We're uncertain about the effects of climate change the way we're uncertain that smoking causes cancer, says economist William Nordhaus. "Uncertainty," in other words, really isn't a good reason for us not to do everything possible to stem carbon emissions.

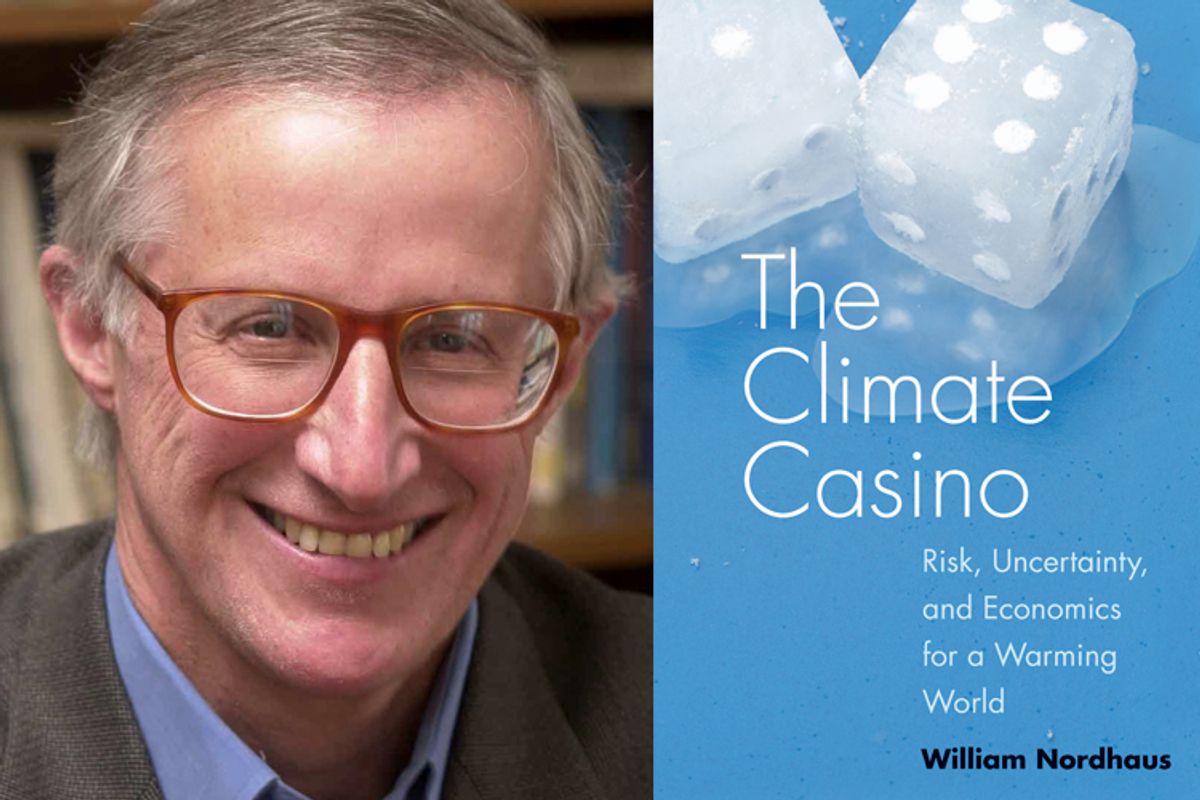

In the latest of his series of books on climate change, "The Climate Casino: Risk, Uncertainty and Economics for a Warming World," Nordhaus, the Sterling Professor of Economics at Yale University, delivers a primer of sorts on the social, political and economic factors at play in the climate debate. It's not whether climate change is happening, he suggests, but what we can and should do about it, that's the true question for our time.

Nordhaus spoke with Salon about his case for a putting a price on carbon, and what we'd have to do to afford and embrace what he says is the only way we have to slow global warming. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

You say in the book that it was written for young people. I’m a young person, so that’s a good place to start: What’s the most important message you’re trying to get across to us?

The most important message I’m always trying to get across is just to use your eyes and your ears and your mind and to think things through for yourselves. And this is particularly important in an area such as this one, which is changing so much – just the facts and the science and the economics of the problem are different now. At least, we perceive them differently than we did 10 years ago. I think it’s important for people to keep their minds open and think about what kinds of solutions we can use.

Why young people? Because I think that young people have open minds. I teach college students and they’re amazingly open-minded. They come in and they want to learn and understand, and that's who this book is for.

The other thing I want to emphasize is that this book is not really so much about the natural sciences as it is about the social sciences. There’s been much written about the ice sheets and the oceans and the atmosphere, but actually not that much about the social science, and not that much about what kinds of tools we need to use or what kinds of instruments we have to slow climate change.

Is there too much of a focus on whether climate change is happening rather than how we can take action against it?

There is, in my mind, much too much attention, among the people who write about it, about whether the globe has warmed, and whether humans are changing it. If you look at the data, there’s just no question. Well, nothing is certain, but it’s extremely unlikely that this is just the normal up-and-down pattern of the daily fluctuations in temperature.

It reminds me a little bit of the people who argue that smoking doesn’t cause cancer. They say, “Well, you know, there is no smoke, there is no cancer, there is no link.” I think it’s just obscuring what we really need to think about.

You wrote a takedown of climate deniers in the New York Review of Books, in which you said, “Yes, there are many uncertainties, but that does not imply that action should be delayed.” How do you get people to overcome that uncertainty?

We face lots of uncertainties, and it’s hard to think about what to do when life is uncertain. If I can come back to the case of smoking and cancer, it’s uncertain if a particular person will get cancer when they smoke. Some people do and some people don’t. But you know that the odds are against you, the odds are heavily in favor of the fact that you’re going to get sicker earlier and in a more serious way.

I think that’s the way I think about climate change. Of course we don’t know exactly what’s going to happen or when it’s going to happen. We can’t see all the ramifications, but they don’t look favorable on the whole. I mean, there are some pretty frightening ones. So I think the uncertainties would make us say, “Well, let’s pay a little insurance premium to slow things down.”

In the book, you make the argument that either a carbon tax or cap and trade are the only ways to get that insurance into play. Can you explain why you see those as the only real solution for reducing carbon emissions?

The big message I want to get across is that the only way that we know -- as economists and as social scientists -- to slow it, is what I call “raising the price of carbon.” And more specifically, raising the price of actions that have emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

The idea is really simple: It’s that people respond to prices, and when prices are high, people use less of things. When the price of gasoline goes up, people use less gasoline; when the price of bread goes up, people have less bread. The idea here is exactly the same: If the price of emissions goes up, then people are going to emit less. And this is not just consumers. If there’s one thing I wanted to get across it’s that. It’s a very simple point, but it’s very elusive and, I think, strange for people, the idea that you do that.

The second point as to why that’s really the way to approach the problem is because it’s so pervasive. It gets in the cracks, it gets everywhere: It operates on consumers, it operates on producers, it operates on inventors, it operates on people who do research and development. Whereas other things we might do, like regulations for subsidies, just affect little parts of the problem. Either one of these -- a cap and trade or a carbon tax – will do it, and as far as I know those are the only ways to do it. Somebody may come up with another way, but I’ve never seen it in all the years I’ve been looking at it.

What would you say the main challenges are to getting something like that applied universally?

Well, there are a lot of them, but I guess I’d focus on two particular ones. The first is just getting people used to the idea that if you want to do something to slow climate change, you have to raise the price of carbon. It’s kind of a strange notion to most people, but you have to keep explaining it and make people comfortable with it. I mean, there are lots of things we do that are strange: Who would think it’s a good idea to have somebody stick a needle in your arm? But every year I get my flu shot, and I’m really convinced it’s a good idea.

That takes a lot of work, and it’s different in different countries. The U.S. has this weird, anti-tax ideology, but not every country does. So we’ve got to get over the hurdle how to do it, and then we’ve got to work with each individual country, and get everyone to work together to take actions to raise the price and do other things to slow emissions.

To that first point, what do you say to people who just wouldn’t be able to afford the increase? You estimate a $25 per ton price for carbon, which would mean an almost 20 percent increase in electricity spending for the average family. Some people say that in order for it to make a difference, it would have to be an even higher price.

Well, first, you don’t have to do it all at once. In fact, I think it would be a good idea to do it gradually, so people can change their lifestyle to accommodate to the changing prices. It’s not something that you want to happen overnight.

If you think of what’s happened to oil prices, it’s been now 40 years since oil prices started going up, and while it’s still painful to pay those high prices, we’ve made lots of adjustments to that over the last four decades. So I see this as a long-term proposition, not something to do all next year or the year after.

The second point is more important: My own thought would be that you would raise this tax, and then you would recycle it back to people by lowering other taxes. It might be, for example, that a typical family would pay, say, $500 in carbon taxes, but they might have rebates on, say, Social Security taxes of roughly the same amount. You could probably rebate as much as you raised, so the average family would be able to have roughly the same post-tax real income.

Now, having said that, clearly some people would do worse and some would do better, so the people who use lots of electricity would be slightly worse off. But to a first approximation, there is no cost of raising taxes. One other way to put that is that we should think of taxing “bads” -- like emissions -- rather than “goods,” like labor and saving and things like that. This is an old theme -- why not tax “bads,” like emissions, and not tax “goods”?

Is there any precedent for doing something like that?

There’s precedent in terms of having rebates, but the idea of doing a trade-off of this kind, I don’t think we’ve ever done that in this country. I think other countries have done it -- some of the Europeans have used environmental taxes or fuel taxes as a substitute for other kinds of taxes -- but we’ve not done it in this country.

To make this work many countries have to work together: The last time a big effort like that was made in the service of the climate was the Kyoto Protocol, and it ended up a failure. What would have to change for this to be more effective?

I don’t think it’s going to work to just get countries together and say, “You have to go along with this; you have to be good citizens of the world; you have to follow some kind of golden rule.” I think that’s the lesson of the Kyoto Protocol, that agreements like that, which are basically voluntary, are ones that countries are not going to follow -- if it hurts them.

So, that leads to the question of what you could do to persuade countries. I have a rather radical suggestion in the book on the use of trade sanctions to enforce a climate treaty. The idea is that you would get a group of countries together to say, “OK, we are going to have a climate treaty, and if you’re not in the climate treaty, then there will be sanctions on your international trade, in terms of tariffs.” That would be the carrot on the stick behind the treaty. It’s a pretty radical idea, and I think many people might oppose it before they’ve thought about it carefully. But I’ve talked about it to a lot of people in the field of international trade, and after a little conversation, I think that they think it’s a good idea.

What about the the national issue of getting bipartisan agreement on what we can be doing to reduce climate change?

Well, I’m an economist -- not a politician or a political scientist -- but I do think that people just need to grow up. I mean, this is a big problem that’s not going to go away. I have a little section at the end of the book on how a conservative economist might look at this -- and I have some conservative economist friends and that is the way they look at it -- but I think it’s going to take a big change. I’m not unrealistic about the difficulties of doing this, but we just have to keep working on it.

How does natural gas play into this? Would setting a carbon price just cause us to ramp up natural gas production?

That’s a complicated set of issues. To the extent that we replace coal with natural gas, we have lots of both climate benefits and environmental benefits. Coal is a very nasty, nasty thing -- it’s got lots of problems other than climate change. It’s a very deadly fuel; we lose probably at least 20,000 people per year because we burn coal. To the extent we can replace it with natural gas, I think we’re better off in all dimensions.

Now in the longer run, there’s not actually that much natural gas, according to all the surveys. As far as we can tell, there’s a lot of it around, but there’s not anywhere near as much of it as coal. The real problems are coal and the other kinds of dirty shales. But in the longer run, the only way we’re going to sort that out is by having prices, like we talked about. And if you put the price on carbon, then you will restrain natural gas as well -- you will restrain primarily coal production, but you’ll also slow down natural gas use.

Do you have any idea how much of an investment there needs to be in renewables, if there were a carbon tax and we were starting to phase out coal?

There are lots of estimates of that -- that’s probably one of the places where the economic models are strongest. We have estimates that, depending on how it’s done, the cost would be in the range of 1 percent of our income over the next five decades or so. So it’s not zero – I mean, if you add that up, that’s a lot of dollars -- but it’s not going to bankrupt us.

Part of it is that it would require that we do it efficiently and effectively: If you do it through a cap and trade, or a carbon tax, you can keep the numbers that low. If you start using very inefficient regulations and subsidies, then it can be much more expensive.

Is there anything else that you want to make sure your readers understand about climate change?

I think for young people, it’s a really interesting set of problems. You can learn a lot about our world -- and not just the natural world, but also the social/economic/political world -- by studying it. I’ve found, by studying it for many years now, that it’s really a laboratory where everything comes up -- from taxes to international law, international trade, treaties and the natural sciences as well. I teach a course on it whenever I have a chance. So, I think that’s one of the messages -- this is, aside from being important, also just really an interesting area to read about and study, and I would really encourage people just to take some time to enjoy the wonderful science in this area.

Shares