There’s so much that is brilliant and unexpected and often downright thrilling about “Mommy,” the fifth feature (a fact amazing in itself) from 25-year-old Quebec enfant terrible Xavier Dolan. Here’s one relatively minor but impressive example: He borrows “Wonderwall” by Oasis, perhaps the most overplayed and overloaded rock anthem of the ‘90s, for a sequence that reveals all the liberatory and celebratory and explosive potential of the song as if we’d never heard it before. For Dolan’s exquisitely rendered, downwardly mobile suburban characters – a vivacious and troubled single mom, her profoundly unstable teenage son and their neurotic, unhappy neighbor – it signals a moment of possibility and escape, a moment as transient as the song itself.

If you don’t have any idea who this guy is, you’re not alone. Dolan has been a specialty interest all along, a film-festival fave-rave, both because he comes from an insular minority culture within North America and because his films are so intimate, personal and specific, even within the French-Canadian milieu. I don’t suppose “Mommy” will totally transform that equation. In formal terms, it’s a work of deliberate perversity, shot on 35mm film (by cinematographer Colombe Raby) in a completely square 1:1 aspect ratio, with the exception of one scene I won’t describe. Whatever you make of that peculiar aesthetic choice, this is also a major step forward for a young filmmaker whose enormous talent for visual composition, for sound-and-vision montage and for capturing a moment in all its sensuality and intensity has previously been accompanied by a sandpaper-on-chalkboard level of self-absorption. (In fairness, that began to change noticeably with “Laurence Anyways” in 2012, which is overly long but mostly terrific.)

“Mommy” is a passionate and generous portrait of three intersecting lives on the drab outer margins of middle-class society, told without condescension or sugary coating by an artist taking full command of his powers. Dolan has taken a crucial step back from autobiography (I am guessing) and made a deeply moving near-masterpiece with a much wider potential audience. If you’re close enough to the cinephile world that you’ve been following Dolan’s career, then you already know that “Mommy” marks a return to the obsessive, inappropriate and borderline incestuous mother-son relationship of his debut film, “I Killed My Mother,” which Dolan wrote, directed and starred in -- at age 19.

That film was the work of an extravagantly gifted teenager, but still a teenager, with its solipsistic focus on the suffering of Hubert, the artistic and misunderstood gay son played by Dolan, who is plagued by the unforgivably bad taste and emotional manipulations of his suffocating mom. “Mommy” is less a remake of “How I Killed My Mother” than a fundamental reconsideration of its theme. Dolan has taken himself out of the picture and shifted the focus; the central character is now Diane (or “Die,” as she styles herself), the wondrous and appalling widow magnificently played by Anne Dorval, who was also the mom in the 2009 film.

As I see it, Dolan has looked back at both his first film and whatever his real-life situation was, and come to understand that his mother makes a far more interesting character than he does. With her sprayed-on designer jeans and platform shoes and teased hair, her boxed wine and her running battle between cigarette smoke and air freshener, not to mention her incomprehensible blend of flattened-out Quebec French and fragments of English slang, Die is a magnificent train wreck. She’s sexy and she’s trying disastrously hard to be “sexy.” She’s vivacious and resourceful and more than a little bit desperate, and you root for her all the way while feeling profoundly grateful not to be her child or partner or in any way related to her.

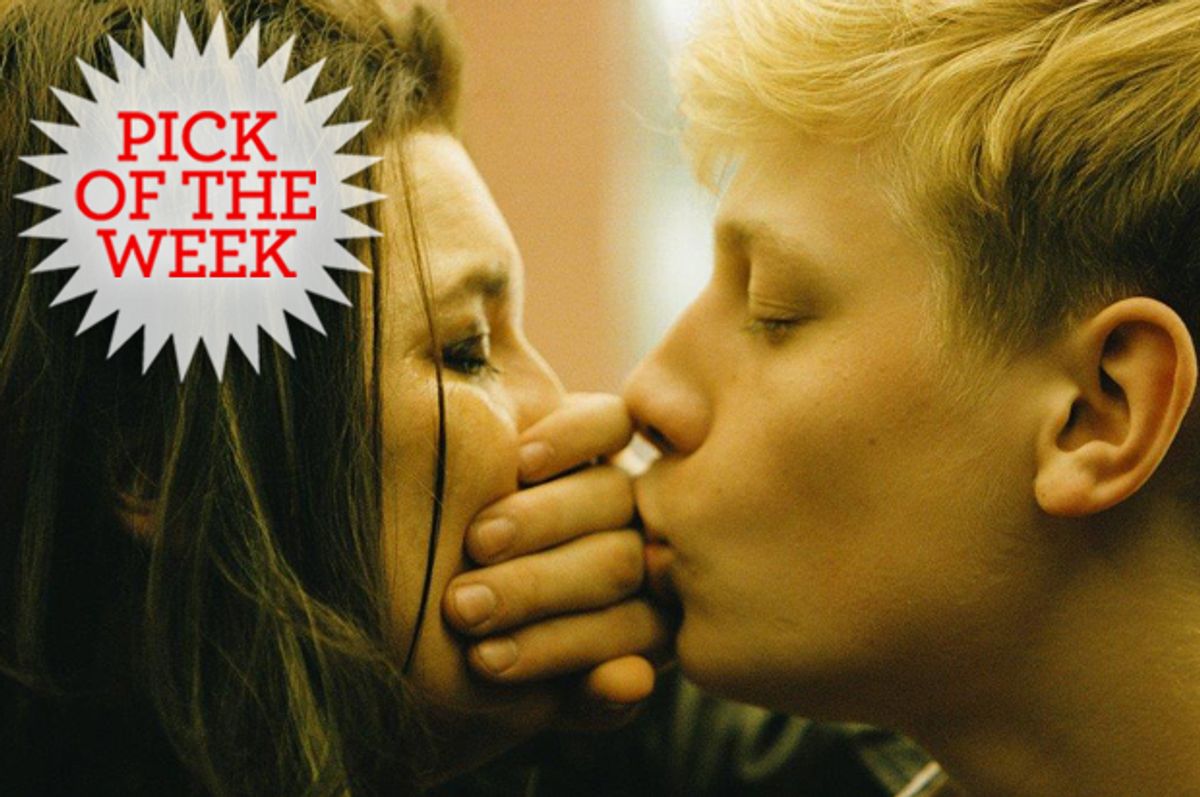

“Mommy” is very much Die’s personal odyssey through the triumphs and defeats of her tormented relationship with Steve (Antoine-Olivier Pilon), her handsome and violent son, who’s been in and out of institutions since his dad’s death a few years earlier. In direct opposition to Dolan’s first film, we experience Steve entirely from the outside, as a charismatic, gleeful, profane and dangerously unpredictable force – a wild animal in human form, or a geological fissure waiting to erupt. He smashes up the apartment after his mom asks him to take his medication, and launches a tirade of racial abuse at a cab driver who won’t turn down his radio. Steve may well be gay, but he may also be straight or bisexual or not quite figuring that stuff out, and that question plays virtually no role in the story. He does start a fight in a karaoke bar, after some idiots call him the F-word because he wants to sing an Andrea Bocelli song, but I don’t think that’s dispositive evidence either way.

After Steve gets kicked out of some specialized boarding school for starting a fire that severely injured another student (picky, picky), Die makes a good-faith effort, at least by her standards, to get her act together. She vows to make some money and educate Steve at home toward the Canadian equivalent of a GED and keep him out of prison and/or the psychiatric ward, which seem like increasingly likely destinations. These two wounded ducks are hopelessly lost with each other, until they find an unlikely ally in Kyla (Suzanne Clément), the marooned housewife across the street, who turns out to be a high-school teacher on endless sabbatical because she suffers from a severe panic disorder and a crippling speech defect.

Terminally unsure of herself and defeated by life as she seems, Kyla represents a realm of education and achievement that Die and Steve can barely imagine. She holds out before them the dreamlike and perhaps illusory possibility that Steve can get better and escape from the doldrums of Quebec to college in the United States (viewed here with a classically Canadian combination of envy, hatred and desire), and by seeing herself reflected in their eyes she gains in confidence. Dolan never loses sight of the tension, and even the potential violence, below the surface of this three-way relationship: Even amid drunken girl-talk there’s a huge gulf of class and life experience between Die and Kyla, and Steve’s puppyish eagerness for the approval of a somewhat appropriate adult authority figure frequently threatens to boil over in unsavory ways.

When Steve sheepishly assures Kyla that he’s actually a good guy, after one of his not-quite-rape efforts to feel her up, we have to laugh. But it’s the laugh of recognition, not of mockery: Steve believes what he says, and Kyla halfway does, and we want to. But how are we to judge someone’s goodness: by his capacity for love and his yearning for something better and his puckish if intermittent good humor? Or by his actual behavior, which in Steve’s case is largely unacceptable? This is a perennial problem in human life, and not one that yields to an obvious solution for the agonized Die or anybody else. I don’t know whether Dolan was thinking of Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu’s famous observation that life’s tragedy begins with the bond between parent and child, but “Mommy” is a gorgeous and heartbreaking illustration of that theme, rendered with poetic intensity, exquisite visual craftsmanship and a ribald middle finger.

"Mommy" is now playing in New York and Los Angeles, with wider release to follow.

Shares