In 1838, the same year that David Ruggles resisted segregation in Massachusetts, Thomas Downing did the same in New York City. A black abolitionist and “celebrated oyster vender,” Downing scarcely had taken a seat aboard the Harlem Railroad when an agent told him to leave. Downing refused, and “the agent and driver immediately seized hold of him, dragged him out, and assisted by two other men, gave him a severe beating, and inflicted a wound in his neck.” Downing sued the agent and driver for assault and battery. When the all-white jury ruled against him, Charles B. Ray’s Colored American observed, “There appears to us to be . . . but little hope in the case of our people, in the courts of justice in this city . . . in any case which comes in contact with a corrupt public sentiment.” “We advise our people,” Ray concluded, “to keep out of legal trials.”

Thirteen years later, two women on their way to church would spark a chain of events that would bring leading black New Yorkers to reject that advice and to organize a movement to desegregate public transit in America’s largest city. It began on a Sunday in July 1854, when schoolteacher Elizabeth Jennings and her friend Sarah E. Adams boarded the Third Avenue horse-drawn trolley car on their way to the First Colored Congregational Church. Upon entering the car, the Irish-born conductor ordered them out, telling them to wait for the next car that had “[their] people in it.” Already late, Jennings and Adams refused to alight. As Jennings and the conductor argued, the driver grew impatient, leading the conductor to allow the two women aboard. He warned them, however, that he would remove them if any passengers objected. Refusing to bow to his insults, Jennings announced that she was, unlike him, “a respectable person, born and raised in New York” who never before had been treated so crudely. The enraged conductor grabbed both women and pulled them out of the car. Jennings fearlessly climbed back aboard. Unable to keep the car segregated himself, the conductor ordered the driver to enlist the aid of the state. A police officer entered the car and pushed Jennings out, taunting her “to get redress” if she could.

Beyond her brazen act of resistance, Jennings was no ordinary New Yorker. She hailed from a middle-class black family with strong abolitionist commitments and a history of combating racial prejudice. Her father, Thomas Jennings, was a successful businessman, a longtime abolitionist, and a leader in the early black convention movement. Her brother, a Boston dentist named Thomas Jennings Jr., was among the many passengers forcibly removed from segregated rail cars in Massachusetts the previous decade. Seeing another of his children victimized by prejudice, Jennings determined to strike back. He joined local blacks who met to condemn the “intolerant” streetcar company and to explore the possibility of bringing “the whole affair before the legal authorities.” Seeking public support, they published their proceedings and Elizabeth’s resistance narrative in the New York Tribune as well as Frederick Douglass’ Paper. The local National Anti-Slavery Standard applauded the efforts, as did distant black Californians who declared that they too would “resist” such outrages “until we secure our rights.” With an eye on bringing suit against the streetcar company, Thomas Jennings crafted an appeal to black New Yorkers, asking them for pecuniary aid. More than the injuries Elizabeth sustained, at stake in this lawsuit would be “the rights of our people.”

Though the burgeoning New York movement involved far fewer white abolitionists than the earlier Massachusetts effort, black New Yorkers still depended on the help of white attorneys willing to represent them in court. Jennings sought out one-time Whig congressman and abolitionist attorney Erastus Culver, who passed the case to his young associate Chester A. Arthur, the future Republican president of the United States. In February 1855, before the Brooklyn Circuit of the New York State Supreme Court, Arthur sought $500 in damages and pointed Judge William Rockwell to the common law of common carriers. Taking the bait, Rockwell instructed the jury that the Third Avenue Company was “liable for the acts of their agents” and bound as common carriers “to carry all respectable persons.” “Colored persons,” he announced, “had the same rights as others” and “could neither be excluded by any rules of the Company, nor by force or violence.” The jury ruled in Jennings’s favor and awarded her $225. To many black New Yorkers and their supporters, especially Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, this “Wholesome Verdict” was a major triumph. Milwaukee’s Weekly Wisconsin agreed. It was time “the absurd and foolish prejudice against colored persons was rebuked, and their rights defended.” This “proper decision” was an excellent start.

This victory provided the basis for further grass-roots mobilization and institution-building in New York. The verdict did not mean every carrier would voluntarily invite black passengers to travel on the same terms as whites, nor did it mean that state or local officials would ensure integration. Ejections continued. In response, Thomas Jennings, joined by two other black leaders, James W. C. Pennington and James McCune Smith, announced “the formation of a ‘Legal Rights League’ ” to ensure the integration of local public transit. Frederick Douglass spurred them on from Rochester, and McCune Smith informed his influential friend Gerrit Smith. “We colored men are organizing a society,” he wrote, “to raise a fund to test our legal rights in traveling &c. &c. in the Courts of Law. Oh that I could infuse an ‘Esprit de Corps’ in my black brethren!”

McCune Smith’s parting lament spoke to his long-standing desire for a wider group of black northerners to join the cause of their own advancement, and it also underscores the importance he and others saw in their new association—the Legal Rights Association (LRA). In 1841 Smith himself had articulated the difficulties blacks were destined to face as a racial minority in a political system governed by majority rule, but he had then left merely implicit the need for black northerners to unite if their “struggle for liberty” was to succeed. More than a decade later and just months before Elizabeth Jennings’s incident, Smith suddenly became more explicit. “The great hindrance to the advancement of the free colored people,” he announced in Frederick Douglass’ Paper, “is the want of unity in action.” Black northerners needed either to treat a “wrong to one” as a “wrong to all” or to find “some general form of oppression continuous in character” that they could all “combine and continuously struggle until we are free and equal.” To Smith, the latter was clearly the “public opinion” that treated black men and women as lesser human beings. A student of American democracy, he recognized that “public opinion is the King of today and rules our land.” With “combined will” blacks needed to “attack public opinion in detail; and each specific victory will strengthen our hands and perfect our organization for the next.” A year later, Smith had found in streetcar segregation a form of oppression that blacks could unite against and found in the Jennings decision a victory upon which they could build. The moment was ripe to improve their “organization,” and the LRA was his answer. It would bind black New Yorkers to defeat streetcar segregation and constitute an important front in the larger battle of the black minority to secure freedom and equal standing in the court of public opinion.

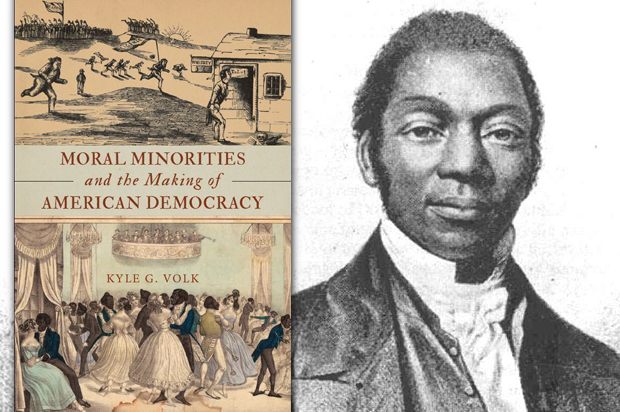

Smith had experienced discrimination while traveling, as had James W. C. Pennington, the other cofounder of the LRA. Born a slave in Maryland, Pennington by the mid-1850s was a recognized black leader. After escaping slavery, he relocated to New York and soon joined Thomas Jennings at the black conventions of the early 1830s. He became a minister and ascended the abolitionist ranks, twice traveling to Europe to represent American abolitionists. On his second journey, Pennington published his own slave narrative and received an honorary doctorate of divinity from the University of Heidelberg. Like other black Americans who traveled abroad, he too had a declining tolerance for discrimination upon his return from a culture seemingly devoid of racism. Throughout the early 1850s he protested segregation aboard ferries and streetcars and scoffed at the continuing rationale for excluding blacks—that “the majority of the public would object to” their presence. By 1855, he was ready to defeat this tyrannical majority.

The creation of the LRA was a pivotal event in the burgeoning minority-rights politics of the mid-nineteenth century, which built on abolitionists’ efforts to uplift free blacks, shelter fugitive slaves, and combat interracial marriage bans, black laws, and suffrage restrictions. No doubt the Equal School Rights Committee formed by William Cooper Nell to defeat segregated schools in Boston provided a model. Their choice of title—“rights association”—may also have been influenced by the contemporary proliferation of southern rights associations, liquor dealer associations, and women’s rights associations. But the LRA had more direct roots in the work of Hezekiah Grice, a black Baltimorean who had originated the idea for the black convention movement. In 1831, he spurred other black leaders to form a “Legal Rights Association,” which solicited written opinions on the “rights and citizenship of the free black” from prominent white statesmen and attorneys William Wirt, John Sargent, and Horace Binney. All three men declined to weigh in on such a controversial topic, but Grice’s efforts influenced Jennings, Smith, and Pennington. At least according to the Anglo-African, Grice deserved credit for inaugurating “two of the leading ideas on which our people have since acted”—the convention movement and “the struggle for legal rights.” By 1855, the LRA had taken up the latter cause, implementing a new strategy of rights advocacy that differed from the black convention movement’s focus on annual meetings and petitioning. The LRA’s reliance upon local mobilization, organized civil disobedience, and strategic legal challenges would serve as a vital model for future efforts to secure minority rights.

The LRA’s leaders sought to persuade local officials that the Jennings decision bound all the city’s public carriers and to convince their black brethren to assert their right to ride. Through petitions and public letters, Pennington urged New York’s mayor, Fernando Wood, to “restrain” streetcar companies from removing black passengers and to instruct the police not to aid conductors in removing blacks. Pennington used the abolitionist press and his pulpit to rally local blacks to the cause, urging them to “show a bold front in this and other kindred matters of equal importance.” The LRA’s leaders also initiated a disobedience campaign. They encouraged black men and women to enter the cars, resist ejection, and seek legal redress, and they sought to jump-start this effort by capitalizing on the “Anniversary Week” in May 1855 that made New York City the epicenter of the broad struggle against slavery. Between the numerous meetings, abolitionist visitors would ride the streetcars, and the LRA’s leaders determined to put their local battle on a national stage. To structure the effort, Pennington published instructions in Frederick Douglass’ Paper for black men and women to board New York’s ferries and streetcars with confidence. “If any driver or conductor molests you,” Pennington explained, “have him arrested, or call upon Dr. Smith, 55 West Broadway, Mr. T. L. Jenning[s] , 167 Church-st., or myself, 29 Sixth-av., and we will enter your complaint at the Mayor’s office.” The LRA’s leaders were ready for battle.

One of the first encounters involved Sidney McFarlan, who boarded the Sixth Avenue Railroad’s “white persons” train, as he put it, to “test the question whether persons of his shade could ride on the white folks’ car, or not.” After being ejected, McFarlan had the conductor and driver arrested. In front of a full courtroom, a police court judge dismissed his case and repudiated the LRA’s tactics, claiming that McFarland improperly had “provoked the assault.” Nonetheless, “a number of others” continued to enter the cars, and on May 24, 1855, Pennington himself joined the fray. After he refused to leave a Sixth Avenue whites-only car, a “ferocious” driver “forcibly laid hold of him and ejected him.” After finding no relief in police court, Pennington announced his intent, as newspapers as far away as Indiana reported, “to test the validity of this exclusion” before the Superior Court of New York. His case, which took over eighteen months to come to trial, became the LRA’s most widely discussed legal challenge.

Pennington’s ordeal brought some to examine even more fundamental questions of democracy, namely the power of majorities. Segregationists continued to proclaim that transit companies should follow the majority’s wishes and that the black minority should not force themselves “in where a large majority do not wish.” This gave Frederick Douglass pause. Pennington’s incident prompted him to muse publicly about French visitor Gustave de Beaumont’s observations about racism and democracy. To Douglass, “the spirit which dragged Dr. Pennington from the public car” was analogous to that which drove “the colored man from the lower floor of [America’s] Christian (?). . . churches.” It was Beaumont, Douglass informed his readers, who along with his travel companion, Alexis de Tocqueville, had tied the power of democratic majorities to America’s degradation of blacks. “In a congregation of fashionable people,” Beaumont wrote in his antislavery novel Marie, “the majority will necessarily have a mind to shut the door against the people of color: the majority willing so, nothing can hinder it.” For Douglass and perhaps many of his readers, Pennington’s case proved Beaumont correct by again exposing the majoritarian underpinnings of black inequality. To them, the LRA’s battle was not only against streetcar companies and racism. It was for the rights of the black minority and against the absolute rule of majorities that was corrupting “democracy” itself.

In the months following Pennington’s altercation, LRA leaders continued to develop the tactics essential to their rights campaign. In August 1855, “the most intelligent colored citizens in our vicinity,” according to the Tribune, assembled in Brooklyn, selected Thomas Jennings as president, and signed a constitution. From that point, expanding the membership became their priority. Success would rest on the group’s ability to reshape white opinion on the question of black rights and to obtain a following of black men and women who were committed mind, body, and purse to the cause. At weekly meetings participants gave and heard speeches, discussed the changing conditions of transit, debated resolutions, and crafted petitions urging the state legislature to intervene on behalf of black riders.

Disobedience and civil litigation, however, remained the centerpieces of the LRA’s rights politics. LRA members agreed to take seats aboard streetcars and if “hindered, molested, questioned, or in any way treated different from other citizens” to seek legal redress. Though the LRA left no official records, making the full extent of this campaign difficult to assess, newspaper evidence reveals that members regularly confronted discrimination and initiated lawsuits through the early 1860s. The LRA, of course, hoped this approach would yield favorable rulings, and it took advantage of New York City’s expansive system of lower courts by initiating suits that tested the positions of varied juries and judges. Beyond seeking victories in the courts, the LRA’s litigious ways pestered the companies that refused to integrate (as well as their agents who ejected black riders), testing their resolve in the process. These courtroom dramas also provided continued spectacles that ensured segregation would remain before the public.

A key obstacle to this court-centered crusade was cost. From the outset, the LRA established a legal defense fund that members could access should they challenge segregation in court. Members paid an “initiation fee of 25 cents and five cents monthly dues” and dropped spare change in a contribution box that circulated at meetings. Black women, who participated in meetings, fought in the streets, and served as litigants in several lawsuits, also played a vital fundraising role. Building on the efforts of Nell’s Equal School Rights Committee, the LRA’s “Female Branch” held annual galas commemorating “the decision by Judge Rockwell” in the Jennings case. Ticket sales helped grow the LRA’s coffers, but equally important, the gathering allowed politics and pleasure to mix. The three hundred attendees in 1856, for example, supported the cause while socializing, consuming an “excellent” meal, and engaging in “promenading and vocal music.” These all-night festivals, the Tribune observed in 1858, were essential “to keep alive the interest in the Society.”

Despite their best efforts, the LRA did not convince most black New Yorkers to join the association. Of the more than 12,000 local blacks, the association only ever brought a few hundred participants to any one of its functions, and its expenses, wealthy oysterman Thomas Downing grumbled, “had to be borne by a few only.” The LRA also had to weather public criticisms, including those of unconverted local blacks. Most notably, Joseph R. Rolin, a black man reared in an elite white family, repudiated the LRA’s efforts in print and even attempted to derail an LRA meeting in person. To Rolin, the association’s so-called leaders were self-aggrandizing tools of white abolitionists. The approach of “forcing ourselves” into cars and resorting to courts of law was unmanly and made “us, the minority, the enemy of the white majority.” “I am a man of peace,” Rolin declared, “and seek no rights that are not given to me by public consent, and do not believe in those acquired by force of law.” Real men would adopt a strategy of self-help and education so that the next generation could be “useful and respectable members of society.” Only through patience, uplift, and avoiding “angry strife with the majority” would the black minority defeat prejudice and secure their rights.

Rolin was not alone. At the peak of the LRA’s action in 1855, a commentator in the New York Times declared the LRA’s approach “the least judicious of several possible ones.” It unrealistically hoped for a “sudden revolution” and foolishly proposed “to carry the most elevated positions in society by storm; to contest the ascent to positive equality, by one petty skirmish after another, reckoning on a final victory over that last enemy which is to be overcome, the prejudice of color, by some final and forcible coup de main.” According to this author, prejudices were unconquerable, and the LRA’s “litigious and vexatious plans” would only strengthen them. Black New Yorkers would be better off concentrating on “self-elevation, by moral and educational means.” Alluding to colonization schemes, the author suggested that blacks should remember that they had chosen “to remain among the whites.” If unwilling to leave the United States, blacks instead might follow the Mormons and use “portions of our own vast territory” to found their own community. In other words, a better way for minorities to establish their rights was to flee hostile environments and to form separate communities. Barring such geographic “segregation,” if “the negro . . . chooses to remain,” he should “accept the terms of his choice with all possible patience.” Only “time” would mitigate “the popular aversion against color.”

These critics no doubt represented many Americans, black and white, who rejected the LRA’s aggressive style of rights advocacy. Many probably agreed that it was better for black northerners to avoid conflict, accept the status quo, work hard, and hope that equality would come in due time. Alternatively, the reference to the Mormons’ exodus to Utah signaled that for some northerners, emigration was a legitimate tactic that oppressed minorities should consider. Even among some black activists, emigrationism—a position scorned by earlier black leaders—had gained adherents as life for black northerners seemed to worsen in the 1850s, not least because of the terrors of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. For Martin Delany, the foremost emigrationist of the era, the key reason blacks should consider leaving the United States was because of their “political position”—they likely would always be a minority. It was their “numerical feebleness” that made “equality of rights” seem an impossibility. Better to go “where the black and colored man comprise, by population, and constitute by necessity of members, the ruling element of the body politic.” To Delany and his followers, it was not the American West where black majorities would rule but rather in the Caribbean and Central and South America. As conditions for black northerners continued to worsen in the late 1850s, the LRA would come to count emigrationists in its leadership corps, including militant abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet. Nonetheless, its mode of minority-rights advocacy, which was predicated on gaining equal access to a racially integrated American public, contrasted with the exit strategies that the Mormons initiated and those that Delany and others sought to implement. When the abolition of slavery brought far greater numbers of black Americans to advocate for rights as minorities, the LRA’s strategies to shape law and public opinion would provide a useful guide.

Reprinted from “Moral Minorities and the Making of American Democracy” by Kyle G. Volk with permission of Oxford University Press. © Oxford University Press 2014. All rights reserved.