Early this year, the United Methodist Church Board of Pension and Health Benefits voted to withdraw nearly $1 million in stocks from two private prison companies, the GEO Group and Corrections Corporation of America (CCA).

The decision by the largest faith-based pension fund in the United States came in response to concerns expressed last May by the church’s immigration task force and a group of national activists.

“Our board simply felt that it did not want to profit from the business of incarcerating others,” said Colette Nies, managing director of communications for the board.

“Our concern was not with how the companies manage or operate their business, but with the service that the companies offer,” Nies added. “We believe that profiting from incarceration is contrary to church values.”

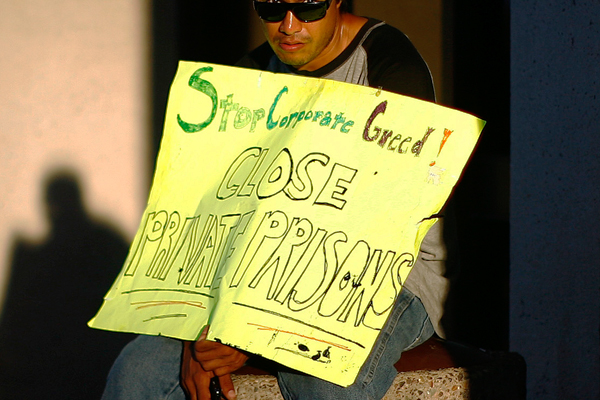

It was an important success for a slew of activists across the country who are pushing investors and institutions to divest from the private prison industry.

The National Prison Divestment Campaign, launched last spring, includes a broad coalition of immigrant rights, criminal justice and other organizations targeting private prison companies like CCA and the GEO Group, the two largest private prison corporations in the United States.

Affecting companies’ bottom lines is just one of the campaigners’ aims. Their larger goal is to raise public awareness about an industry they claim not only profits from incarceration, but also drives local and national immigration and criminal justice policy.

“Divestment is a way to engage people where they are,” said Bob Libal, an organizer with Grassroots Leadership, a team of community organizers based in North Carolina and a member of the campaign. “You might not have a private prison in your community, but I bet you have a Wells Fargo, or another institution that is invested in and buying stock in these corporations.”

“These are publicly traded corporations,” he added. “And they should be held accountable.”

16 Cities Targeted

On Jan. 24, the campaign launched events in 16 cities—including Salt Lake City and Boston—during a coordinated national day of action. Activists, including some with Occupy Miami, were arrested in Boca Raton, Fla., for protesting investors’ ties to prison companies and immigration detention centers at the GAIM hedge fund conference.

In the past year activists have staged protests at financial firms, including “occupations” of branches of Wells Fargo, which holds stock in the GEO Group. The campaign has claimed some noteworthy successes in addition to the Methodist Church decision.

Last February, Pershing Square Capital Management, a powerful hedge fund run by investor Bill Ackman, unloaded about 3.4 million shares of its stock, despite having called it an “attractive investment” in a letter to investors only two months prior.

Pershing Square had been the campaign’s first target. Pershing bought into CCA in 2009, and at one time owned 10 percent of the company, the largest share of any single investor. But the partial sell-off spurred protesters to push the company even further.

On May 12, activists protested outside Ackman’s Manhattan apartment building during a day of action that saw other protests targeting Wells Fargo, Fidelity and other firms throughout the country. Days after the protest, Ackman had sold the rest of his shares — over 4 million.

All told, Pershing divested about $200 million from the company.

Pershing did not respond to requests from the Crime Report for comment

The Pershing divestment “was shocking to us,” said Peter Cervantes-Gautschi, executive director of Enlace, a coalition of labor and community organizations in Mexico and the United States. “Not that they divested, but that they divested so quickly.”

Profit Windfall

For decades, private prison companies have been seen as solid investments by banks and hedge funds like Pershing Square.

Founded in the 1980s and fueled by the increase in mass incarceration, companies such as CCA and the GEO Group saw explosive growth through the early 1990s. As tough-on-crime measures such as mandatory minimum sentencing, truth-in-sentencing and three-strikes laws helped to pack American prisons, corrections companies saw a windfall in profits.

In the early 1980s, there were hardly any private adult prisons in the U.S. By 1990, there were 67 privately run detention facilities, with an average population of 7,000 inmates.

Proponents of private prisons argue that they provide better services for lower cost. But critics counter that privatizing detention services — in addition to being morally questionable — leads to cost-cutting measures that hurt both employees and the incarcerated.

“There’s been a lot of research that shows that private prisons haven’t delivered on their promises to provide a better product,” said Prof. Michele Deitch, a prison expert at the University of Texas.

“They have higher levels of inmate assaults on staff, inmate assaults on other inmates, higher rates of escape, and employee turnover rates are higher in private facilities,” said Deitch. “Some studies have compared recidivism rates for those coming out of private and public facilities, and have found that there’s no real difference between them.”

CCA and the GEO Group declined to comment for this story.

Prison privatization profits hit a bump in the road during the 1990s.

While incarceration rates continued to rise through the decade, many states began exploring early-release initiatives and sentencing reform to reduce incarcerated populations, leaving companies like CCA, which had built “speculative” facilities in anticipation of growing demand, saddled with debt.

They were saved, in effect, by 9/11.

In the aftermath of the terror attacks, private prisons landed profitable contracts with the U.S. Marshals, the federal Bureau of Prisons, and Immigration and Customs Enforcement, which began to expand its detention of immigrants.

“It was because of [concerns about] immigration and the uptick in federal detention contracts that they were able to survive,” said Emily Tucker, advocacy policy director of Detention Watch. “Between about 2001 and 2011, it’s been a pretty solid investment.”

And a profitable one: By 2010, GEO Group and CCA combined were posting annual revenues of nearly $3 billion.

Although financial analysts still rate the GEO Group and CCA as solid investments, they note that budget constraints and trends toward decarceration will slow growth, unless states hard push for privatization.

In 2010, according to a report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the U.S. prison population — both state and federal — declined for the first time since 1972, to slightly over 1.6 million prisoners. About 16 percent of federal prisoners, and 7 percent of state prisoners, were housed in private facilities in 2010.

“There was a time when people could bank on legislators wanting to toughen the laws and lock everyone up for a long period of time,” said Prof. Deitch. “But we’ve come to a point where we’re looking for more cost-effective approaches to dealing with our offender population. A lot of legislatures have realized that they can’t keep growing our prisons.”

Private prison companies, however, have started to explore new approaches. In an unprecedented move to gain more control of state prison systems, CCA sent letters to 48 states in February offering to purchase state prisons outright in exchange for a 20-year management contract and the assurance the prison would remain at least 90 percent full.

CCA framed its offer as a remedy for “challenging corrections budgets.”

In investor statements and annual reports, private prison companies note that immigration detention is essential to their growth. Today, private prisons — including CCA, ICE’s largest contractor — hold about 50 percent of the 30,000 people detained for immigration offenses on a given day.

Does Profit Drive Policy?

While past divestment movements tended to frame privatization as a moral issue — that privatization is wrong, in and of itself — the current campaign focuses heavily on the growth of the immigration detention industry, and how private prison companies have fueled that growth.

“It’s not necessarily that privatization is bad,” Tucker said. “It’s about the way that the profit motive influences policy.”

The passage of SB1070, Arizona’s hardline immigration bill, three years ago was the real impetus for the campaign, added Cervantes-Gautschi. Companies like CCA and GEO are prominent members of the American Legislative Exchange Council, a nonprofit that connects lawmakers and heads of industry to collaborate on state and federal legislation. Reports by NPR and In These Times exposed CCA’s involvement in the controversial law, which allows Arizona law enforcement to stop and detain anyone suspected of being an undocumented immigrant.

Similar laws have been proposed across the country and implemented, most recently, in states such as Georgia and Alabama.

“It looked to us that one piece was missing,” Cervantes-Gautschi said. “If we weren’t able to raise public interest in the role of the financial industry and those giant players in developing this private prison industry, essentially creating a market by going after immigrants, that we were never really going to win any of these fights to get justice for immigrant communities and workers.”

A number of organizations have coalesced around the divestment campaign, including branches of the Occupy movement and unions representing prison guards and employees. Cervantes-Gautschi notes that the campaign is supported by the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees.

He concedes that prison guards don’t necessarily share some of the larger prison reform goals of the campaigners.

“We don’t have precisely the same strategy, you might say, or the same solution to the problem,” he said. “But the reason there’s a growing number of people behind bars is because of these profiteering companies. On this point we’re in agreement, and we’re able to pull together.”

Organizers say one of the key factors in the campaign’s success is the participation of immigrant rights groups.

“There’s an increasing awareness of the role that private prisons are playing in immigration detention,” said Libal of Grassroots Leadership. “Legislation like SB1070 has firmly put private prisons on the map of the immigrant rights movement.”

Limitations of the Campaign

Globally, activists have used divestment campaigns as a way to raise public awareness, perhaps most notably during the struggle to end apartheid in the 1980s.

But the tactic, some point out, has limitations.

“When you sell something, you have somebody buying it,” said Alex Friedman, associate editor of Prison Legal News, a monthly magazine focusing on prison and human rights. Prison Legal News is also a partner in the campaign.

“You’re simply doing a lateral transfer of stock from one owner to another,” said Friedman. “From an activist standpoint, that’s a limited utility.”

Private prisons, Friedman added, are also a difficult industry to protest.

“Nobody can really boycott private prisons,” he said. “You don’t go to a grocery store and buy private prison beds.”

But targeting “brick and mortar” institutions, such as Wells Fargo, can be effective, he said — not only in making private prison stock be unattractive to companies, but also in raising public awareness.

There have been other divestment campaigns against the prison industry. In the late 1990s, the student-led “Not With Our Money” campaign targeted the Paris-based food service company, Sodexho Alliance.

Sodexho, which provided food service for CCA, was also once its largest shareholder.

Students and other activists, citing record incarceration numbers and the rise of the American prison-industrial complex, protested Sodexho on university campuses where the company held contracts. Students held campus sit-ins and dining hall boycotts at universities across the country, garnering media attention in major outlets such as The New York Times.

In 2001, Sodexho divested from CCA.

“’Not With Our Money’ was very successful because it provided people with a highly recognizable target that they could see and interact with,” Friedman recalled. “Students could see it every day when they went to the dining hall for breakfast, lunch and dinner.”

“Wells Fargo has branches people can protest in front of,” he added. “They are susceptible to bad publicity. If you have one of two banks you want to put your money into, and one has a bunch of protesters outside waving signs, you’re more liable to put your money somewhere else.”

It’s the raising of awareness, according to Cervantes-Gautschi, that may be most important.

“We took a chance on the strategy during the anti-apartheid movement,” he said. “But part of what the divestment strategy accomplished was educating a lot of people about apartheid, and how much our own government and our own institutions were invested in it.”

“The more that became public, the more people said no,” he added. “It’s not about divesting money; it’s about divesting our relationships.”