The chorus of Republican voices now raising doubts about Newt Gingrich (and, in some cases, bluntly attacking him) represents an obvious threat to the new GOP presidential front-runner. But the assault doesn't have to sink him. In fact, it could actually fortify Gingrich's position as the conservative movement's consensus alternative to Mitt Romney.

At least that's the lesson suggested by a pivotal episode in Gingrich's political rise that played out 21 years ago. Then as now Newt found himself targeted by influential Republican players, who saw an opportunity to undermine his influence within the party and arrest his career growth -- only to watch their efforts backfire and accelerate Gingrich's climb to the House speakership.

It was the fall of 1990 and a budget compromise struck by President George H.W. Bush and the leaders of both congressional parties provided the backdrop. With the annual deficits that had exploded under Ronald Reagan showing no signs of slowing, Bush agreed to back off from the signature promise of his 1988 presidential campaign -- "Read my lips: No new taxes!" -- in exchange for Democratic support for cuts in entitlement spending. From activists on the right, there was grumbling. They'd never fully trusted Bush, who had run against Reagan as a supply-side skeptic in the 1980 GOP primaries, and had been suspicious of his ideological transformation as Reagan's V.P. The "Read my lips" pledge had been a sop for them, and now here Bush was breaking it less than two years into his term.

But while the Republican Party's electorate had been steadily moving to the right, its Capitol Hill leadership was still largely cut from Bush's cloth, with two pragmatic deal-cutters, Sen. Bob Dole and Rep. Robert Michel, heading each chamber's GOP minority. Dole and Michel had joined with their Democratic counterparts, Sen. George Mitchell and Speaker Tom Foley, to craft the budget accord with the Bush White House, and the package was expected to clear Congress over the objections of ideological backbenchers on both sides.

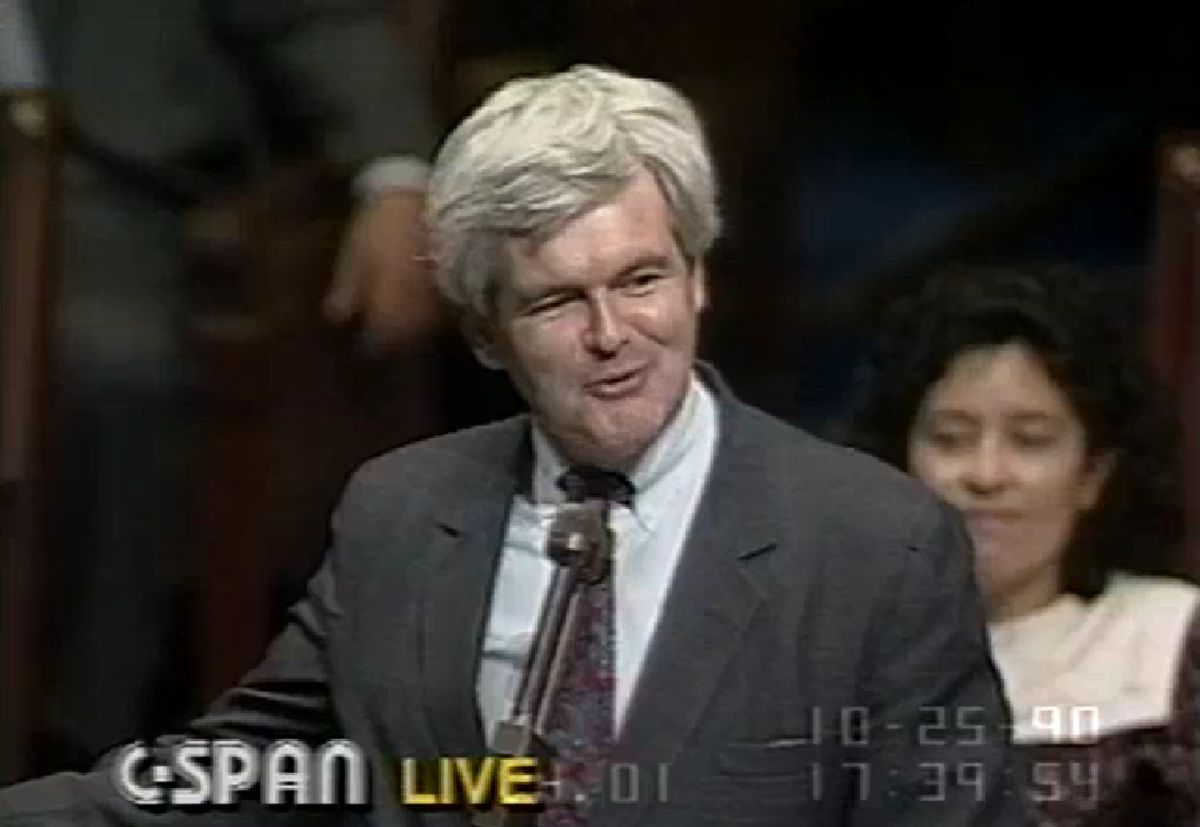

Which is where Gingrich came in. Elected to the House on his third try in 1978, he'd made a name for himself in the '80s as the voice of a new, more partisan and combative breed of Republican, one that tended to regard the Democratic Party as the enemy of freedom -- and any Republican who would compromise with a Democrat as a sellout to the cause. In his early days in the chamber, Gingrich and his allies were a lonely gang, infuriating colleagues on both sides of the aisle with their vitriolic grandstanding, often performed in after-hours speeches to an empty House chamber that were beamed out to a national audience by C-Span, which was then in its infancy. But with every election, the old guard's ranks would shrink a little more, with a corresponding number of Gingrich-style conservatives taking their place. By 1989, Gingrich had the votes -- just barely -- to stun Ed Madigan, the handpicked candidate of Michel, in the race for minority whip. The one-time gadfly had become the second-ranking Republican in the House.

So when, a year and a half later, the budget deal was struck, Gingrich sensed an opportunity, called the package a jobs-killing betrayal of principle, and vowed to fight it. ''I didn't do this lightly,'' he said. ''My intention is not to embarrass the president. My intention is to help this country to get an agreement which will increase jobs, improve the economy, create more revenues for the government and create more take-home pay and opportunity for Americans.''

Instantly, Gingrich's move changed the math in the House. With the No. 2 Republican in the chamber blasting the deal, backbenchers now had cover to oppose it themselves. The White House and its allies swung into action to quell the insurrection. John Sununu, Bush's chief of staff, warned House Republicans in a closed-door session that the president would personally campaign against them in the upcoming midterm elections if they didn't fall in line. Michel branded the objections of Gingrich and his crew "a thousand points of spite." But when the vote was called in early October, 60 percent of the Republicans in the House stood with Gingrich. Combined with the "no" votes from some liberals, that was just enough to sink the deal, briefly shut down the government, and hand Bush a humiliating political defeat.

At first, there was talk that Gingrich had overreached -- that the fallout from the botched deal (which included a new compromise package that was more friendly to Democratic demands and hiked tax rates on higher-income earners) would cause many of his allies to turn on him, with an assist from the White House and top congressional Republicans. Public attacks on Gingrich from prominent Republicans followed, as well as private efforts to kneecap him by ousting his ally, Rep. Guy Vander Jagt, as the head of the GOP's House campaign committee.

''You pay a penalty for leadership,'' Dole remarked. ''If you don't want to pay the penalty, maybe you ought to find some other line of work.''

The uproar seemed to wound Gingrich in his Georgia district, where in the November '90 midterms he was nearly unseated by his Democratic challenger, a man who had no money, no name recognition and no support from his national party. But leaders of the conservative movement had Gingrich's back. The heads of more than a dozen groups on the right signed a letter praising the revolt he led, while voices on talk radio -- which was then emerging as a major opinion-shaping force within the GOP -- hailed him as a hero. When Gingrich returned to Washington after his close call back home, his position had actually been enhanced. The real effect of his rebellion had been to clarify the difference for conservatives across the country between the style embodied by Bush and the rest of the old guard and that of Gingrich and his acolytes.

From that point, it was only a matter of time before Gingrich supplanted Michel as the top House Republican. Sensing that the aging Illinoisan was nearing the end of the line anyway, Gingrich declined to challenge him after the 1992 election, and less than a year later Michel announced that he'd retire after the 1994 midterms. There was no race to succeed him: Gingrich already had the votes, and when Americans then handed the GOP control of the chamber, he was in line for the speaker's gavel.

The situation is not perfectly analogous now, if only because there isn't such an obvious moderate/conservative divide in today's GOP. The split that exists now is driven more by the base's distrust of perceived insiders -- those Republican leaders who (in the right's view) compromised their ideological principles over the last decade, abetted the Bush 43 mess, and enabled Barack Obama's rise. This feeling is best captured by the Tea Party movement, which accounts for the heart of Gingrich's support. So if Gingrich can convince the party's base to treat the attacks on him as a product of the GOP's sellout class and its desire to nominate Romney, he could essentially replicate his '90 breakthrough.

Some of his critics are making this easy for him. CNN's "State of the Union" on Sunday, for instance, was a virtual reenactment of the '90 drama, with Sununu -- now a Romney backer -- bashing Gingrich while former Pennsylvania Rep. Bob Walker, one of Gingrich's chief lieutenants in '90, fought back. Or there's Alan Simpson, the No. 2 Republican in the Senate 21 years ago, who was referring to that budget battle when he said recently that Gingrich “lied to the president of the United States’’ and vowed that “I am ready to tell that story around the United States."

Plus, he's getting an assist from Rush Limbaugh -- just like he did during the budget battle 21 years ago. Limbaugh has been pleading with his millions of listeners to ignore the Republican attacks on Gingrich, arguing that they aren't coming from voices that deserve to be trusted:

The conservative movement, and I mean this from bottom of my large beating heart -- ba-boom, ba-boom, ba-boom -- the conservative movement is made up of me, talk radio, the Tea Party and the American people who are conservative. A conservative movement made up of movement media people, there hasn't been that since Mr. Buckley passed away.

What may complicate this effort is that some of those sounding the alarm over Gingrich -- like Sen. Tom Coburn, for instance -- have seemingly impeccable conservative credentials. Whether enough of them speak up -- and do so forcefully and persistently enough -- may determine whether Gingrich is once again able to use his intraparty critics as a tool for political advancement.

Shares