Editor’s note: This review, although rewritten and expanded, reuses material from Andrew O’Hehir’s original review of “The Ides of March” from the Toronto International Film Festival.

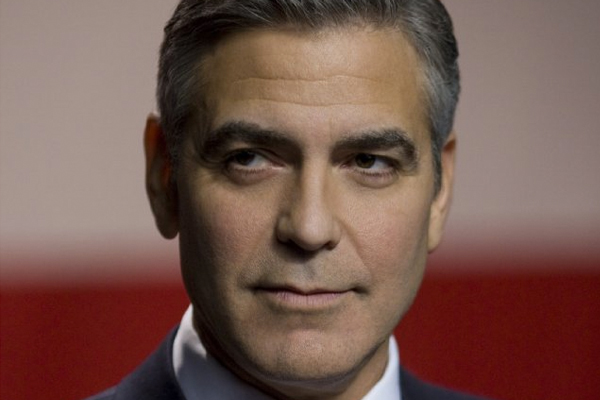

George Clooney’s film “The Ides of March” is an ingenious construction, much cleverer in psychological and symbolic terms than the story it tells, which mixes a schematic thriller and an on-the-nose fable about the corruption of American politics. The movie revolves around three confrontations between Clooney himself, playing a Pennsylvania governor turned presidential candidate named Mike Morris, and Ryan Gosling, as his hotshot, 30-year-old media strategist, Stephen Meyers. Only the last of those meetings is crucial to the ostensible plot of “The Ides of March,” which is about Stephen’s seduction and betrayal by pretty much everyone else in the movie (and most of all by himself). Taken together they tell the whole story.

Many critics, including me, have observed that Gosling plays something like a “George Clooney character” in this picture, while Clooney, as has become customary in his directorial efforts, consigns himself to a supporting role — in this case an instrumental but mysterious one. It will be lost on exactly nobody that these Gosling-Clooney scenes have an Oedipal character, both within the world of the movie and within the meta-universe of movie-star culture. In the first face-to-face between Stephen and Morris, at a crowded staff meeting where the strategist convinces the candidate to make an important policy shift, their mutual admiration is evident — but so is the tension, and the unstable power dynamic. Clooney’s Morris regards his young protégé with a hooded poker player’s smile; he admires the younger man’s energy and enthusiasm, but knows something he doesn’t. Gosling’s Stephen looks at his candidate with love — there’s no other word for it — but it’s the jealous, ambitious love of a favorite son. He sees Morris as the man he would like to become someday. By the end of the film, when the two meet in a darkened restaurant kitchen to strike the shadiest of backroom deals, Stephen sees Morris as the man he will become, or has already become. It isn’t pretty.

Then there’s the middle scene between Stephen and Morris, an apparent throwaway where the two of them have a brief conversation during a patch of turbulence on a chartered campaign jet. Stephen’s a nervous flier who clings to his armrests; Morris, a cool customer with a permanently sardonic demeanor — he’s an unlikely candidate for all kinds of reasons, and that’s only one — barely notices the bumps and stays focused on the papers in front of him. Stephen tells his boss that at moments like this he clings to the faith that they’re doing the right thing and fighting the good fight, and if you do that nothing bad can happen. Morris barely looks up. “Is that your personal theory?” he asks derisively. “Because I could shoot some holes in it: Roberto Clemente, on a humanitarian flight?” (At the risk of being condescending, I’ll elaborate: Clemente was a beloved baseball superstar who died in a 1972 plane crash, on his way to deliver emergency earthquake aid to Nicaragua.)

If you view Morris’ Clemente story as a parable — God offers no guarantees, and Stephen’s idealism is misplaced — it tells you almost everything you need to know about the politics of “The Ides of March.” Another of the terrific supporting characters in this movie, a battle-hardened New York Times reporter named Ida Horowicz (Marisa Tomei, for once getting a role where her sex appeal is irrelevant), sums it all up in an early scene with Gosling’s Stephen. “You’ve really drunk the Kool-Aid!” she tells him, amazed. “I have, and it’s delicious,” Stephen responds. He doesn’t care whether Morris can win, according to conventional wisdom; he believes that Morris must win, for the good of the country. Ida laughs, and assures him that who wins or loses makes no difference to ordinary people. The results will decide whether Stephen works in the White House for a few years or retreats into a K Street consulting firm, but that’s about it. “He will let you down,” she says. “They all let you down, sooner or later.”

Clooney’s title refers to the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C., which is sometimes understood as an effort to overthrow despotic rule and restore the Roman Republic. You can say that “The Ides of March” (adapted from Beau Willimon’s play “Farragut North”) depicts a more mundane kind of political coup, and a society moving in the same decadent direction, but it’s not at all clear where Clooney sees the parallel, or who in the film plays the roles of Caesar and Brutus. This is Clooney’s fourth feature as a director, and he’s developed into an understated craftsman with good storytelling instincts, an old-style Hollywood desire to let his actors tell the story and an interest in exposing the backstage machinery behind social spectacles. (“Confessions of a Dangerous Mind” was about television, “Good Night, and Good Luck” about the intersection of TV news and politics, and “Leatherheads” about the early years of professional football.)

Clooney’s character here, a populist Democrat who’s leading a tight race heading into the Ohio primary, suggests a combination of Barack Obama, Bill Clinton and John Edwards. (If that verges on being a spoiler, forget I said anything.) He plays the role of a fire-breathing populist revolutionary in public, but maintains an acerbic distance from even his closest advisors. At first glance, and even at second, Morris is a dream candidate, a sitting governor who has balanced his state budget and advocates an ambitious program of national renewal: mandatory service for high-school graduates, balanced with free college tuition and healthcare for all. He’s pro-gay marriage and wants to jack up taxes on the rich, and he’s an agnostic or atheist who declines to discuss religion, which may be the most unlikely element of all. If Morris may not entirely be what he seems to be — or at least as the star-struck Stephen views him — what candidate ever is? Clooney may be inviting us to consider whether that really matters, or suggesting that in the contest between idealism and pragmatism, one side is always sacrificed to the other. (Clooney gets a screenplay credit, along with co-producer Grant Heslov and playwright Willimon.)

What you get out of “The Ides of March” largely depends on what you bring into it. If you already believe that American electoral politics is a hopelessly cynical and corrupt shadow-play, where high-minded rhetoric is used to conceal a naked power struggle for the reins of a decaying state apparatus and the results (as Horowicz says) don’t matter to most citizens outside the Beltway, then that’s what the movie’s about. Other conclusions are possible: Maybe electing somebody with Mike Morris’ positions is important even if he’s a ruthless, calculating, lying bastard in private; maybe our focus on political buzzwords like “character” and “integrity” is where the real hypocrisy lies. I once had a conversation with Bill Moyers where he told me that he was never much concerned with a politician’s personality or private life; he had worked for Lyndon Johnson, who was (to put it generously) a mean-spirited and difficult person with numerous private failings, but also a highly effective president. We see Morris in pieces, some of them damning and others endearing (there’s a brief and wonderful scene in a limo between Clooney and the terrific Jennifer Ehle, who plays his wife), but we don’t get to know him well enough to render a final judgment.

As I said earlier, “The Ides of March” is the story of a young innocent’s seduction and betrayal, and I’m not talking about the comely 20-year-old intern named Molly (Evan Rachel Wood), with whom Stephen winds up in bed a few days before the Ohio primary. (She is no more than a contrivance, and one of the movie’s biggest weaknesses.) By Ryan Gosling standards, Stephen is a highly distracted playboy; even while they’re in the supposed throes of passion, Stephen can’t keep his eyes off the TV set, where Morris is refining his position on gay marriage. (Yeah, that’s a nice touch!) Morris is locked in a neck-and-neck contest in the Buckeye State with his last remaining challenger, an Arkansas senator named Ted Pullman who plays no role in the story. (Once again, the politics seem pretty vague: Pullman is described as a “tax-and-spend liberal,” but also one who taunts Morris for his lack of religiosity.) In this moody landscape of jargon-rich, warlike dialogue and gray, end-of-winter Cincinnati streets — the superb cinematography is by Phedon Papamichael — Stephen’s big crisis blows past so fast, like a truck on the interstate, that neither he nor we notice it till it’s gone.

Morris’ bulldog campaign manager, Paul Zara, is another great, gruff, growly role for Philip Seymour Hoffman, who might just fill up the supporting-actor category in this year’s Oscars all by himself (after his role in “Moneyball” as Oakland A’s manager Art Howe). He relies on Stephen, who is younger, better looking and arguably more intelligent, without remotely trusting him. Meanwhile, Pullman’s campaign manager, Tom Duffy (the terrific Paul Giamatti, smooth as a buttered walrus), makes a devious play to lure Stephen to his side, hinting that things he doesn’t know about yet will sink the Morris campaign. As soon as Stephen meets Duffy in a deserted Cincinnati sports bar for a bit of ass-kissing and horse-race chatter, events are set in motion that no one can control. Throw in Tomei’s ruthless Timester, who befriends Stephen before she backstabs him, and Jeffrey Wright as a thoroughly loathsome North Carolina senator who has dropped out of the race but controls 350-plus crucial delegates, and it all becomes a baffling, fast-moving game of who’s playing whom, and to what end. Stephen, Morris, the two campaign managers and Molly are all plunged down the slippery slope of sleaze and tragedy.

I’m not quite sure whether to describe the ambiguity and/or irresolution at the heart of “The Ides of March” as a strength or a weakness. The movie has nothing to say about American politics we don’t already know, i.e., the system is broken and dirty, and those who enter it are soon stripped of their ideals and reduced to viciousness. Maybe it’s perfectly fine for Clooney to suggest two contradictory conclusions; he’s trying to make stylish, thought-provoking pop entertainment, not write an essay for Harper’s. On second viewing, though, I’m not sure “Ides of March” is about politics at all. Its dense drama and characters and atmosphere all orbit its two dark pole stars, the twin ladykillers of different generations, both so grave and so ironical, both desired and/or envied by the rest of us. They gaze into each other like Narcissus looking into the pool, one of them a young man who still looks into the future with hope, the other an older man who knows better.

“The Ides of March” opens this week nationwide.