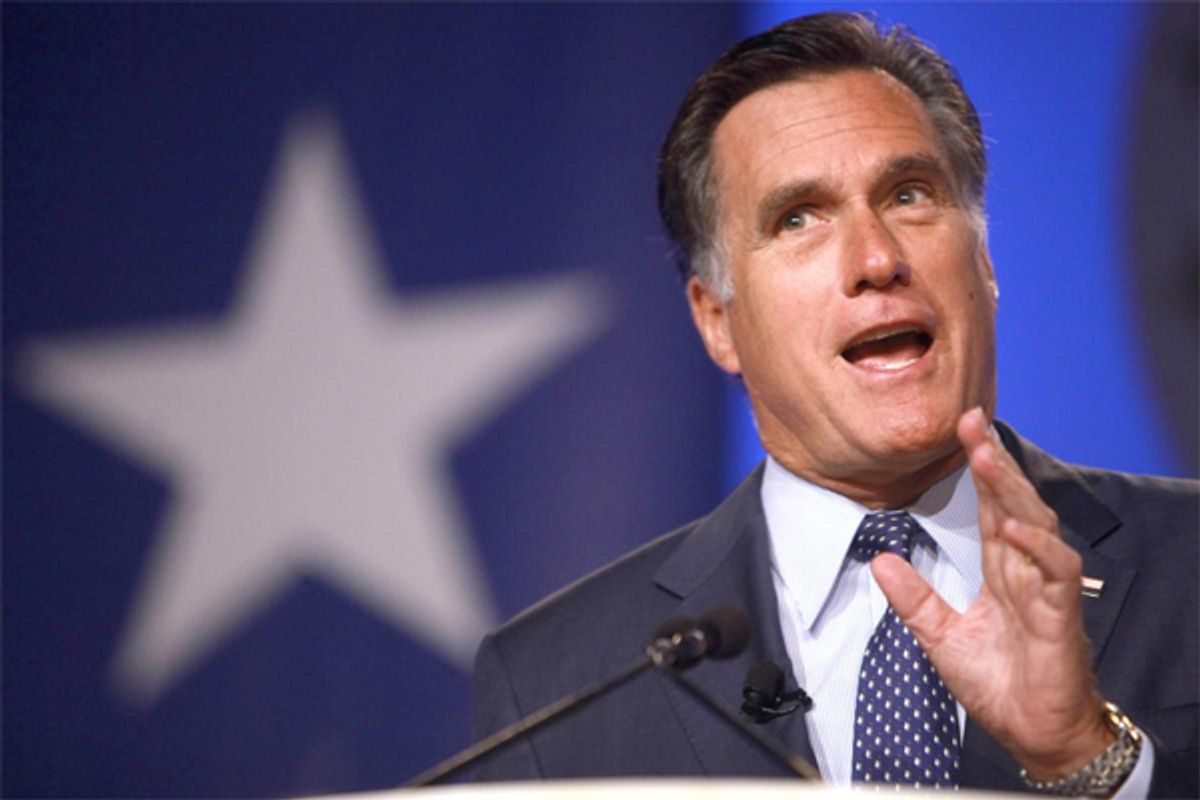

The funny thing about Mitt Romney's campaign for the GOP nomination is that for more than a year he's seemed to be perpetually on the brink of either melting down (because so many conservative really don't want him) or running away with the race and locking up the nomination early (because there just aren't any other options).

This is why he's faced a dilemma in Iowa, whose lead-off caucuses are now about 10 weeks away. If he can somehow win the state, it will all but assure Romney of putting together a one-two punch that has eluded every Republican candidate in the modern era, a development that would probably hasten the end of the GOP primary season. But ideological true-believers and fundamentalist Christians hold disproportionate sway in the caucuses, so any problem that Romney has with the party's base figures to be amplified there. The risk is obvious: An aggressive push to win the state will create high expectations -- and serious fallout if Romney fails to meet them.

So for most of this year, Romney has followed the example of John McCain, who made infrequent trips to the state four years ago, skipped the Ames straw poll and maintained a modest campaign presence in the state. This allowed McCain to swoop in just before the caucuses, as his poll numbers were rising everywhere, and nab 13 percent of the vote, a showing that was widely interpreted as better than expected and a sign of momentum. Five days later, McCain bested Romney, who had finished second in Iowa, by 5 points in New Hampshire, cementing his status as the front-runner.

Mimicking the McCain strategy seemed particularly wise two months ago, when Rick Perry entered the race and immediately rode a wave of conservative excitement to a double-digit lead over Romney in the state. But since then, Perry's standing has plummeted, and the most recent polling in Iowa puts him in single digits. Romney's main competition is suddenly Herman Cain, at least for now, which surely makes playing for an Iowa win more tempting. After all, Cain hasn't been spending any time in Iowa, has essentially no organizational footprint in the state, and doesn't seem interested in changing course. At least on paper, he's a far less intimidating opponent than Perry. There's also the possibility that Cain, Perry, Michele Bachmann and others will all end up with pieces of the conservative vote in Iowa, giving Romney a chance to win the state with, say, 30 percent.

Romney is actually in Iowa today, the first time he's set foot there since August, and naturally the question of how seriously he'll contest it has already come up. The answer he gave at an event in Sioux City seems cryptic: "I would love to win in Iowa, any of us would. So I will campaign here. I intend to campaign in all the early states at least, maybe all the states at some point." That could mean that he plans to ratchet up his efforts, or it could just mean that he'll make only a handful of appearances between now and January. He's still hedging his bets, it would seem.

If Romney does somehow win Iowa, he'll almost certainly win New Hampshire, where he's already the clear front-runner. This would be unprecedented; since Iowa became a key GOP test in 1980, no one has managed to win both states. That Romney has the potential to do so may be the most bizarre aspect of what has already been a truly odd GOP race. Just consider the trouble that GOP front-runners far more formidable than Romney have found in the Iowa/New Hampshire combo:

1980: Ronald Reagan entered the race as the clear, overwhelming favorite for the nomination, then suffered an unexpected 2-point loss to George H.W. Bush in Iowa. Bush, then a relatively obscure former CIA chief/ambassador/RNC chairman/congressman who was running as a socially liberal Rockefeller Republican, declared that he had "the Big Mo" and surged into contention in New Hampshire. But the gap between the contests was more than a month long back then, and Reagan managed to regain his footing -- some well-crafted theatrics helped -- and win a decisive victory over Bush, 50 to 23 percent. Besides a blip in Pennsylvania two months later, Reagan rolled to the nomination from there.

1988: Bush, after spending eight years reinventing himself as a true believer conservative while serving as Reagan's V.P., seemed well-positioned to inherit the GOP throne. But then came his humiliation in Iowa, where he finished with just 19 percent, behind not just Bob Dole (37 percent) but also Pat Robertson (25 percent). The campaign immediately moved to New Hampshire, whose primary would be held a week later, and within three days polls showed Dole overtaking Bush there. But a last-minute barrage of Bush ads attacking Dole for "straddling" on taxes and Dole's refusal in the final pre-primary debate to sign the traditional New Hampshire anti-tax pledge helped propel Bush to a campaign-saving 37-28 percent victory. He didn't lose another contest after that.

1996: This time Dole was the next-in-line candidate, and national polls in early '96 put him more than 25 points ahead of his rivals. Expectations in Iowa were particularly high, given Dole's strong performance there in '88, so it was something of a blow when Dole only nabbed 27 percent of the vote, just 4 points ahead of Pat Buchanan. A week later, Buchanan pulled off an even bigger surprise, winning New Hampshire. Initial returns in New Hampshire suggested Dole would finish third, behind even Lamar Alexander, news that supposedly prompted Dole to tell his aides that he'd drop out of the race. But the final tally put Dole in second place and the GOP's panicked establishment rallied around him, desperate to stop Buchanan. He righted his ship with a solid win in South Carolina, survived a brief scare from Steve Forbes (who posted wins in Delaware and Arizona), and pulled away.

2000: George W. Bush assembled perhaps the most formidable primary season bandwagon ever seen, gobbling up endorsements from key party leaders and raising tens of millions of dollars more than his opponents. The sense of inevitability around his campaign was so strong that six candidates -- Alexander, Elizabeth Dole, Dan Quayle, Pat Buchanan, Bob Smith, John Kasich -- all dropped out in the summer and fall of 1999. Bush had little trouble winning Iowa, where his main competition was Forbes, but then came a jarring 19-point loss to McCain in New Hampshire. The result turned McCain into a national political celebrity overnight. Money poured into his campaign, his poll numbers soared, and some Republican leaders even began rethinking their loyalty to Bush. But Bush, in a two-week period still remembered for its ugliness, stopped McCain's momentum with a solid win in South Carolina. In the process, Bush convinced the base to regard McCain as a tool of "mischievous" Democrats and their media allies, which limited McCain's post-South Carolina successes to blue states with open primaries. The race was over by early March.

2008 was a little different, since there was no clear front-runner when Iowa rolled around. Romney had the chance to emerge as one by winning the state, which probably would have pushed him past McCain in New Hampshire and set him up to win the nomination. Instead, he lost by 9 points to Mike Huckabee, ensuring that Huckabee would be a significant player in the South and making it easier for McCain to win New Hampshire the next week. So Romney has been stung by Iowa before. But the opportunity to win it this time around may be there. In other words, it's at least possible that one of the weakest front-runners either party has ever seen could end up winning the nomination without losing ... anywhere.

Shares