Keanu Reeves is wearing a very nice suit and covered in blood. This does not seem to bother him; he greets a visitor with his customary off-kilter bonhomie, bobbing his head in an almost teenage gesture of hello. “Good to see you again, man!” he says cheerfully. It’s true that we have met before but in this job you learn not to put much store in that; as Jack Nicholson once observed, a celebrity meets more people in one year than most people meet in their entire lives.

The blood looks real even when I’m sitting next to him on a sofa, but of course it isn’t. Keanu Reeves is a movie actor — no longer a superstar or a goofy Internet meme — and I’m meeting him in a trailer positioned directly under the Williamsburg Bridge in Brooklyn, with the J train clattering overhead every few minutes. He’s here shooting an action thriller called “John Wick,” in which he plays a retired hit man being pursued by a former colleague. Versions of that story have been told before, and I have no idea whether this iteration will be any good. But Keanu Reeves is about nothing if not about archetype.

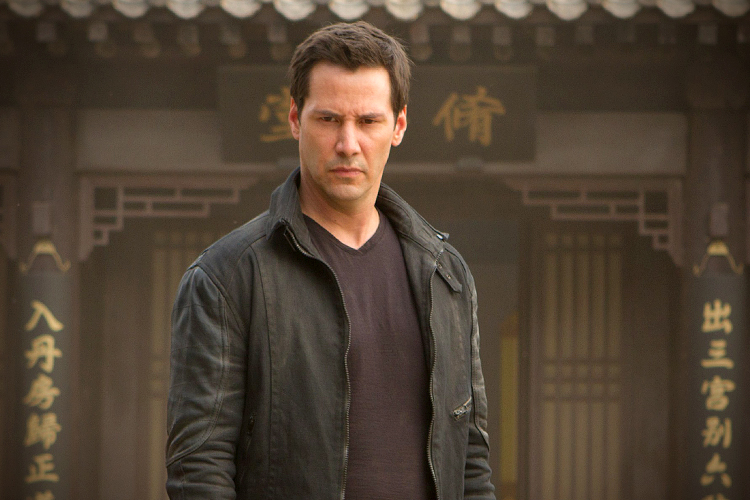

Having spent about an hour and a half of my life in the company of Keanu Reeves, I feel qualified to tell you that he isn’t an idiot, as many people seem to believe. His directorial debut, the Chinese-made martial-arts drama “Man of Tai Chi,” is a clever, calculated and painstakingly crafted work, drawing both on the conventions of classic kung-fu movies of the ‘70s and ‘80s and on sleek, moralistic Asian crime dramas in the mode of John Woo and Johnnie To. If it’s not a life-changing cinematic experience, it’s assured and witty, with a few nibbles at the fourth wall. It unveils a dynamic martial-arts star in longtime stunt man Tiger Chen (a friend of Reeves for some years), and Reeves’ own performance as the Voldemort-like Donnaka Mark, sinister overlord of the Hong Kong underground fight scene, is especially delicious. (Reeves intended to set the entire story in Beijing, but Chinese government censors pointed out that, of course, that city has no criminal underworld and no corrupt police.)

All that said, Reeves on the sofa, covered with fake blood, remains a little hard to read, with a low-affect demeanor very similar to his screen persona. Answers arrive half a beat late or half a beat early, and one gets the unsettling impression that he’s thinking things and not saying them. When I accuse him of employing classic Keanu Reeves iconography in “Man of Tai Chi” – of being self-referential, basically – he laughs and says, “Really? Do tell!” But he talks comfortably about both the thematic and technical questions at work in his movie, and seems entirely at ease, at age 49, with this afterglow phase of his career, where the pressure is lower and the expectations more diffuse.

You’re getting a hard time from some critics on this film, I know. I have the feeling with you that some people are determined to not get it.

Not get what?

I mean, not get everything about you. They have ideas about what you’re like, maybe, and want to stick to those. Do you ever have that sensation?

I don’t know … I don’t know. I mean, hopefully people will enjoy the film. I’m really fond of it, there’s a lot of really great storytelling, action, and there’s some messages in there. I think of it as a cautionary tale.

Yeah, well it is very much in the tradition. It has the classic structure of those movies, going back to Bruce Lee. Did you go to school on those movies when you were growing up? You’re just about the right age for it.

I did. I’ve seen my fair share of kung fu movies. You know, I wanted to make something with Tiger Chen — we collaborated on the story together for five years — and I wanted to make a classic, modern kung fu movie. Obviously, we’re all part of our experiences, so there’s some cinematic homage, some snap zooms and such.

The way you frame it, I guess it is both classic and modern. At the very beginning, it’s like a video game movie, but almost more of the “Mortal Kombat” era than right now. Your character —

But it’s also theatrical. You have this kind of — there’s no credits except for the financiers and distributors. It’s a shot that’s entering a proscenium that’s a world. My ambition and hope was to play a lot with objective and subjective and the fourth wall, and this relationship between the viewer and the medium. So there’s a lot of that dialogue going on, cinematically and storytelling-wise. With the surveillance of the character, with the characters almost looking down the lens — there’s even a certain section where the lead character hits the camera out of the way. But the film, I felt, could carry all of that.

You’ve waited a long time for your first directing effort. What was it about this particular story or character or set of characters that made it the right thing?

I was so involved with the development of the story — you know, for five years when you’re developing a story, so much of your voice goes into it — and eventually, I didn’t want anyone else to do it. It was a story that I wanted to tell. It kind of filled my heart and mind. And so it was personal, in that sense. I think for a storyteller it has to be. And so I didn’t really have a choice.

What I said earlier about people being eager to judge you or misjudge you is interesting here, because the theatricality and artificiality of the film are very calculated. You know what you’re doing and it’s done with a purpose. People can like it or not like it, but I feel like some of the early reviews assume it’s some kind of naive creation.

[Laughter.] No, it’s not naive at all.

You listen to the music, and that’s got all these references in it: a period, ‘70s flavor, an Asian flavor, a contemporary electronic flavor. I feel like your points of reference are all there as well.

Yeah, obviously, working with the idea of tai chi, there’s a lot of binary, complementary, separate, twinning, and these can be from traditional to modern to the instrumentation — there’s a lot of thematic journeys in that. There’s a lot of twinning going on. It just keeps going. Balance, the idea of power and control and meditation, transformation of energy — all that good stuff.

There’s a male lead character [Tiger Chen] in the A story line and a female lead character [Karen Mok, as a Hong Kong police captain] in the B story line.

Mm. There are light and dark masters. Even the female cop has a yin and a yang. My henchmen — all of that.

You’ve done quite a few films with martial-arts choreography in them. Has the more spiritual or philosophical area of those disciplines always appealed to you?

I would say yes, because even when I briefly studied briefly martial arts as a kid, that part was already being spoken about in terms of breath, calmness, collective approach. And developing from that — absolutely, again. By choosing tai chi, you have this possibility of internal and external — you know, chi gong, we do the pushing hands, the philosophical, the meditative, but also the martial form, the tai chi chuan. We invented a style for the film, called tong tai chi, because I didn’t want it to be referenced as “Oh, that’s not yong style. That’s not sun style.” But we used sun and yong, and then the character declares his style by saying, “Oh, it’s my own,” which I hope is making it a journey that is personal, but also could be universal. My character, the dark master, is really exploring Tiger’s desire. I feel there’s a lot of that going on.

Tiger has to come into his own power and then the idea of just having to be thoughtful. We make decisions because we have to, or because we have responsibilities, which Tiger is confronted by in terms of wanting to save his master’s temple, to take care of his parents, all of these things. But those things can also be excuses. “I had to! There’s no other way!” And that’s true sometimes.

Sure. I had no choice! In all areas of life we can create that excuse for our behavior at times.

Yeah, that can be true or it can be a lie. You know, Tiger also is trying to explore — he becomes a master at the end, he becomes a teacher — so for me there’s also the journey of the teacher. The dark master is his enemy, but we learn the most from our enemy. But he’s also, I believe, on a certain level conscious of the journey he’s on. There’s self-awareness, and that I think his light master is complicit with as well.

I very much appreciated the way that your performance as Donnaka draws on classic Keanu Reeves iconography. The things people like, or maybe don’t like, about seeing you on-screen are in there.

Really? Do tell!

I think my favorite line from you is when you’re watching Tiger on TV and you say: “Innocent.” I don’t know how many takes it took you, delivering one word that way …

I know, but it’s delicious, because he’s a carnivore. He stops the screen, right? [Mimicking the gesture, pointing at the screen.] He’s not naive.

He’s hungry. He knows what he wants. There’s always something erotic about that.

Hmm. His view is: You owe me a life. He provides this service of creating this underground fight club, which is not really about the fighting, but the transformation of someone from innocence into a killer. Or to be killed. So I think the idea is, that’s the alternate kind of transformation. Mortal transformation.

This is facile, maybe, but the idea that the dark master is more important than the light master runs very deep. Darth Vader and Luke Skywalker, Voldemort and Harry Potter. Satan and Jesus.

Yeah, absolutely. And when you go to that you’re talking about classic story archetypes. Whether they’re teacher and student, father and son, all of those elements are classic. One of the things I like about the genre is that it works almost like science fiction, in that it can have these archetypes — you can also root them in everyday-ness, but they can also expand, into bigger themes and ideas. So this guy, who is a delivery guy, can be learning tai chi, can also be dealing with issues like, the killer inside us, the part that seeks power and control.

You use Tiger very well physically. Ultimately we see him with his shirt off and he’s very ripped, very muscular. But he’s physically small. For most of the movie he has clothes on and just looks like a kid, not like a fearsome fighter who’s going to kick somebody’s ass.

And when he does cross over into those fights, it’s heartbreaking to see that guy who is transforming, and losing when he’s fighting his master. Donnaka, my character, has that line when Tiger is fighting the twins. “Are you afraid of what you can do to them? Don’t be.” That’s a crazy way to inspire someone. Don’t be human. All that training that you’ve had about compassion and the “other” — just throw that away. Don’t be afraid of hurting them. Tiger’s performance of that, as he comes back up on that stage to do that fight, is moving to me. Where he’s twisted, contorted and that childlike face becomes quite enraptured with violence and lust.

Storytelling offers a kind of control. It can illuminate things and distill things that in life are more complicated and not as cut and dried. But we do come into moments where we do have those kinds of crossroads. And you know, the face of evil in storytelling is often quite exposed. Because I think sometimes in life it’s not. That’s why it takes so much work and dedication to create a story, because you’re creating a kind of order out of life. This fiction that takes all the information of our experience, in order to distill and form and construct, so that we can see it and feel it. [Leaning toward microphone.] And be entertained.

As a first-time director everybody’s going to be looking to catalog your influences, and you’ve worked with a lot of directors in a lot of styles, from your independent-film years onward.

Tim Hunter to Bertolucci. Marisa Silver to Rebecca Miller.

Yeah, exactly. People may forget about those. One obvious thing is that you made three huge movies with the Wachowskis, and I think their influence is in here.

It is, absolutely.

Who else did you pick up tips from over the years?

With all the great directors that I’ve worked with – and this is not omitting anyone, but answering what you’re asking me specifically — I think of Bernardo Bertolucci. [Reeves played Siddhartha in the 1993 “Little Buddha.”] The way he understands form, he can give you practical direction but he can also collaborate, he can also inspire and deal with the philosophical or emotional inquisition or he can tell you not to move your head like that. Also the way he approached his set, his cinema of storytelling. I only witnessed it with him and [cinematographer] Vittorio Storaro, but there was a wonderful thing about how they took in a space and a story. I’m sure they had done their shot listing when they walked through, but there was also an organic aspect to it. That’s always resonated with me, when I had the opportunity to work with him.

He has the reputation of being very manipulative on set. Was that your experience? Did he play mind games with you at all?

A little bit. I mean he didn’t play mind games but he did tell me, about a week before I started filming, that I had to have an accent. And he had told me that I didn’t have to have an accent before that. But he gave me this idea, because I asked him why he wanted me to play Siddhartha, and he spoke about my impossible innocence. That for me was a way to look at the story that we were telling, and look at the fable quality of it. Siddhartha, Prince Gautama before his enlightenment — the way that he looks at the world, that transformation. He gave me a root.

Do you have another directing project on the cards?

I don’t. I’m hunting and searching, looking for a story to tell.

Lastly, I want to bring up “47 Ronin,” the big Japanese revenge drama, which might be a painful subject at this point. [Laughter.] It’s your biggest starring role in years, it went way over budget, there were reshoots, the director was removed, all that stuff. Is that movie finally done? Do you feel OK about it?

I do. I haven’t seen it finished-finished, but I’ve seen a cut of it. Certainly the world-creation, the actors, the story — there’s a balance between the fantastical and the Japanese. For me, I wish it was a little more hard-edged, but I’m not opposed to the fantastical elements. There’s a lot of respect paid to Japanese folklore, and even the fantastical elements are Japanese-inspired. I’m good with it.

“Man of Tai Chi” opens this week in limited national release.