CANNES, France – According to “Drive” director Nicolas Winding Refn (who’s also here this year with the ultra-violent “Only God Forgives”), the legendary unmade mid-‘70s film version of Frank Herbert’s “Dune” by Chilean-born mad genius Alejandro Jodorowsky actually exists – and he’s seen it. OK, even Refn hasn’t seen a version of it that can be projected on a screen or played on a high-def monitor, the version that was supposed to star David Carradine, Orson Welles, Mick Jagger and Salvador Dalì. That doesn’t exist. But Refn says he spent a long evening in Jodorowsky’s Paris apartment while the latter went through the storyboards for “Dune” with him page by page, talking through every shot and every line of dialogue. “I am the only spectator who has ever seen this movie,” Refn concludes. “And I have to tell you: It was awesome.”

I don’t hope to see a movie at this festival, or all year long, that’s as inspiring as Frank Pavich’s documentary “Jodorowsky’s Dune,” the story of an enormously influential film that was never made. That may sound strange on a number of levels: How does one of the most famous collapsed productions in cinema history, a failure so dire that it derailed its director’s career for many years, become a source of inspiration? Especially when the resulting documentary largely consists of a man in his 80s sitting around and talking? Well, when the old guy talking is as brilliant, passionate, ferocious and hilarious as Jodorowsky, and when the stories he tells convince you that his quixotic dream of making an enormous science-fiction spectacle that combined star power, cutting-edge technology, philosophical depth and spiritual prophecy nearly came true, it’s as if you glimpse his vision of a transformed world where everything is possible.

The rain-sodden crowd of movie buffs who packed into the Théâtre Croisette here on Saturday night for the premiere of “Jodorowsky’s Dune” (in the Director’s Fortnight sidebar competition) rode with the film for every second; there were several outbreaks of spontaneous applause and a standing ovation for director Pavich when it was over. I gather that aficionados of Jodorowsky and his “Dune” project have seen a good deal of the storyboard art before, along with Chris Foss’ color paintings of sets and design elements. But for the more casual sci-fi fan, this movie delivers a treasure trove of half-familiar images and ideas and opens a window onto an unexplored world that almost was, a world that – as critic Devin Faraci observes in the film – altered the course of pop-culture history without ever existing on its own terms.

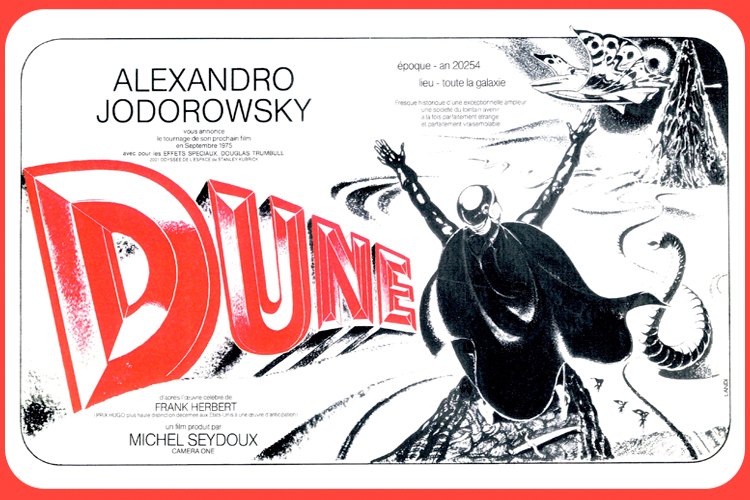

Now, it seems likely, in the cold light of hindsight, that Jodorowsky’s “Dune” would have collapsed for other reasons even if someone had funded it. (He and producer Michel Seydoux fell about $5 million short on a proposed $15 million budget, a vast sum for an art-house director in the 1970s.) Just because Dalì, Welles and Jagger had all said yes, albeit on ludicrous terms – Welles was promised a private chef; Dalì was to be paid $100,000 for every minute he appeared in the final film, and requested a “burning giraffe” – doesn’t mean they would actually have showed up. Furthermore, Jodorowsky’s films to that point, like the international cult hits “El Topo” and “The Holy Mountain,” were surrealistic, visionary LSD-style freakouts that followed no discernible rules of narrative. Could he really have made a densely plotted space opera with many interlocking sets of characters, especially combined with special effects that were barely possible at the time and deep-focus Wellesian cinematography?

It seems impossible. But what you come away from “Jodorowsky’s Dune” thinking is: Hell, just maybe. Jodorowsky had been trained in Europe and South America as a theater artist and circus performer and knew almost nothing about the film industry. But the team he gathered – largely through his own personal charisma and by instinct – was truly extraordinary. He walked out on a meeting with “Star Wars” design guru Doug Trumbull, who was then the highest-paid special-effects whiz in the business, and instead hired the little-known Dan O’Bannon after seeing his work in John Carpenter’s “Dark Star.” French comic-book artist Moebius (aka Jean Giraud) drew the storyboards and character-costume sketches, while Foss, a British artist well known for his science-fiction book covers, supplied color paintings of spaceships and sets. To design the nightmarish sets and costumes for the sinister House of Harkonnen, Jodorowsky found a Swiss surrealist painter named H.R. Giger.

Is all of that starting to sound oddly familiar? Fans of Ridley Scott’s 1979 “Alien,” a movie that did get made and blew the minds of sci-fi devotees around the globe, don’t need me to tell them that O’Bannon co-wrote its screenplay after the collapse of “Dune” left him broke and homeless. Moebius and Foss both worked on the film as well, and of course Giger designed the scariest extraterrestrial monster anyone had ever seen. Remember that Jodorowsky’s “Dune” would presumably have come out before “Star Wars”; when we look at the designs for this unproduced film, we see the birth of a design aesthetic that has shaped both pop culture and the physical world for the last four decades. Oh, and if you’re wondering about David Lynch’s 1984 film of “Dune,” yes, Jodorowsky went to see it, with great trepidation. He was delighted it was awful; not the most noble reaction, he admits, but human.