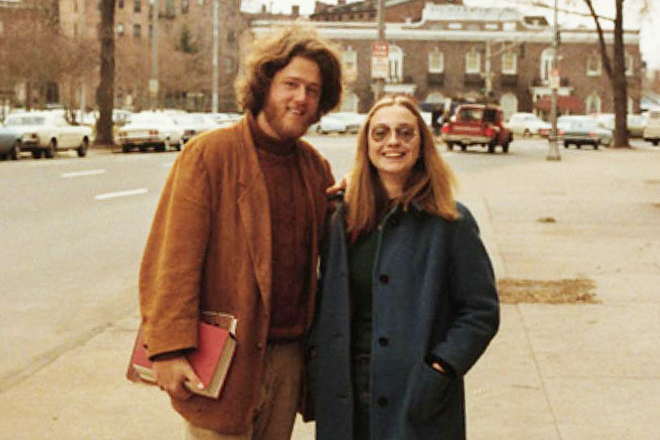

When Bill Clinton arrived at Yale in the fall of 1970, one thing was clear: Politics would be the singular focus of his life. Far less clear were his other priorities. He continued to exude charm and affability, drawing to himself potential political allies, personal friends, and devoted acolytes. But what about his intellectual life? Did academics matter? Should he prepare for a professional career if politics did not work out? More important, would he be able to reconcile his parallel lives? In particular, how would he resolve his persistent inability to sustain a long-term relationship with a woman? Repeatedly, he had commented on his lack of commitment to others. His relationship with Ann Markusen—whom he first started to date at Georgetown—had broken off, even though he said he loved her, because he could not bring himself to say yes to a long-term relationship. It was a story repeated again and again, throughout his stay in England and now on his return. Instead of sustained commitments, he had begun a chronic pattern of carrying on multiple relationships marked by no honest communication with the various women involved. Where would all that lead?

At Yale, Clinton found an answer—another person, equally bright, just as driven to break barriers and change the world. She was almost as complicated as he was—perhaps even more so—with a family history that came close to his in its crazy dynamics. Hillary Rodham would change his life. He would change hers. And from the moment of their meeting, they created a partnership, both political and personal, that helped shape the course of the country.

* * *

There are multiple stories about how the two met. The classic version, told repeatedly, is that they had noticed each other early on. She was in her second year, he in his first. But rather than start a conversation, they circled each other warily, each sizing the other up. Then one day in the library, after Bill kept gazing at Hillary down at the other end of the Gothic-arched room, Hillary strode up to him and said, in effect, “Look, if we’re going to spend all this time staring at each other, we should at least get to know who the other is.”And the rest, supposedly, is history.

Robert Reich claims to have introduced the two at the beginning of the semester. But nothing happened. In Bill Clinton’s memoir, he says that he saw Hillary for the first time in a class on political and civil rights. “She had thick dark blond hair,” he wrote, “and wore eyeglasses and no makeup. But she conveyed a sense of strength and self-possession I had rarely seen in anyone, man or woman.” Still another version has Bill following Hillary around campus. At the time, she was still dating David Rupert. He caught up with her on her way to registration and joined her in the line, even though he had already registered. Then the two went off and talked their way into the Yale Art Museum, which was closed, but which had a special exhibit on Mark Rothko that they both wanted to see. In this story, according to Bill’s memoir, she sat down in the lap of a Henry Moore sculpture, and he sat beside her. “Before long,” he wrote, “I leaned over and put my head on her shoulder. It was our first date.”

Whatever the sequence, a spark had been struck. Clinton phoned Hillary soon after the museum experience and discovered she was sick. Immediately, and unbidden, he went to her house with orange juice and chicken soup. Clinton’s courtship had commenced. Electricity was in the air.

Clinton, a friend of Hillary’s said, was “the wild card in her well-ordered cerebral existence.” She had charted a well-organized campaign to achieve her ends in her own way, and now a new and powerful presence was scrambling her best-laid plans.

“He was the first man I’d met,” she told one interviewer, “who wasn’t afraid of me.”

For someone whose head had always ruled her heart, a new element had entered the equation. She admired his brains and his commitment, but also his physicality. In her memoir, she talks about the “shape of his hands. His wrists are narrow and his fingers tapered and deft, like those of a pianist or a surgeon.” Clinton marshaled all his resources to keep his advantage. He lobbied his housemates to “make nice” to Hillary. If they could impress her, she might think better of him. “I’d never seen anyone with that much focus,” Nancy Bekavac said. Hillary was deeply impressed by how much he cared about his origins and how much he was committed to going back to Arkansas to make a difference. Although he did not say it, she and all her friends quickly got the message about the ultimate potential of Bill Clinton. More than twenty years before it happened, they were already talking about his becoming president of the United States. “Absolutely,” Bekavac said. “I don’t think I knew him two hours before it dawned on me.” In addition to his intellectual and physical attractiveness, Clinton’s charisma clearly made an impact as well.

Bill and Hillary brought out the best in each other. She helped impart discipline and rigor into his quest for making a difference. He helped soften and humanize her. “He saw the side of her that liked spontaneity and laughter,” her friend Sara Ehrman noted. “He found her guttural laugh [appealing]: it’s fabulous—there’s nothing held back. The public never sees that side of her. When she’s laughing, that’s when she’s free.”

They also learned how effectively they could complement each other. Bill was gentle, affable, averse to conflict, and loath to attack people. Hillary was tough, direct, willing to fight and take the battle to the other side. “Clinton had the charm and sex appeal,” their friend Steve Cohen said, “whereas Hillary … was straightforward, articulate and self-possessed.” Sometimes the contrasts led to exchanges that were humorous as well as telling. “They were funny together,” Clinton’s roommate Don Pogue recalled. “Hillary would not take any of Bill’s soft stories, his southern boy stuff. She would just puncture it, even while showing real affection. She’d say, ‘Spit it out, Clinton!’ or ‘Get to the point, will you, Bill!’” Nowhere were the differences, or complementarities, more evident than when the two served as co-counsel in the Prize Trial, held before the entire law school, with opposing sets of law students trying to win a case before a distinguished judge, in this in- stance the former Supreme Court justice Abe Fortas. While Bill sought to win over the judge and jury with his charm—and brooded when their side lost a difficult procedural ruling—Hillary was all business. As Nancy Bekavac noted, “Hillary was very sharp and Chicago, and Bill was very To Kill a Mockingbird.” Stated another way, to Bill’s soft, stereotypically “feminine” qualities, Hillary brought tough, classically “masculine” traits.

The only problem was that more often than not, their complementary differences also generated outright conflict. Just as often as the two cooed and flirted, they fought viciously, using their superintelligence to rip each other apart. Neither was weak-willed, but given their other qualities—his affability and charm, her assertiveness and strong-mindedness—she was more likely to go on the attack, and he was more likely to be on the defensive. And more often than not, in a confrontation, she would be the victor and he would have to pay the price.

Nevertheless, the attraction was sufficiently strong that from that semester forward, Bill Clinton and Hillary Rodham were inextricably linked. “She was in my face from the start,” Bill Clinton recalled, “and, before I knew it, in my heart.” Hillary, in turn, remembered that “falling in love with Bill Clinton” was the most exciting thing to happen to her in the 1970s. For Bill, Hillary was something different. Other women had embodied some of what he now found with Hillary. His lifelong friendship with Carolyn Staley was always more substantive than romantic. For three years, he combined romance and friendship in his relationship with Denise Hyland. But that dynamic had less of a cutting edge, fewer direct challenges. Ann Markusen at Georgetown was the closest he had come to being involved with a person like Hillary. But she was perhaps too independent, too “in his face,” too unwilling to accommodate his style and find a modus vivendi that would allow them to develop as a couple. Hillary was different. While clearly unwilling to be submissive, she was sufficiently enchanted that, arguably for the first time, she considered melding her own ambitions to change the world with those of someone else in a joint endeavor. In his memoir, Bill declared he simply liked being around Hillary “because I thought I’d never be bored with her. In the beginning I used to tell her that I would like being old with her.” An interesting perspective. Not romantic. Not impetuous. Rather, a vision over time—a long time.

Soon enough they became a couple, with Bill moving into Hillary’s limited quarters. Interested in continuing the relationship and apprehensive about losing her if they were apart, he asked if he could go with her to California in the summer of 1971. She was going there to intern with an Oakland law firm—Treuhaft, Walker and Bernstein—notorious for its left-wing political associations. It was an interesting choice, part of Hillary’s balancing act between her “conservative mind and liberal heart.” She had taken a law course with Thomas Emerson, also known for his left-of-center proclivities, and he provided the connection to the Oakland firm, two of whose partners had been Communist Party members.

In a significant gesture of faith in their future, Hillary agreed to let Bill come along. Hillary was moving in her political agenda, now much more focused on her liberal instincts. Bill had helped in that process. His activism, openness, and warmth had clearly nudged her in new directions. The fact that she was willing to entertain this level of commitment conveyed its own message. Traveling with someone to California suggested something more than a campus relationship.

Bill, too, had changed. For someone deeply disturbed by his inability to make commitments to women, Hillary had introduced a new dimension. As he wrote, she was someone he could not get out of his head. Nothing illustrated the change more than his decision to bring her into his family sphere, an act of commitment on his part that he must have known would not be smooth. When Bill’s mother came to Yale to see her son, Virginia met Hillary for the first time. It was not a successful encounter. “With no makeup, a work shirt and jeans, and bare feet coated with tar from walking on the beach at Milford,” Clinton recalled, “she might as well have been a space alien.” But at least the initial contact had now been made. Hillary reciprocated, taking Bill to Park Ridge to meet her parents. He immediately bonded with her mother, Dorothy, while making no connection at all with her father, Hugh.

Both continued to learn about each other that summer. “He’s more complex [than I had thought],” Hillary said, “there’s lots of layers to him … The more I see him, the more I discover new things about him.” Bill seemed to feel the same. “When the summer ended,” he later wrote, “Hillary and I were nowhere near finished with our conversation, so we decided to live together back in New Haven, a move that doubtless caused both of our families concern.” It was an interesting way to summarize their time away from Yale.

Upon their return to New Haven, the two moved into an apartment near the law school where their mutual friend Greg Craig had lived. Each carried on a busy independent life. Bill was now going to class more than before; Hillary was fully involved in her clinical work on children’s rights. But the most important event to take place that fall rocked Bill Clinton, called into question all his previous assumptions, and in the end may have played a crucial role in bonding their relationship.

It all went back to Bill’s time at Oxford and the intense and intimate relationship he had developed with Frank Aller. Shortly after he returned from California with Hillary, Bill received a phone call. Frank Aller had committed suicide.

Aller had gone back to California to face the consequences of his decision to resist the draft. He turned himself in to the authorities, prepared to go to jail. But then he failed the army physical. Suddenly, what had begun as a long journey to martyrdom and prison became a roller-coaster ride to liberation. Aller was a free man. Yet when Clinton visited him in early 1971, he reported that he still “seemed caught in the throes of a depression.” Aller was spending the year writing an autobiographical novel about the life of a draft resister. “It was an exciting but also sobering experience,” Aller wrote a friend, “as I tried to assess what the decision meant after two years of living with it and what it was likely to mean in the long run. At the end of the period when I was actively revising the second draft … I realized that I was being led toward another decision just as difficult as the first one, if not more so.” It was an ominous sign.

Brooke Shearer, a woman friend from Oxford and the partner of his Rhodes classmate Strobe Talbott, was the one who called Clinton with the news. She had been one of the last people to see Aller. On the surface, everything seemed to be rosy. The Los Angeles Times had just offered him a job as a correspondent in Southeast Asia, writing about the war he hated. Yet something did not feel right to Shearer. A few days later, Aller put a gun to his head and pulled the trigger. His friends—soulmates, really—were devastated. They had lived through the traumas of his resistance decision, providing the support he so desperately needed. And now, just as things turned right, they went horribly wrong. It seemed, his Rhodes classmate John Isaacson said, that Aller “needed the war to stay alive. He needed the external crisis to avoid the internal crisis.” Another friend, Mike Shea, believed the resistance had given him something to live for. Now there was only nothingness—and the “other decision” Aller had referred to.

Clinton was devastated. Aller and he had lived through the drama of the draft decision together. It had been Aller who told Clinton he must not choose the path of resistance because he had so much to offer as a political figure. They had pondered, struggled, explored, and finally come to resolution together. Now his closest existential partner during this struggle was gone. Clinton began once again to question his own choice, the very purpose of his existence. “I am having trouble getting my hunger back up,” he wrote Cliff Jackson, “and someday I may be spent and bitter that I let the world pass me by.” The optimist became a skeptic, the do-gooder a naysayer. Greg Craig remembered a paper Clinton wrote during this time that questioned the worth of the entire social system and condemned the life of politics as inherently corrupt. “It was … an angry, hostile period of his life,” Craig said, “consistent with what a lot of us felt.”

Writing more than three decades later, Clinton reflected further on his friend’s suicide. “As I learned on that awful day, depression crowds out rationality with a vengeance. It’s a disease that, when far advanced, is beyond the reasoned reach of spouses, children, lovers, and friends … After Frank’s death, I lost my usual optimism and my interest in courses, politics, and people.”

It was in that period of crisis that Hillary came through for him. She had lived through her own periods of self-doubt and confusion. Despite being one of the most inner-directed and self-motivated students at Wellesley, she had experienced bouts of ennui, reluctance to get out of bed in the morning, alienation from the tasks before her, and a pervasive case of the “blahs.” In February of her junior year at Wellesley, and then again for a brief period at Yale, she felt doubt about the meaning of it all and wondered whether anything could make commitment and hard work worthwhile. Now, during these darkest days with Bill Clinton, she shared that part of her inner self. “She opened herself to me,” Clinton wrote. It was almost as though he were seeing a different person, less rock-hard, straight-ahead, and singularly focused than the one he had first encountered. Her willingness to be vulnerable, to share, to reveal her most private self “only strengthened and validated my feelings for her.” And in doing so, Hillary helped remind Clinton “that what I was learning, doing, and thinking mattered.”

Excerpted from “Bill and Hillary: The Politics of the Personal” by William H. Chafe, to be published in September 2012 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright ©2012 by William H. Chafe. All rights reserved.