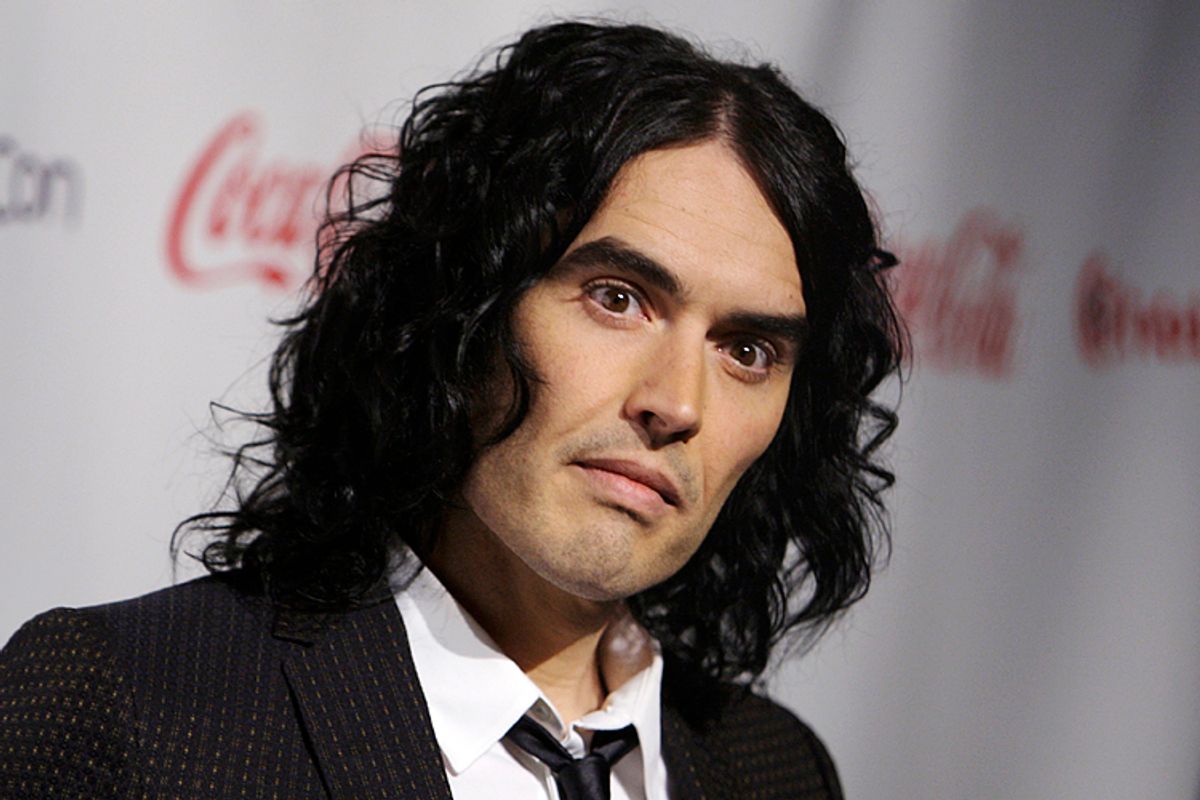

Last year, Russell Brand declared in a New Statesman article that he had never voted because he "regard[s] politicians as frauds and liars and the current political system as nothing more than a bureaucratic means for furthering the augmentation and advantages of economic elites.” And Brand, in many ways, is right — just not about voting. A growing body of political science literature actually finds that voting is an incredibly important lever of policy change. To understand why, though, we need to start with the matter of class.

The class bias in voter turnout in America is strong. A recent study estimates that in 2008, voter turnout among the wealthiest 1 percent of the population was an astronomical 99 percent. It's not surprising that this level of participation doesn't hold for all tax brackets; yet the chart below still shows a startling trend. There is only a single instance over the past three election cycles of a lower income bracket having higher turnout than a higher bracket.

For a long time, political scientists weren’t worried about turnout disparities. In their seminal 1980 study on the question (using data from 1972), Raymond Wolfinger and Steven Rosenstone argued that, "voters are virtually a carbon copy of the citizen population." Later, in a 1999 study, Wolfinger and Benjamin Highton find a slightly larger gap between voters and non-voters, but still conclude that “non-voters appear well represented by those who vote.”

However, in a more recent review of the data, Jan Leighley and Jonathan Nagler find “enduring and increasing” differences between voters and non-voters on issues relating to class-based issues. They find that non-voters are far more likely to support union organizing, a job guarantee and universal health insurance.

Why the differences in the studies? It turns out, the reason is historical. Difference between voters and non-voters with regards to the size of government and redistribution weren’t as strong in the 1970s and 1980s, when the earlier studies were conducted; since then, according to Larry Bartels, the U.S. has become a world leader in class conflict over government spending. These biases began accelerating at the end of the 1980s.

Since then, the Leighley and Nagler thesis has enjoyed increasing support. A 2012 Pew survey revealed similar differences, with non-voters far more supportive of government intervention in the economy and far more supportive of the Affordable Care Act. A Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) study of Californians from 2006 finds that non-voters are also more likely to support higher taxes and more services. They were more likely to oppose Proposition 13 -- a constitutional amendment that limits property taxes -- and to support affordable housing.

Given all of this, it’s unsurprising that the current Republican electoral strategy is based around disenfranchisement through means like voter ID laws. Consider a Pew poll taken from before the 2012 election: Among “likely voters,” Obama and Romney were split, with 47 percent of voters each. Among non-voters, however, Obama had 59 percent support, compared with Romney’s 24 percent support.

One problem with this is that turnout inequality affects both parties -- pulling the Democrats and Republicans to the right. The corollary is that voter suppression efforts pursued by Republican partisans also affect the behavior of Democrats. And there is strong evidence that voter suppression efforts increase turnout inequality.

For instance, one study finds that “state voter registration laws pose a substantial barrier” to the mobilization of low-income voters. While 63.2 percent of citizens in the lowest income bracket (less than $10,000) are registered, a full 87.1 percent of those in the top bracket ($150,000 or more) are. Research shows that same-day registration decreases the class bias of the electorate, so rollbacks of same day registration will also harm low-income voters.

It’s important to note that the gap between registration and turnout is higher for low-income citizens. A bit more than 16 percent of registered low-income citizens don’t vote, while only 6.9 percent of registered citizens in the top income bracket don’t vote. (See chart) Much of the problem, then, is getting low-income voters -- who are hampered by voter ID laws and reduction in early voting -- the the ballot box. It’s unsurprising that an investigation of Republican voter suppression efforts finds that “larger increases in class-biased turnout, indicating higher turnout among lower income voters relative to wealthy voters, is significantly associated with a larger volume of proposed legislative changes.” This finding was confirmed by a study of Indiana’s voting law by Matt A. Barreto, Stephen A. Nuño and Gabriel R. Sanchez.

Where class bias is lower, the poor benefit. Christopher Witko, Nathan Kelly and William Franko studied 30 years of data on turnout inequality and find, “where the poor exercise their voice more in the voting booth relative to higher income groups, inequality is lower.” Their results show that lower turnout inequality leads to significantly more leftist governments and significantly more liberal economic policies. In currently unpublished research, James Avery studied the period between 1980 and 2010 and finds “unambiguous” evidence that increased turnout bias leads to “greater income inequality several years later.”

This means that the impact of voting goes beyond simply elections.

In the wake of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, long-term Democratic incumbents shifted their voting behavior to respond to the newly mobilized Southern black electorate.Thomas Hansford and Brad Gomez studied more than 50 years of data and find that the “effect of variation in turnout on electoral outcomes appears quite meaningful.” One recent study finds that where there is less class bias in turnout, party policy platforms are more favorable to the poor. James Avery and Mark Peffley find that states with low-income voters turned out to vote, politicians were less inclined to pass restrictive eligibility rules for welfare. Political scientists Kim Hill and Jan Leighley find in two studies that states with a more pronounced class bias, social welfare spending is lower. David Broockman and Christopher Skovron find that legislators tend to overstate the conservative attitudes of their constituents. This could be because their constituents tend to be wealthier. One study of wealthy citizens finds that, “on economic issues wealthy Democratic respondents tended to be more conservative than Democrats in the general population.”

Voting should only be the beginning of political change; it should not be the end. It is, however, necessary. In their study, Hill and Leighley find, “it is the underrepresentation of the poor, rather than the overrepresentation of the wealthy” that explains why states with high turnout inequality have low social welfare spending. The fight to reduce the influence of the wealthy will be a long one, but it begins at the ballot box.

So don't listen to Russell Brand. Vote.

Shares