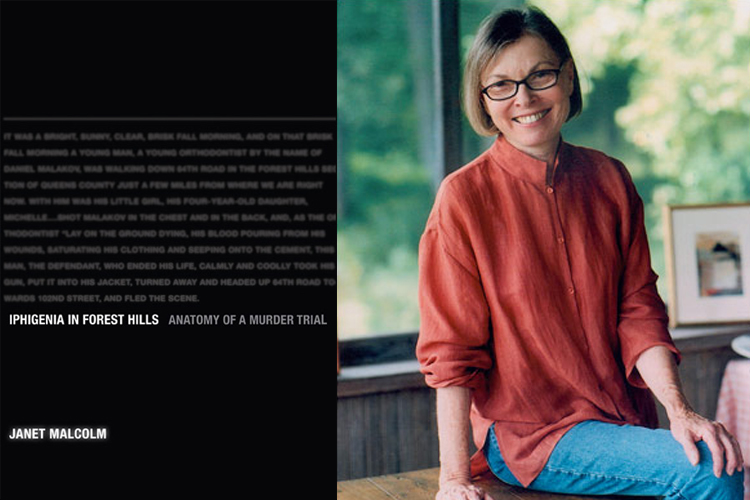

Janet Malcolm’s “Iphigenia in Forest Hills” is everything you think you don’t want in a courtroom drama. Expanded from a New Yorker article about the 2009 joint murder trial of a woman in Queens and the man she was convicted of hiring to kill her ex-husband, this slender book embraces ambiguity and uncertainty. The point of a trial is to establish what “really” happened and who is truly responsible, which is one reason why courtrooms have been the setting of so many satisfying fictions. But the shooting of Daniel Malakov as he stood with his 4-year-old daughter in a playground was no fiction, and there are times when insisting that a handful of facts be made to add up to a clear chain of events and an unqualified apportioning of blame leaves us not with justice but something that looks like its opposite.

Malcolm is a legendary journalist who has made journalism itself the subject of much of her work. Her mixed feelings about her profession are evident here, too, as she grits her teeth to ask the various players for interviews. “I have never come to terms with this part of my work,” she writes. “I hate to ask. I hate it when they say no.” You can’t help wondering why anyone says yes to Malcolm at this point; if you do, chances are you’ll come out looking bad, or at least not as good as most people prefer to see themselves. Fascinated as she is by her own ambivalence, Malcolm has a bloodhound’s nose for other people’s, and the world she explores in “Iphigenia in Forest Hills” is one in which nobody’s motives seem simple, let alone clean.

Mazoltuv “Marina” Borukhova, the woman at the center of this story, was a physician. She and her ex-husband, a dentist, belonged to an Orthodox Jewish sect from Central Asia called the Bukharans. Though their role in this immigrant community was a major focus of the New York Times’ coverage of the trial, for Malcolm it’s more of a side issue. Religion figured in the trial itself at one major point — when the various parties debated how to schedule closing arguments around the Sabbath. Still, that incident was telling: Borukhova agreed to violate the Sabbath prohibitions against traveling after sundown on Fridays, but only for one weekend out of two. Her stubbornness in this intermittent and seemingly arbitrary piety was typical: She is a woman of baffling motivations, who rubs everyone the wrong way.

Malcolm freely admits her “sisterly” sympathy with Borukhova at the outset. By the end of the book, the only thing this reader felt sure of was that Borukhova didn’t get a fair shake. The judge, Robert Hanophy (a man with “the faux-genial manner that American petty tyrants cultivate”), made his bias in favor of the prosecution abundantly clear. He also rushed closing summations so the trial wouldn’t interfere with his Caribbean vacation. The result of this was that Borukhova’s attorney was forced to prepare his summation overnight and deliver it in a stammering, sleep-deprived condition, while the prosecutor had the whole weekend to prepare his. Malcolm asserts that “a trial is a contest between competing narratives” and that an attorney’s performance of his or her narrative matters more to the outcome than any purportedly objective consideration of the evidence. Borukhova’s attorney, though talented, was forced to defend her at this key moment under a considerable handicap.

Borukhova was engaged in an ugly custody dispute with her ex; this was, the prosecution argued, her motivation for hiring a cousin by marriage to kill him. The “navel of the case,” as Malcolm puts it, was the extraordinary decision by a family court judge to transfer custody of the daughter, Michelle, from mother to father. The sole reason for this was the child’s refusal to “bond” with her father (she cried hysterically and clung to her mother during court-appointed visits); Michelle was otherwise healthy, happy and well cared for. Malcolm attributes the judge’s “radical ruling” to a “fit of pique” triggered by Borukhova’s irritating personality and fanned by the influence of David Schnall, the child’s court-appointed law guardian.

Malcolm’s own narrative takes its strangest turn when Schnall becomes one of those people who agree to be interviewed. In a phone conversation (not the interview itself, which he insisted would have to wait until after the trial), Schnall treated the reporter to a bizarre, hour-long diatribe about how the world is run by a secret Communist conspiracy that has engineered everything from 9/11 to “the phony global warning agenda” to a decrease in “the male sperm gene.”

Schnall’s hatred of Borukhova, Malcolm argues persuasively, has been a deciding factor in her fate from the moment he was appointed as Michelle’s advocate. Malcolm found her conversation with him so disturbing, “I did something I have never done before as a journalist. I meddled with the story I was reporting.” She called Borukhova’s attorney and faxed him her notes. It did little good because, as Malcolm eventually learned, Schnall was well-ensconced in the Queens judicial system and was someone Hanophy and other judges knew and liked to work with. Ostensibly acting in the “best interests” of Michelle, he was in truth serving “at the pleasure of the Court.” In fact, Schnall had never even spoken with the little girl in whose life he had taken such an important role.

Michelle is the Iphigenia of this book’s title, the counterpart of the girl of Greek myth who was sacrificed by her father, Agamemnon, so that his fleet might sail to the Trojan War, and then avenged by her mother, Clytemnestra, who stabbed her husband when he returned. For Malcolm, Michelle is a child whose welfare is used as a pretext in battles among adults, but whose actual interests and happiness are overlooked. There could be no more eloquent proof of this than the fact that no one has been able to establish where Michelle was for many hours after her father’s murder. She seems to have been literally forgotten.

“Iphigenia in Forest Hills” is only an unsatisfying book if you can’t be bothered to think hard about what satisfies you. “Journalism is an enterprise of reassurance,” Malcolm writes toward the end. “We explain and blame. We are connoisseurs of certainty.” By refusing to do any of that, Malcolm has, in a mere 155 pages, given her readers far more than reassurance.