In 1947, my father, screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee in Washington, D.C. He, along with nine other writers, directors and producers, who became known as the Hollywood Ten, refused to answer questions about his political associations, and he was later convicted of contempt of Congress and served 10 months in a federal prison. We lived in Mexico City for two years, and following our return to Los Angeles in 1954, my father scrambled for work to support his family, writing screenplays under assumed names and behind fronts, for fees well below his pre-blacklist salaries. He hoped to find a way to use the black market to undermine the Hollywood blacklist, which had destroyed so many careers and lives. His goal was partially achieved in 1960 when his name, Dalton Trumbo, appeared on the screen for the first time in 13 years, on not one, but two films — “Exodus” and “Spartacus.” For my father, the blacklist was over. But for countless others, it was not.

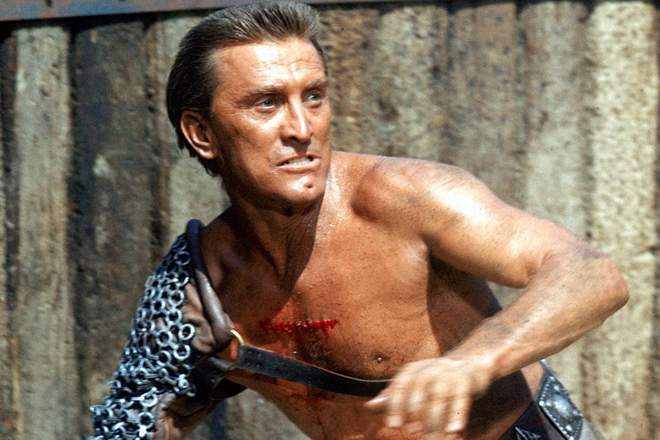

In Kirk Douglas’s new book, “I Am Spartacus!,” which has received much recent media attention, this small piece of history has been distorted. For years Douglas has claimed to have single-handedly broken the blacklist — he has accepted awards, written books and given speeches. Last December, in a letter to the New York Times, Douglas stated, “In 1959, when I broke the blacklist and gave Dalton Trumbo screen credit for writing ‘Spartacus,’ it was one of the proudest decisions of my life.” In his book, Douglas has not only inflated his role, but there are incidents that did not happen: For instance, my father did not have lunch with him at the Universal studio commissary, did not disguise himself to attend a screening, and Laurence Olivier did not have dinner at our house. He has also asserted a brand-new claim — that he, not my father, wrote the iconic “I am Spartacus” scene from the film.

The “Spartacus” back story is more complex than Douglas’ account. In 1959, Trumbo was under contract to Bryna, Douglas’ production company, writing “Lonely Are the Brave” (which would be released in 1962), using the name Sam Jackson. Producer Eddie Lewis, who had hired him, asked my father to switch his efforts to “Spartacus.” Lewis needed a swift revision of the script, and he knew that my father was fast and good. His hiring became an open secret in Hollywood when Anthony Mann, the director, brought Peter Ustinov to our house in Highland Park for consultations. After the “Spartacus” script had been completed, with many rewrites along the way, Otto Preminger came to Trumbo with another problematic script, “Exodus.” My father and Preminger spent all of December 1959, and much of January 1960, writing and conferring 12 hours each day, including Christmas. Preminger became a fixture at our house.

My father, of course, wanted screen credit on both these films. He had been laying the groundwork since 1957, when “Robert Rich,” one of his pseudonyms, won the Oscar for best screen story for “The Brave One.” When no Robert Rich could be found, my father leveraged the fiasco brilliantly, spreading the idea that the blacklist wasn’t working — that blacklisted writers were, indeed, writing films, and that perhaps all recent films of any merit had actually been written by blacklistees. In January 1959, both Trumbo and the King Brothers, the producers of “The Brave One,” announced that Trumbo had written the film. By then, anyone who read the trades knew that blacklisted writers had written “The Defiant Ones,” “Inherit the Wind,” “Bridge Over the River Kwai” and “Lawrence of Arabia.” The American Legion, the Motion Picture Association of America, the major studios, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences all became embroiled in the drama.

Ring Lardner Jr., one of the Hollywood Ten, said it well in a New York Times article from 1982:

A decisive factor in the ultimate collapse of that evil system was a campaign initiated and orchestrated by Dalton Trumbo that employed ridicule as a major means of demonstrating how unfair and contrary to American democratic principle the blacklist was. He saw to it the media were made aware of every contradiction in the process, especially every time an Oscar or some other distinction was awarded to a pseudonym, and when prominent movies were attributed to him, he refused to confirm or deny his authorship. Finally, even the executives who had instituted the blacklist came to see how foolish and disruptive it was.

In early 1960 it was clear that neither Douglas nor Lewis could guarantee my father a credit on “Spartacus”; it was a decision that had to be approved by Universal Studios, and the studio executives were extremely cautious. Otto Preminger, however, did not need the approval of his distributor, United Artists, to put the name Dalton Trumbo on “Exodus.” When Preminger announced that he was putting Trumbo’s name on the film, it was groundbreaking.

My brother Chris Trumbo described the sequence of events:

On Jan. 20, 1960, the New York Times carried the story that Otto Preminger had hired Dalton Trumbo to write the script for “Exodus,” and that he would start shooting in April. On August 8 of the same year Kirk Douglas announced in Variety that Trumbo had written the script for “Spartacus” … Both pictures opened in the winter of 1960. Finally, my father’s name was seen again on the American screen — without having cooperated with the Committee, without naming names, without recanting previously held beliefs.

Thirty years later, in 1991, the Writers Guild of America invited my mother, Cleo, to attend its annual awards dinner, where the Robert F. Meltzer Award was to be presented to Kirk Douglas for his role in Trumbo’s screen credit for “Spartacus.” Cleo wrote back: “It is important to remember that it was Otto Preminger who first announced that Dalton Trumbo’s name would appear on his film, “Exodus” … This observation is not meant to diminish Mr. Douglas’ actions, for what he did required courage, but merely to put them in perspective … It is rarely, and only after deep consideration, that I presume to speak for my husband, but I am certain, if he were still living, that he would think it unconscionable that Otto Preminger would be ignored and only Kirk Douglas honored by the Guild for his contribution in helping to destroy the blacklist. I am also certain that he would not attend a ceremony which sanctioned such a distortion of the actual events.” The award was presented to Mr. Douglas alone, as planned, and my mother did not attend.

Years later, in 2002, in another attempt to bring the facts to light, my mother wrote to the Los Angeles Times:

While it took men of principle and courage like Preminger and Douglas to at long last defy the Hollywood studios, it is my unwavering conviction that it was primarily the efforts of blacklisted writers themselves that caused the blacklist to be broken. For more than 12 years these men and women continued to write without credit at a fraction of what they had earned before. For more than a decade they brought lawsuits, gave speeches, wrote articles, published pamphlets, and pleaded their cause on television and radio. By the time Trumbo’s name appeared on “Spartacus” and “Exodus” the ground had been well prepared by the ceaseless efforts of blacklisted writers.

In the preface to his play about our father, “Red White and Blacklisted,” my brother stated that Trumbo never claimed to have broken the blacklist. No one person did. “When Trumbo’s name appeared on the screen again with the release of ‘Exodus’ and ‘Spartacus’ in 1960, there were some who credited Trumbo with ‘breaking the blacklist,’ although he certainly never claimed to have done so, notwithstanding his decade-long dedication to destroying it. Others, producers Frank King and Kirk Douglas come to mind, claimed the distinction of breaking the blacklist. They didn’t break it, either. The demise of the blacklist was slow, like a giant balloon in a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade which has sprung a leak and finally collapsed. As in T. S. Eliot’s vision of the world, the blacklist ended not with a bang, but a whimper.”