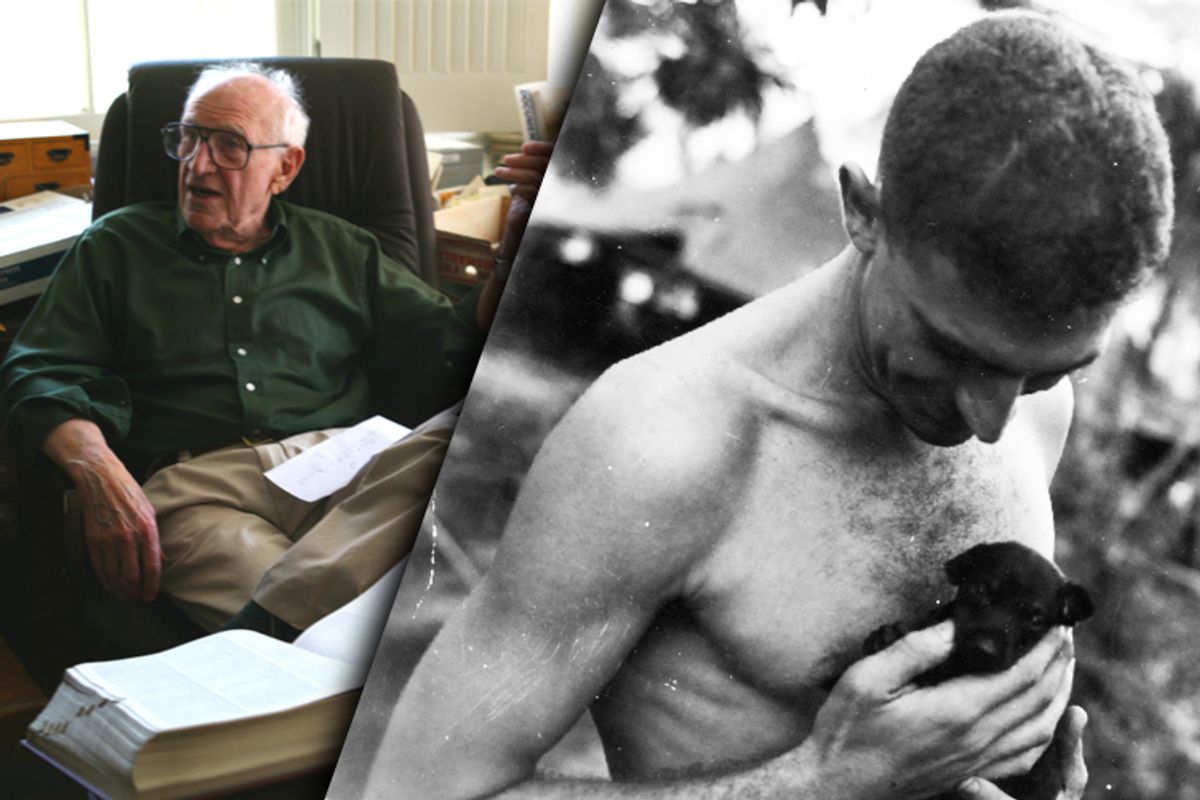

Millard Kaufman published two books with McSweeney’s -- his debut novel, "Bowl of Cherries," when he was 90 years old, and then "Misadventure," his posthumous final novel. Born in 1917 in Baltimore, Millard served in World War II and fought in Guadalcanal, Guam, and Okinawa. He is the cocreator of "Mr. Magoo," and wrote two Oscar-nominated screenplays. He led an extraordinary life, to be sure, and accumulated an impressive list of accomplishments. But the staff at McSweeney’s will remember him more for the stories he told. Endlessly self-deprecating, Millard was always telling stories, never failing to capture our attention with the breadth of his experiences. Below, Jordan Bass, Millard’s editor at McSweeney's, tells a story of his own about coming to know a writer, who, even after ninety-two years, still had much more to offer.

I first heard the name Millard Kaufman in September 2006, when McSweeney's was on the hunt for new books to publish; his agent had passed away, and his novel had made its way to us. Our books editor at the time, Eli Horowitz, sent me a few links as background: an IMDB page featuring Millard reminiscing about Humphrey Bogart ("a wonderful chess player"); an excerpt from "Shade of the Raintree," a history of the film "Raintree County," with a quote from the critic Bosley Crowther calling the screenplay (which Millard had written) "a formless amoeba"; a San Francisco Chronicle article which quoted Millard saying, "I don’t know how Sinatra was with other people, but around me he was very real."

We were dealing, in other words, with a writer who had survived half a century of Hollywood (he wrote a number of other screenplays besides "Raintree County," including the great "Bad Day at Black Rock"; Bosley Crowther liked that one better), a writer who seemed to have known everyone and had the stories to prove it. On top of all that, he had alighted in his late eighties with a finished manuscript for a novel of reckless youth. Eli and I passed the pages back and forth, agreed that it was fantastic, and bought it.

Millard had many more stories (he is the only first-time novelist I’ve met who could relate first-hand writing advice from Charlie Chaplin), but I came to know him through the novel -- "Bowl of Cherries," that first book, is the tremendously sharp, tremendously funny story of Judd Breslau, a fourteen-year-old child prodigy who recovers from being kicked out of Yale by chasing an Egyptologist’s daughter to Iraq.

It reads not at all like it was written by an eighty-nine-year-old, except for the wry inclusion of words like "bosky" and "thew" and "slubber"; it is a dead-on portrait of an addled young man, with a spirit of high-comedic adventure and an understanding love and ambition that those of us born after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles should only hope to match. We brought it out in 2007, at which time it had a very fine run as a small-press novel; Millard, meanwhile, celebrated his ninetieth year on this earth with a few events around LA (he wasn’t traveling anymore by then, or we would have sent him everywhere we could) and went to work on novel #2.

That book, "Misadventure," came to us in 2008. It was a more grown-up, darker story, although still full of the wit and romantic entanglements that peppered the prior one -- it was a noir this time, set in and around LA, exploring among other things the cratering real-estate market and several more deadly kinds of familial strife. Millard was as ready as ever to dig into it with us; as we got into the edits, he was already talking about the next story he wanted to write. It would be a Hollywood story, centered on powerful men older yet again than the teenagers of his debut or the just-shy-of-thirty schemers of the newer book; he would put down on the page the scandals and the skeletons his scriptwriting days had revealed to him. We couldn’t wait to see it.

Millard, though, was already ailing, by that time; as he finished up the work on "Misadventure," honing every double-cross, his health kept getting worse. He passed away on March 14, 2009, just after his ninety-second birthday. Our last conversation had been about his latest edits -- he had that same agile mind to the end, that same joy in the work. He was gone before we knew it.

A year later, though, having gone back to the book, and having enlisted Millard’s son Frederick, an author himself, to help us make a few last refinements we did our best to bring a bit of his voice back again -- "Misadventure," with all its luckless strivers and bloodthirsty vixens, hit shelves last month. Frederick’s own take on it is below; it’s a hell of a book, by a hell of a man. We’re thrilled to have known him, and to have worked with him, and we’re sorry he isn’t here anymore.

From the Afterword to "Misadventure "

My father died before the edits came through for this book, so the final calls fell to me. His death, lousy in all other respects, delivered a not unwelcome sense of déja vu: Although it was the first time Millard had died, it was not the first time I had edited this book.

The task initially fell to me when I was fresh out of college, earning less than minimum wage from a textbook publisher who worked the gifted-and-talented racket. I operated the freight elevator, and the boss called me Cheetah.

One day, Cheetah was summoned to a musty corner of the warehouse. Here, the boss informed me he was looking to expand his literary offerings beyond brain teasers and math problemoids, and did I have any ideas? I mentioned that my father had just finished a novel.

Millard had been writing novels ever since he became permanently pissed off at Hollywood for the treatment his friends and fellow citizens had received during the blacklist, and thus was born the exit strategy that would bear fruit half a century later, when he published "Bowl of Cherries" and became America’s most famous ninety-year-old boy novelist.

Back in my elevator-operator days, Millard was an unpublished novelist of sixty-six. Which was when I first became his editor.

It was fabulous, an Oedipal fantasy realized, a reversal befitting the search-and-destroy mission for a father at the center of the book in question. After all those years of him telling me how to write, the tables had turned.

We disputed our way through his prose. On the west coast, among his cronies gathered around the table of the Hamburger Hamlet, Millard must have made light of such redaction by his son, and I imagine he was not entirely displeased when six months down the line the boss once again summoned Cheetah to his bunker to say that all novelistic ambitions for the company had gone kaput. "Misadventure" would have to wait another quarter century to see the light of day. By not being published, the old man had won another round.

This time, the edit was easy, and not because the author wasn’t around to argue. Except for a spot here and there where the talented Jordan Bass asked for a clarification, I didn’t touch a word.

A week before he died Millard was too weak to talk but somehow, despite the needles and exhaustion, he would whisper a word or two for me to take down. For his next novel, he told me. Collaboration and irony to the very end, and beyond.

-- Frederick Kaufman, January 2010

Here's a short video of Millard that McSweeney's put together after publishing "Bowl of Cherries."

Shares