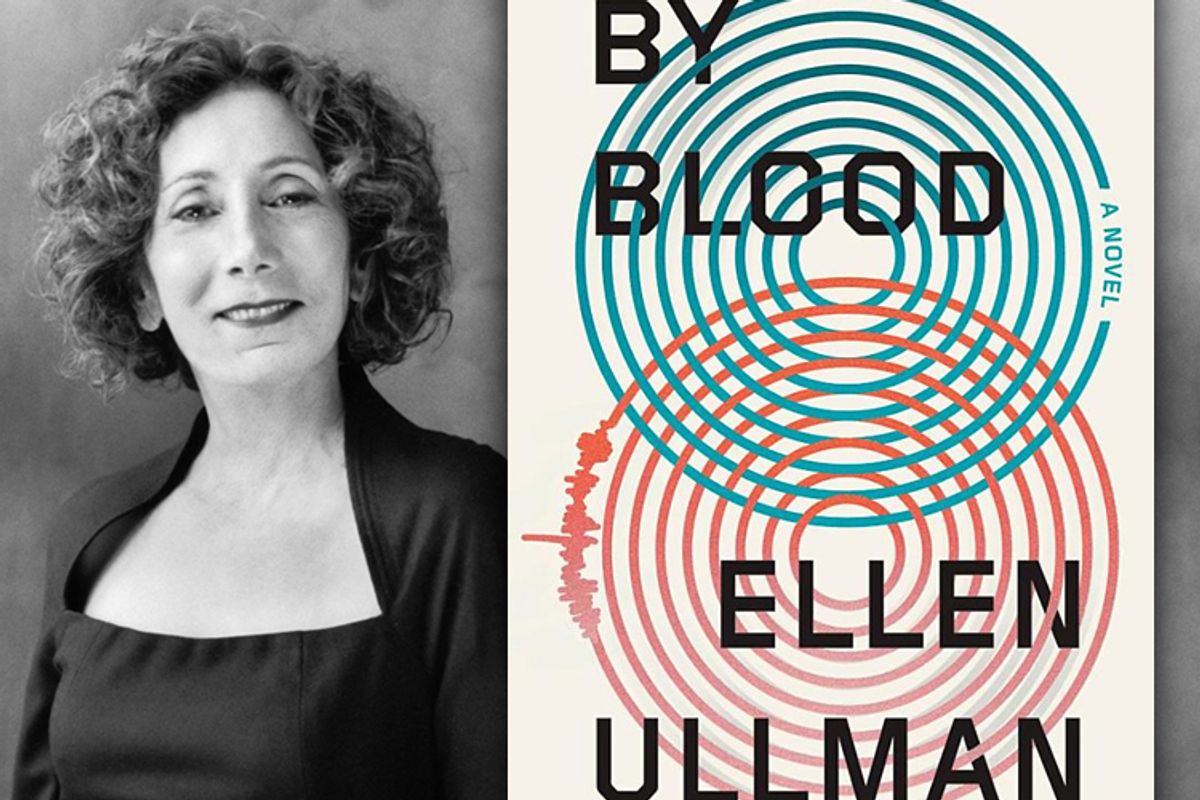

Ellen Ullman is a novelist, critic and computer programmer so well known for her incisive, highly personal writing on technology that when her latest novel "By Blood" appeared, even the New York Times was surprised to discover that it’s set long before the Web, in Zodiac Killer–era San Francisco, and doesn’t involve computers at all. The narrator, a disgraced professor — “the spawn of Kafka and Krafft-Ebing, squirrelly and vaguely deviant,” as Parul Sehgal has said — rents an office in a building straight out of an Edgar Allan Poe story and soon becomes obsessed with the woman whose therapy sessions he hears through the wall.

Ullman tells me that more than a few people have asked her “if I intended to tie his eavesdropping to creepy Internet stalking. No, I didn't. Eavesdropping is a theme with a long literary history.” The narrator came to her one night, she said, when she was working in her own office and couldn’t help overhearing awkward interviews from the matchmaking service next door. Which makes perfect sense. The yen for connection, and the mess people make of actually connecting, has always been one of Ullman’s major preoccupations. Praising her previous novel, "The Bug," Mary Gaitskill invoked Gogol and observed that the story is not merely or even primarily about “the meeting of humans and technology” but about “the remorseless emotional and social system of being acceptably human, which, for some humans, is a near impossible code to understand.”

Ullman’s first book, "Close to the Machine," is a smart, appealingly unpretentious hybrid of memoir and cultural criticism that achieved what until its appearance in 1997 seemed impossible: It made computer programming human. Technology as she portrays it is an inevitable outgrowth of our imagination and drive, almost as inescapable as the longing for love and for sex, but she’s no techno-triumphalist. Ullman exposes the ways the world we’ve created reflects our own shortcomings back at us and isolates us from each other. The computer, she contends, “is not like us. It is a projection of a very slim part of ourselves; that portion devoted to logic, order, rule and clarity.” No matter how good the programming, eventually “the irregularities of human thinking start to emerge” in the code.

Jaron Lanier, whose "You Are Not a Gadget" shares concerns with "Close to the Machine," said at a public event with her last year that when the book appeared, "there was a weird sense of validation" in Silicon Valley. "'Oh, we actually are human here, because someone told a Silicon Valley story on human terms.'"

Writers who’ve discovered it since have had the same experience. Robin Sloan, the talented young novelist and creator of the Fish app, discovered "Close to the Machine" at its reissue last year and praised it in a book review you can read only if you type out his commands in Javascript. “I’ve been looking for a book that explains what it feels like to program computers,” he says. “‘JavaScript Basics’ tells you how code works in the browser ... I want to know how it works in the brain, and in the heart. And I couldn’t find a book like that — not for the longest time. Turns out it was published in 1997.”

Ullman has always written. Like many of her peers who also took up programming in the 1970s, she came not from engineering but the humanities. Yet her mind is as analytically formidable as that of any scientist counting down to the singularity, and she’s able to describe — almost to evoke — what it is to be close to the machine, so close that awareness of the flesh-and-blood self recedes. “We give ourselves over to the sheer fun of the technical,” she writes in the book, “to the nearly sexual pleasure of the clicking thought-stream.” She’s also frank and funny about sex itself, the messiness of it, the irrationality of it. She ends up sleeping with a cypherpunk guy who looks like a skateboarder, “despite the known dangers of cavorting with libertarian cryptographers.”

One of her best works on technology is the 2002 Harper’s essay “Programming the Post-Human,” which was inspired by a scientific task force convened to figure out how to distinguish computer-generated spam from real email and considers the “times when you feel you are witnessing the precise moment when science fiction crosses over into science.”

The problem of machines that can be mistaken for people is especially interesting, Ullman says, because it’s one “we humans have brought on ourselves. It is not a contest of human versus machine, though it is often presented that way; it is instead an outgrowth of what is most deeply human about us as Homo faber, the toolmaker. We have imagined the existence of robots, and having dreamed them up we feel compelled to build them, and to endow them with as much intelligence as we possibly can. We can’t help it, it seems; it’s in our nature as fashioners of helpful (and dangerous) objects. We can’t resist taking up the dare: Can we create tools that are smarter than we are, tools that cease in crucial ways to be ‘ours’?”

This is a question, as she herself says, straight out of an Isaac Asimov story, an instance of “fantasy leak[ing] into everyday life.” I ask her, in email, whether she considers herself an optimist or a pessimist. “I'm a pessimist,” she tells me. “But I think I'd describe my pessimism as broken-hearted optimism.” And that’s exactly the way her writing reads, as if she sees what great things are possible but also the terrible things that are probably inevitable. She wants to pinpoint the exact moments, the precise places, where things go awry.

Ullman writes so beautifully and clearly about technology that people, including very smart people, mistake what she’s about, reducing her to an ephemeral, finger-on-the-pulse sort of writer, when in fact what she’s giving us is much deeper and more enduring than that. The critic Jessa Crispin observes that her philosophical insights endure long after the technologies she’s written about have faded into obsolescence.

Harper’s editor Christopher Beha, author of "What Happened to Sophie Wilder," aptly describes Ullman by email as “a deeply intelligent writer, but it’s a literary intelligence. That is, she doesn’t read like a computer programmer whose experience has made her a great novelist of the cyber communication era. She seems like a natural-born novelist.” This is the part that some readers seem to miss.

Her first novel, "The Bug" (2003), is about a bug that its unwitting creator, a software programmer named Ethan, can’t fix. The errors surface erratically, in demonstrations for important clients and investors. As Mary Gaitskill says in the introduction to last year’s reissue, Ethan is working with programming code, but “he’s living in something much more dense and terrible: the unreadable code of human life expressed in ‘average human thinking,’ and the biology of being ... If Ethan has a literary antecedent, he is Akaky Akakievich, Gogol’s clerk ... [who] is not only paid to copy letters and documents all day, he lives to copy; it is his only pleasure, his only way to understand the world; his code.” Ethan and Akaky and some of the rest of us aren’t lost because of technology or any social or political system, Gaitskill argues; the problem is “a flaw in our very structure.”

"By Blood," Ullman's second novel, is also her best. It combines a confessional intensity freighted with foreshadowing -- as in J.M. Coetzee’s "Disgrace," Vladimir Nabokov’s "Lolita," Mary Shelley’s "Frankenstein" or Donna Tartt’s "The Secret History " — with a paranoiac claustrophobia akin to that of "The Conversation," Francis Ford Coppola’s surveillance masterpiece. The action takes place mostly in two rooms, only one of which the reader can (so to speak) see; the rest of the story is largely overheard. The young woman on whose therapy sessions the narrator eavesdrops, the one whose life he secretly involves himself in, is adopted and has recently discovered, to her Catholic-raised, anti-Semitic shock, that her mother was Jewish. She’s also gay and prone to talking about sex, adding to the narrator’s fascination. In part because of his interference, she winds up traversing strange and terrible alleyways of the Holocaust and its aftermath that have never been explored.

Yet people are hung up on the absence of computers. “I find it funny when someone says that the narrator's search for the birth mother would have taken a few minutes if only he'd had the Internet,” Ullman tells me. “I think that focusing all experiences through the lens of the Internet is an example of not being able to see history through the eyes of others, to be so enamored of one's present time that one cannot see that the world was once elsewise and was not about you. Has Google appropriated the word ‘search’? If so, I find it sad. Search is a deep human yearning, an ancient trope in the recorded history of human life.”

She is at work on another book about technology, a subject that still fascinates her, “but thousands of years of history came before a computer ever existed.” So "By Blood" was a way of “temporarily breaking a link to the computing era, which was becoming rather smothering, a forced way to view the world.” She wanted to explore the idea that the way we live now is “in no way inevitable.” Reading Tony Judt’s "Postwar" convinced her that “small changes could have resulted in a completely different view of the world.”

What makes "By Blood" and all her writing so sharp, so insightful and so timeless is the obsessive way Ullman visits and revisits the intersection between possibility and reality -- “what you have inherited and what you can jettison, what you can possibly escape, and what you cannot" -- you in the individual sense, and in the universal. From every vantage point accessible to her she interrogates “the dreadful question of who we become.”

Shares