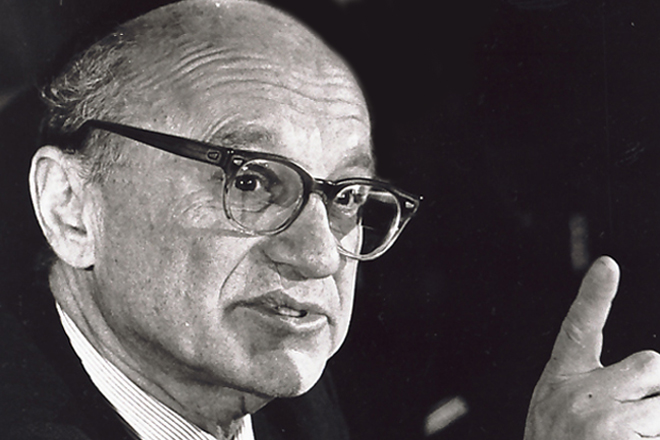

July 31 would have been the 100th birthday of the economist Milton Friedman, who died in 2006. The centenary of his birth was celebrated by libertarians and anti-statist conservatives. But it should have been celebrated by progressives as well as centrists and the remaining moderate conservatives in America. Without intending to, Milton Friedman helped his adversaries in two ways. He undercut any principled opposition by the right to the expansion of the welfare state. And he inadvertently strengthened the case for the existing system of welfare and social insurance by devising elaborate alternatives that proved to be deeply unpopular with the American people.

The lasting legacy of the famous University of Chicago economist in the realm of public policy is his design for an alternative welfare state that could be embraced by libertarians and conservatives. (For his part, Friedman described himself as a “classical liberal.”)

The alternative welfare state that Friedman proposed had two parts. For the bottom tier of the alternative welfare state, Friedman proposed using a negative income tax (NIT) to replace most or all means-tested welfare programs, including in-kind benefits like food stamps and public housing. The negative income tax would be a refundable tax credit — that is, individuals too poor to pay federal income taxes would receive a check in the amount of the credit from the IRS.

The rest of the Friedmanite welfare state was to have consisted of vouchers paid for out of tax revenues in amounts designated by the government for particular purposes designated by the government. Friedman proposed replacing the public school system with vouchers that parents could spend on private schools of their choice. In healthcare, Friedman proposed a system of vouchers, combined with an individual mandate to buy catastrophic health insurance from the private sector. And Friedman’s influence was behind the decades-old campaign of the right to privatize Social Security, replacing it with a system of mandatory investment by individuals in tax-favored private savings accounts like 401Ks and IRAs.

Ideas for voucherizing public schools, voucherizing healthcare and voucherizing Social Security have dominated discussions of reform for the last half-century — not because they are popular, but because a few right-wing billionaires like the Koch brothers have poured money into libertarian propaganda mills disguised as think tanks like the Cato Institute, the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and the Heritage Foundation (where I worked briefly in my misspent conservative youth). Notwithstanding the vast sums invested by the plutocrats of the right to popularize Friedman’s ideas, every element of the Friedmanite welfare state has been rejected by the American public.

The negative income tax was the first to be rejected. Supported in the early 1970s by a coalition of libertarian conservatives and progressive supporters of a “basic income,” proposals for a negative income tax never made it through Congress. Then and now, the American people did not like the idea of paying able-bodied, sane adults a minimal income, whether they work or not.

The earned income tax credit (EITC), a wage subsidy for low-wage workers, is sometimes treated as a version of the NIT and a triumph for Milton Friedman’s approach. It is nothing of the kind. The fact that it is administered through the tax code, as the NIT would have been, is not significant. The EITC was created and has been repeatedly expanded precisely because it is an alternative to the kind of basic income supported by Milton Friedman and rejected by the American public.

The American people have also rejected the schemes of Friedman and his disciples to replace popular middle-class programs with voucher schemes. Half a century of advocacy of public school choice, by libertarians, including billionaires like the late Ted Forstmann, along with religious fundamentalists who want taxpayer money for their sectarian schools, have shown no results, other than minor experiments with charter schools within public K-12 systems.

The politics of school choice have been paradoxical. The most problem-plagued public schools tend to be in poor inner cities, whose voters are disproportionately black or Latino and Democratic, while the best public schools are those in the affluent suburbs, which in much of the U.S. tend to be Republican. The right-wing proponents of school choice have repeatedly been defeated, in state and local campaigns, by the satisfaction of suburban Republicans with their neighborhood public schools.

Social Security privatization has also been a colossal flop. Following his reelection in 2006, President George W. Bush pushed for optional, voluntary partial diversion of Social Security payroll taxes to private retirement savings accounts. Never had the stars been more favorably aligned for a Friedmanite proposal. The Republican Party controlled the White House, both houses of Congress and the Supreme Court, and partial privatization was supported by many neoliberal “New Democrats.” But the proposal to voucherize Social Security was so unpopular with Republican voters, as well as Democrats and independents, that no legislation was ever debated in either house of Congress under Republican control.

Some on the right still dream of voucherizing Medicare. If history is any guide, the voters and their representatives in Congress will say no.

The only exception to the perfect record of failure of Milton Friedman’s policy proposals is the Affordable Care Act of 2009 — “Obamacare.” In essence, the individual mandate portion of ACA is a version of Milton Friedman’s proposal, backed by the Reagan administration in the 1980s, to force Americans to buy catastrophic health insurance.

Although the Supreme Court recently upheld the constitutionality of the ACA, it remains to be seen whether the individual mandate to buy insurance, through a complicated system of state “exchanges,” will succeed. If the overly elaborate scheme fails and is eventually scrapped for something simpler, more efficient and less costly, Milton Friedman’s record as a proponent of welfare state and educational reform will be unblemished by a single success.

Although Friedman’s alternative to the modern welfare state has not met the test of public approval and legislative enactment, the late economist unwittingly performed an invaluable service to the center and the left. He accepted the legitimacy of public sector guarantees of minimal income for the poor, universal access to education and universal access to adequate healthcare and retirement income security.

Milton Friedman took for granted the legitimacy of the welfare state, in both of its forms — means-tested public assistance for the poor and universal, middle-class social insurance. He believed it was utopian for his fellow libertarians to propose abolishing public assistance and middle-class social insurance programs outright. That is why he proposed the negative income tax, as a substitute for other means-tested programs for the poor. And it is why he proposed voucherizing universal, middle-class social insurance programs like Social Security and Medicare, along with public K-12 education.

But as ultra-liberarians have periodically complained, that meant that Friedman supported big government. After all, the negative income tax is government welfare in its purest form — the government writes a check to citizens, whether they work or not. Likewise, a voucher program is just as much a government program as direct public provision of a good or service.

While those who receive the voucher may have a choice among vouchers, every other aspect of a voucher program is “big government” in its purest form. The government raises the taxes to pay for the program and redistributes the money on the basis of need. The government, not the market, determines the amount of the voucher. The government, not the individual, determines the purposes for which the voucher can be spent. And the government certifies only certain providers as eligible for receiving the tax-based voucher money. With good reason, more principled libertarians object to voucher schemes as “voucher socialism.”

Voucher schemes do not replace “bureaucracy” with “markets.” They merely replace a single public provider — a public K-12 system, say — with a handful of government contractors in a phony, rigged market created by government.

Nor do voucher schemes necessarily reduce government bureaucracy. On the contrary, they may require government to hire new bureaucrats, in order to supervise both the recipients of vouchers and the voucher-funded government contractors, to prevent them from gaming the complicated system.

The ultra-libertarians are right. Milton Friedman engaged in unilateral intellectual surrender to the supporters of a large, generous modern welfare state. He accepted the legitimacy of a welfare state in principle, and merely sought to substitute other government programs, with limited choice among certified government contractors, for existing government monopolies. His schemes have all been so unpopular that they have never been tried on a large scale, with the sole exception of the individual mandate part of the Affordable Care Act, which is likely to fail in practice.

Milton Friedman’s unintended service to supporters of modern government did not end with his acceptance of the legitimacy of the welfare state. Friedman also proposed the most thoughtful alternatives to the modern welfare state that anybody on the right has ever come up with or is likely to come up with in the future. This was a useful intellectual and political exercise. The fact that the alternative welfare state has been rejected by the public, and probably would not work even if it were tried, greatly strengthens the case for modifying the inherited welfare system, rather than scrapping it entirely for a radically different design.

As if those services had not been enough to make him a hero of big government, Milton Friedman’s proposals for tax reform also blazed a trail that 21st century architects of adequately scaled government can follow.

In his 1943 article “The Spendings Tax as a Wartime Fiscal Measure,” Friedman proposed a new federal tax: a progressive consumption tax. A progressive consumption tax is calculated by subtracting savings from income, and treating what remains as consumption to be taxed. A consumption tax can be made progressive, by exempting a certain amount of consumption from taxation.

Many economists across the political spectrum have supported a progressive consumption tax. But in the only two countries in which it was tried, in India and Sri Lanka, tax revolts quickly led to its abolition. Governments prefer indirect consumption taxes like sales taxes, which, unlike a progressive consumption tax, are not collected all at once, and are therefore less likely to create “sticker shock” among taxpayers once a year.

All developed countries other than the U.S. use a value-added tax, which has the merits of a sales tax (it is indirect) while avoiding its defects (cascading taxes). A value-added tax with a rebate to make it less regressive is the functional equivalent of Milton Friedman’s progressive consumption tax. The conservatives who denounce proposals for a VAT in the U.S. logically should also denounce the progressive consumption tax supported by Friedman. And progressives who propose to reduce long-term deficits and finance an expansion of necessary government services in part with a federal VAT, as the social democracies of Northern Europe do, can invoke the reasoning of the patron saint of the Chicago School of Economics.

Happy birthday, Professor Friedman. You didn’t know it, but you were inadvertently helping to make the case for the modern welfare state all along.