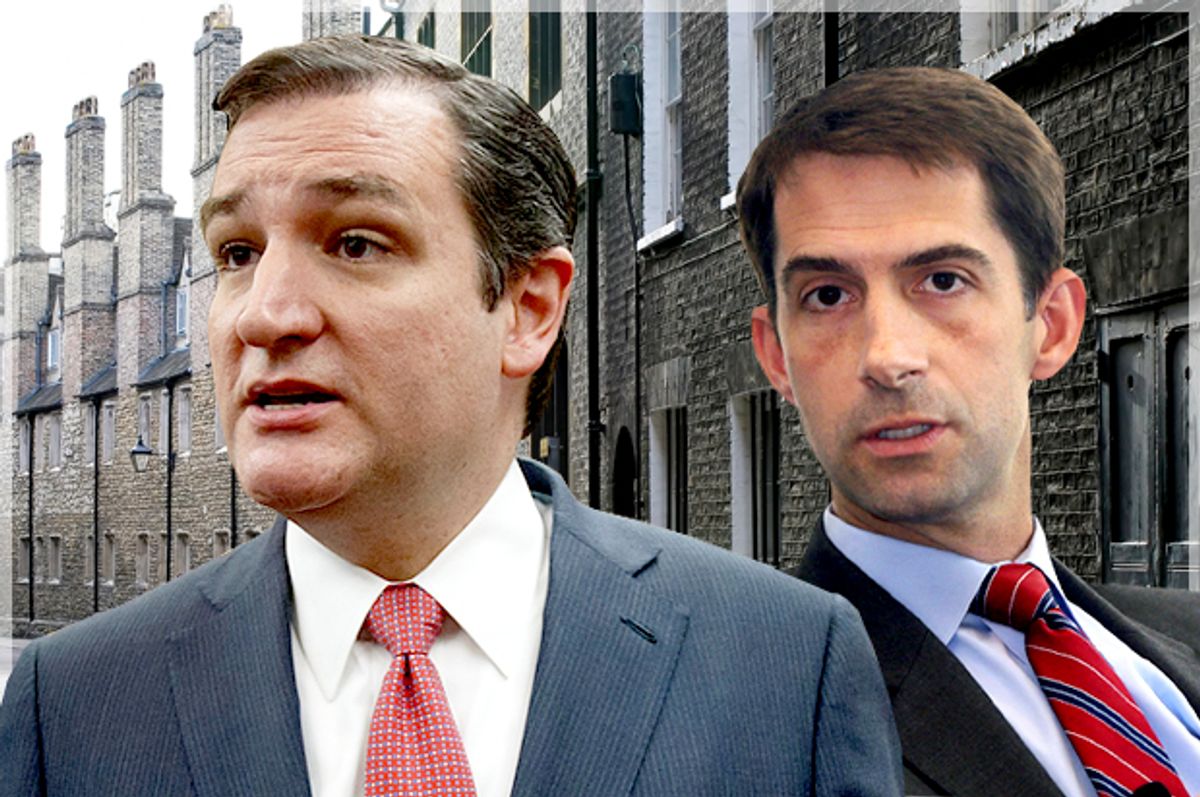

To make sense of the distorted dream world of American politics and its perplexing Lewis Carroll rhetoric, we sometimes have to look beyond familiar categories and recent history. This week, for instance, we get to look clear back to Victorian England, a longtime source of fascination for American conservatives and, at least in its stereotypical form, a cryptic role model for today's Republican Party. The GOP's House and Senate majorities have unveiled their budget proposals, a fantastical and mendacious set of documents worthy of Mr. Bumble, the comic villain and font of incoherent conventional wisdom in Dickens' "Oliver Twist." Most people will ignore these proposals, for the sensible reason that they will not be enacted. But behind the patriotic-imperial posturing and foreign-policy bluster that have grabbed headlines lately, these imaginary budgets provide a glimpse of the rapacious utopia envisioned by the Koch brothers and their Tea Party-infused ideological mouthpieces, including Tom Cotton, Ted Cruz and Scott Walker foremost among them.

The Kochs and their allies are not conservatives at all, in any traditional meaning of that word. They represent the revolutionary resurgence of Big Capital as a class -- enlightened, self-aware and devoted to its own interests. If that terminology sounds impossibly old-fashioned, their impossible dream to undo a century and more of welfare-state policies is a throwback as well. When you hear Cotton call for the building of more and more prisons – by far the most expensive and least effective means of addressing poverty -- or declare that food stamps (which feed roughly one in six of his fellow Arkansans) nurture a slothful underclass of criminals and drug addicts, something deeper is at work than the obvious level of dog-whistle racist pandering. He is also channeling the Victorian establishment's ideology on poverty, virtually without alteration.

As Dickens observed in “Oliver Twist,” in essence a satirical broadside directed at the Poor Laws of his time, the unequal distribution of wealth was understood to demonstrate character and to reflect the dispensation of Providence. Those who fell into poverty or were born into it, like the novel’s hero, clearly lacked moral fiber, and were prone to laziness and ingratitude. Cotton’s argument that prisons have a bracing effect on society, while the vastly cheaper option of providing the poor with food and medical care weakens it, follows the same line of reasoning as the “sage, deep, philosophical men” of Oliver’s hometown, who discover that paupers like the workhouse too much: “It was a regular place of public entertainment for the poorer classes; a tavern where there was nothing to pay; a public breakfast, dinner, tea and supper all the year round; a brick and mortar elysium, where it was all play and no work.” (The remedy, of course, was the famous bowls of gruel, which Dickens observes led to a dramatic increase in the undertaker’s bill.)

I don't know whether the GOP’s new golden boy actually understands that he comes off like an unctuous Dickensian parson, cloaking cruelty and cupidity in the rags of virtue, but either way it's a mistake to dismiss him as a Southern-fried idiot who's just reading his lines from a Koch-authored script. To employ a metaphor he would appreciate, Cotton is an effective quarterback, a charismatic figurehead smart enough to execute the playbook. You could even argue that political lightning rods like Cruz and Cotton, who make no effort to disguise their radical agendas, serve to distract us from the men behind the curtain. I don’t believe that the true political genius of the Koch brothers, or the depth of historical analysis that drives their strategy and tactics, have remotely been appreciated by their enemies. To this point, they have been smoother, smarter and better prepared than anyone who has tried to expose them or combat them.

Among other things, the warriors of Big Capital have grasped a central truth of American politics that many liberals continue to avoid or deny, and seized upon the opportunity it presented. The Democratic Party has largely abandoned economic or fiscal policy as an arena of combat, in favor of cultural issues where it perceives a demographic edge, and barely even pretends to represent the interests of poor people or the working class. So while the renewed class war fueled by the Koch zillions has sparked considerable concern and alarm among the Paul Krugman sector of the population, it has encountered almost no coherent or concerted opposition.

There’s no way to overstate the importance of this. Despite the well-understood factors that have produced Democratic popular-vote pluralities in five of the last six presidential elections, the ideological vacuum on the mainstream American left has opened the door for a string of reactionary victories that at first seem illogical or anomalous. If the forces of Big Capital can no longer reliably command an electoral majority by wrapping themselves in flag-waving propaganda and an incoherent litany of “culture war” issues, they can do something even more effective. Convincing large numbers of working-class and middle-class Americans to vote against their own interests for decades was a big win; convincing an even larger number to give up on democracy altogether is even bigger.

By paralyzing the political process, manipulating the Democrats’ institutional spinelessness and driving public discourse ever further to the right, the warriors of Capital have shrunk the electorate to historic lows and drained Congressional elections of any evident drama or meaning. As I have already argued, Democratic loyalists who blame widespread voter apathy for their 2014 midterm defeat have it backwards. That election’s staggering 36-percent turnout -- the lowest since World War II -- was the real victory of the Koch forces, and much more important than the gerrymandered Congressional majority that came along as a bonus.

Yes, I used the radioactive phrase “class war,” and I don't mean it in some metaphorical sense. The plutocrats have a dream, and it looks more likely to come true than Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of hearing the bells of justice and freedom ring from every molehill of Mississippi. Big Capital has reopened the great class war of Victorian England, the brutal conflict so vividly depicted by Dickens and Karl Marx, and longs to pursue it to total victory. The Industrial Age has given way to the “information economy,” and the labor movement lies in ruins. As for the international proletariat that Marx envisioned as the protagonist of human history, it has been dispersed among Walmart stores and Verizon call centers, stripped of any sense of collective identity or “class consciousness,” and largely convinced that it does not exist. Victory is nowhere near as distant or implausible as it might once have appeared.

Amid the extreme present-tense tunnel vision of American politics and its focus on aggrieved identity groups, it may sound bizarre to conjure up antique and picturesque images of Cockney street urchins and silk-hatted textile tycoons. We have been conditioned to understand politics as a constricted set of binary oppositions whose terms have been stripped of the meanings they once held -- Democrats and Republicans, conservatives and liberals -- boiled down into the daily outrage war between Fox News and MSNBC. Or we put on our thinking caps and conceptualize politics more subtly, as a clash of cultural values and historical interpretations: The coastal cities vs. the exurban heartland; a crusade to overcome America’s story of racism and injustice vs. a national mythology of glorious and divine purpose.

Those dichotomies still have meaning, and intersect with the economic power struggle in many ways. You can never boil any ideological combat down to a single cause, and I’m not defaulting to the “vulgar Marxist” position that class conflict defines everything in society. It took decades of worsening dysfunction and mutual incomprehension for the American left and the American right – accepting those terms of art, for the moment – to reach their current poisonous stalemate, and many factors are implicated on both sides. But the seemingly unrecognizable Victorian age, with its all-white urban slums and its overnight industrial fortunes, is far more relevant to our own time than is obvious on the surface, and retains a nostalgic and ideological resonance for the forces of plutocracy.

No period of recorded history made possible the accumulation of so much wealth so quickly, or represented a purer laboratory to experiment with the operations of unfettered and unregulated capitalism. As Marx documented in hair-raising fashion in Chapter 10 of “Capital,” the early 19th century saw industrial wages driven down to the level of bare subsistence, while the advent of gaslight and then electricity stretched the working day deep into the hours of darkness, beyond any limits imagined by the most ruthless feudal aristocrat. (Even the divine right of kings, he observes, could not compel medieval peasants to work after the sun went down.) Profit became the object of stringent mathematical analysis for the first time, and Victorian capitalism learned to maximize profit – or “surplus labor,” the work an employee performs after covering the cost of her own continued existence – with magnificent precision and endless ingenuity.

But there’s more to the allure of the Victorian era, and the renewed class war of the 21st century, than unmitigated greed. Class interests shape ideology, and ideology shapes class interests. I’m inclined to think that the Kochs and their political hobby-horses are not entirely hypocritical, or at least that they genuinely believe the path to renewed American greatness lies in unregulated profit-taking and the political defeat and disempowerment of the working class. All that wealth that was so rapidly created by driving the laboring people of the British Isles into such spectacular misery – by working 7-year-old children 16 hours a day, in numerous documented instances -- fueled the rise of a mighty industrial economy, and a globe-spanning empire.

This is where the belligerent foreign-policy stance of Cotton and other Republican radicals, and their naked yearning for war with Iran and an expanded American military presence around the world, dovetails with their Mr. Bumble approach to the ungrateful and undeserving poor. They believe that a nation ruled by the rich – by the very, very rich – is a great and powerful nation, and that in the long run the lower orders will be better off if they do as they’re told. It’s a contradictory blend of macho fantasy, discredited supply-side economics and wishful thinking, which reveals all their rhetoric of fiscal responsibility as utter bullshit (as, in fact, a pretext for class war). But through it all runs a strong current of neo-Victorian and neo-Calvinist morality, and a confused nostalgia for the fixed social hierarchies and uncontested global dominance of the British Empire. Why should we wonder (they ask) at America’s declining superpower status? We have surrendered our moral fiber to minimum-wage laws and environmental regulations and the $121 a month in food-stamp benefits provided to Tom Cotton’s poorest Arkansas constituents.

Big Capital’s mission to remake America through renewed class war is far from complete, and there is no near-term version of reality in which Cotton and Cruz live out their wild fantasies of repealing Obamacare, killing food stamps, privatizing Medicare and Social Security, and all the rest of it. But if I had told you a few years ago that public-sector unions would be eviscerated across a wide swath of the labor-friendly Midwest, that would have sounded outrageous too. Inch by inch, the stealth strategy of the Koch brothers is winning a war that most Americans don’t even recognize as a war, between classes we no longer see as classes. In the greatest victory of all, Marx's history-making proletariat has been broken down by the scrubbing bubbles of class-war ideology into millions of individual "consumers," who all happen to have low-wage, non-union jobs in the service sector. Only one side is fighting the class war; the other has been persuaded that no war is even possible, and therefore it must surrender.

Shares