There is no way to deny that on NPR today, author Caitlin Flanagan tried to lecture me on how I might have had a "better" adolescence. (There is proof on the Internet, so I know I didn't hallucinate it.) Specifically, she tried to use me as an example of the perils of having the Internet in your room as an adolescent, because I didn't happen to meet a great guy to date in high school. The remedy? More princess movies.

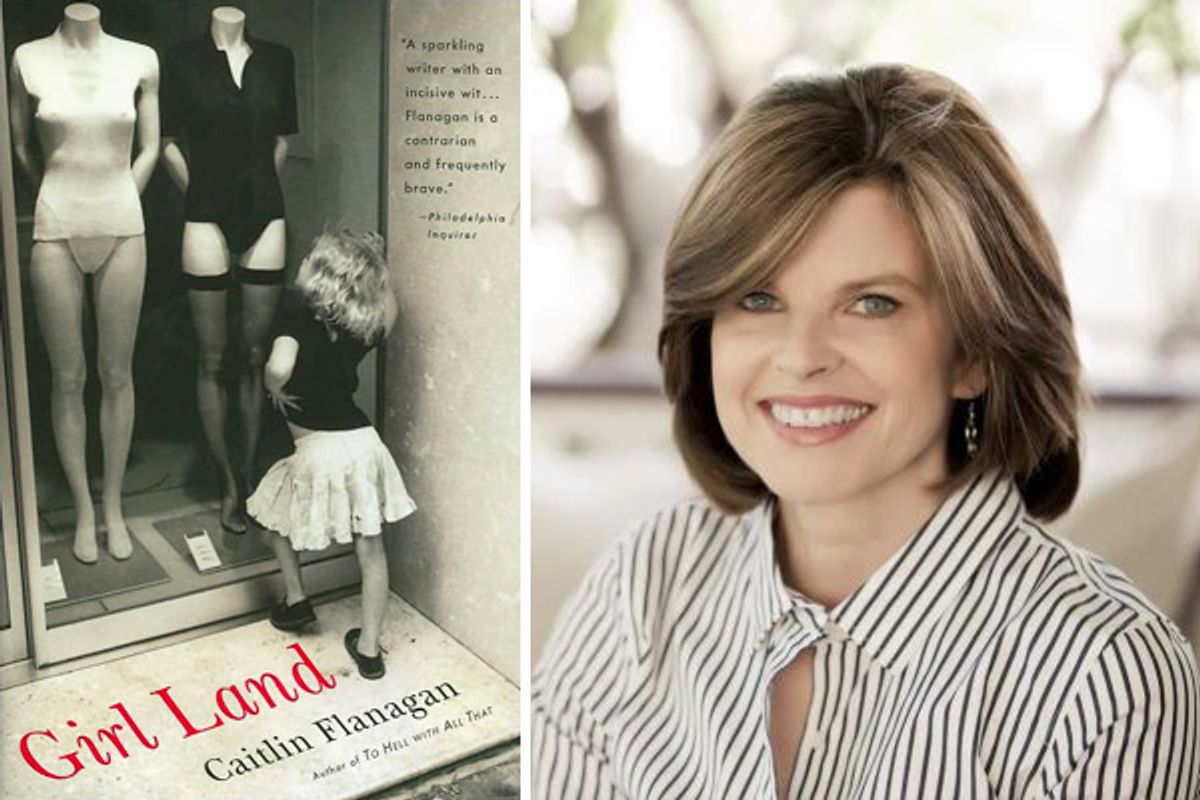

Many people, including my actual parents, think I turned out pretty OK. And Flanagan, whose book "Girl Land" I reviewed here, usually restricts her professional vocation of annoying feminists to print. So what was I doing defending my very existence on the radio?

"Do you know about Quakers? They try to find the good in everyone, and I felt you tried to do that in Flanagan's book," the producer at NPR's "On Point" told me, as he tried to convince me to take part in the on-air discussion. (If you read my review, you'll see this says more about the laceration Flanagan received elsewhere than any unusual empathy on my part.) I told him I was reluctant to engage in something that could turn into a catfight, but was persuaded that the thoughtful tone of the show and its host would prevail. Ultimately, too, I didn't want to shy away from a fight that I thought was important.

My other worry was that Flanagan would use the first half-hour, which she had exclusively to herself, to moderate her message and preempt any criticism, leaving me to lamely disagree. Others had also seen her analysis as dangerously nostalgic, a fantasy of sheltering precious girls that seemed divorced from real girls' lives and totally ignored the lives of boys. Turns out I needn't have worried.

After all, this is a major component of what people pay her for: Trolling, plain and simple, a Michele Bachmann-esque disregard for facts, only better-read and better-written. What could possibly induce her to stop?

On the air, she went even further, by suggesting several times that women and girls are solely responsible for whether men treat them like princesses (as one caller said she suggested to her daughter while watching princess movies, which Flanagan cheered) or like sluts, and whether those men stick around to parent, too. When the host, Tom Ashbrook, politely accused her of setting up a false dichotomy between parents who cared about their daughters in the culture and those who didn't, she replied, "I think there are, you know, people who are very comfortable with their daughters being part of a culture where they're servicing boys and they're even comfortable with their girls performing oral sex on boys they don't know very well. There are a lot of moms like that and I accept that."

And then she turned on me. I had first taken issue with how she seemed to demonize boys or imply that they weren't hurt by gender norms. When I talked about the need for information about safe sexuality and healthy boundaries, she responded, "I think as far as information, what I'm seeing is that girls have lots and lots of information about sexuality. I can show you lots of eighth-grade girls who know how to roll on a condoms because they've learned that in school. And I think all of that may be fine for some girls, to send them out into this pornified culture with that information, probably best that they have it." Some girls, meaning those slutty girls who will never get a man to love them! In any case, when I called her out for that bizarre conflation of porn and sex ed, she got personal.

I'd pointed out earlier that I'd had the Internet in my bedroom as a teen, something Flanagan specifically wants parents to ban. I also described my adolescence not as the dreamy withdrawal she'd described, but as "a very fertile time where I was really lucky to have a supportive community that allowed me to pursue intellectual and creative pursuits."

Never mind those things. "Let me ask you a question, Irina," said Flanagan. (The host had already said my name, Irin, correctly.) "Did you have a boyfriend in high school?"

Then I made a mistake -- I answered. "I dated some guys who were probably not great guys but I was lucky that nothing really bad ..."

"What could we adults have done to you to help you with your dating relationships?" she persisted. We went to commercial before I could sputter a reply. (Nothing could have been done "to" me, and like I said, nothing really bad happened.)

Flanagan had the floor when we got back, at which point she used me as an example of a cautionary tale of how girls who are "empowered" and have Internet access allow themselves to be abused by men. Or something. "My book 'Girl Land' is asking, What could we have done differently for Irin, so that in addition to the IM and the Internet and the sex-ed classes, she also had something that would help her interact with boys where she could find a way that boys would treat her kindly?" Flanagan cooed.

Never mind that Flanagan writes in her book about a more traumatizing adolescent experience than I ever had, an assault that took place on a conventional date and without Internet in her bedroom and without "hookup culture." Was that her fault for not demanding more of men?

"Caitlin, I so much appreciate your concern for me," I replied, "but frankly, my adolescence was fine ... I think that making mistakes is part of adolescence and how you figure out how to partner with people." I also said, "I don't think this should be about me, nor should it be about you. This is really about what's going on in the American culture." (I lost that battle.)

Ashbrook asked, sensibly, "Is that the measure of a good adolescence, whether they had a good boyfriend in high school?" It wasn't of mine -- I said that for me the measure was that "I emerged feeling happy and connected and with healthy relationships, got into the college of my choice, have a career that I am happy about, where I get to debate Caitlin Flanagan about female sexuality."

I'd gone into said debate with the idea of maybe seeing the good in her, or at least seeking a thoughtful discussion of where we diverged and why. That's where I really went wrong.

Shares