When I was 10, I showed up at the breakfast table one morning with the sandpapery scabs of an experiment-gone-wrong on my face. I’d tried to engineer rosy cheeks by scouring with a wash cloth, thinking it might buff my olive coloring toward a more Norman Rockwell hue.

When he saw what I’d done, and realized it was no accident, my dad nearly spewed his 40 Percent Bran and demanded an explanation.

When he saw what I’d done, and realized it was no accident, my dad nearly spewed his 40 Percent Bran and demanded an explanation.

I told him I didn’t want to look “Mexican.”

The borders of legitimacy were quite clear for a 10-year-old: Looking Mexican was not desirable.

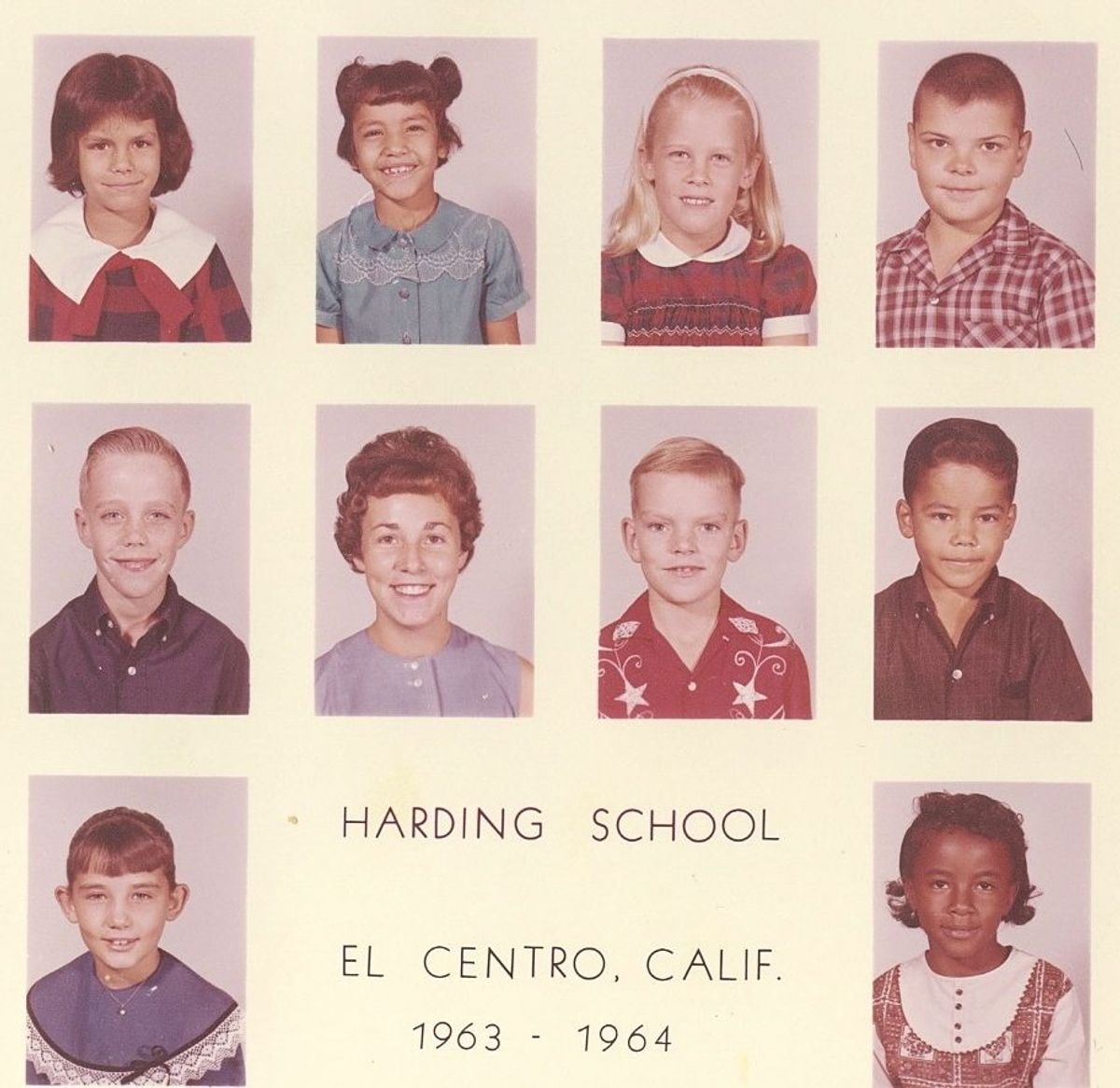

In the 1960s, in our small California border town, there was no distinction between Mexican and Mexican-American – and the word “Mexican” was sometimes considered a pejorative. One public official I knew referred to a “Spanish gentleman” rather than call him Mexican.

My olive-colored skin and foreign-sounding last name were a double whammy where most of the Manuels and Marias, Javiers and Julias were poor, Spanish-speaking, and segregated into lower-level classes. The borders of legitimacy were quite clear for a 10-year-old: Looking Mexican was not desirable.

White teachers, I felt, sometimes treated me “like a Mexican.” Once, new to a school, I was tracked into remedial-level classes, largely full of migrant “Mexican” kids with poor English skills. Mexicans would treat me “like a Mexican” by simply speaking Spanish to me. Even a close girlfriend enjoyed needling me condescendingly: “Face it, you’re brown, not Caucasian. But skin color doesn’t matter.”

My dad offered no moralizing and just laid down his law. He said women envy dark hair and healthy tans – so get over it. Never mind that my dad had done some scouring of his own. A child of immigrants, he spoke only Italian until first grade and then embarked on a lifelong linguistic-cleansing program that included getting rid of his accent, going to radio school to make his English diction perfect, and “Americanizing” the pronunciation of his last name from GerMAHni to GerMAINi.

We lived just eight miles from the Mexican border in a town called El Centro – The Center, which described its location in the Imperial Valley, but also, in a way, its location in its white residents’ world view. We rarely crossed that actual border into the dusty, impoverished streets of Mexicali – the capital of Baja California and a growing metropolis many times the size of our small town. We felt equal parts fear and disdain of the place.

Abey, a macho boy who smelled like pomade, melted my heart by calling me a beautiful “mamacita.” Dahlia braided my hair. Even if they were appealing playmates, they were “foreign.”

That border seemed to morph metaphorically northward, like a rubber band that kept the Mexican kids I knew together with palpable social tension. It was a cultural line, for sure, but it was also a border of class distinction. As a 10-year-old, I felt it personally, but – without the social or humanitarian radar to understand – I was hardly sympathetic. Even as current-events discussions at our school were informed by Martin Luther King Jr.’s struggles for racial equality, we all seemed ironically oblivious to what was happening right on the playground.

Abey, a macho boy who smelled like pomade, melted my heart by calling me a beautiful “mamacita.” Dahlia, who badly wanted to be in the Brownies but was actively discouraged by the den mother, sat behind me in class and braided my hair. Blushing-shy Modesto was one of the sweetest boys I’d ever met. But outside school, our paths never crossed. Even if they were appealing playmates, they were “foreign;” their brown lunch bags smelled like corn tortillas, not Wonder-mayo-tuna sponges; their moms weren’t in the PTA; and sometimes their dads would pick them up from school and load them in the back of banged-up pickups.

They defined “Mexican” for me – mysterious, somehow sadly off-putting, and different. I didn’t want to be them.

The stain of ignorance was embarrassing as I grew up and out. I attended a university in Los Angeles full of Hispanic valedictorians and other strivers. I went on to learn – and mangle – Spanish as an adult. And I was blessed to be assigned newspaper reporting assignments all over Latin America, discovering a vast and intriguing expanse of people, cultures, and geographic borders between El Paso and Patagonia – a region that had been all vaguely “Mexican” to me as a child.

I only became confident of my personal border reform when in the 1990s, I was being considered for a job at a metropolitan newspaper and the hiring editor reached the end of the interview and his political correctness: He asked me if there was anything to my dark skin and hair that might help my application: They needed a minority hire.

“Like, am I Mexican?” I asked. He gave a discreet – uncomfortable – eyebrow twitch to confirm.

Then I added, “I wish.”

And I meant it.

Shares