Another day another dinner. Tonight’s session takes place at Food Market in Hamden. The guys who invited me represent the new Baltimore, which is full of new people, new shops and new restaurants. They wanted to talk about ways I can help them understand Black Baltimore — or what’s left of it.

My recent collection of Baltimore writings and talks has made me the go-to guy on issues concerning the Negro culture of our city. Politicians, investors and pretty much anyone with an interest in Baltimore request meetings with me weekly. In most of them, I trade my perspectives for potential opportunities at pricey restaurants I don’t normally frequent.

Suit No. 1, who explained to me in his initial email that he was a lawyer with experience working with artists, said, “This city is a gem. People here don’t even know what they have!” He’s new to Baltimore, so I didn’t expect him to know what “the people” love and value. I let him speak as Suit No. 2 nodded in affirmation.

Suit No. 2 signaled for another round. The restaurant was as packed as it was beautiful. Suit No. 1 and No. 2 look alike. Their faces weren’t similar but their dark-rimmed frames, dress code and personalities were identical – two know-it-all, middle-aged white dudes who probably jogged daily so they could fit into their tight sport coats. I was a sore thumb in Food Market that night — the only patron in a hoodie and sneakers.

The server handed us fancy drinks, and I downed mine before he could refill his tray with our empty glasses.

“One more please,” I said.

Suit No. 2 says he’s a developer, says he wants to help the city, says he isn’t from Baltimore either but he loves Baltimore. He loves Baltimore so much – so much that he’s willing to fix it! He said that he could grow to love Baltimore as much as I do!

$13 cocktails tend to disappear quicker than cotton candy in a hot mouth on a night like this. “You know what,” I say, pulling up my chair, drawing the duel in closer, “I don’t really know if I still love Baltimore.”

Their eyes grew. You would’ve thought I just pulled my dick out.

Suit No. 1 turned glossy-eyed. “Your writing is how I found out about you. You are a gifted Baltimore writer. How could you not love this place, man? How?”

“Gentri-fuckin-cation,” I say. “Gentri-fuckin-cation is why I don’t know.”

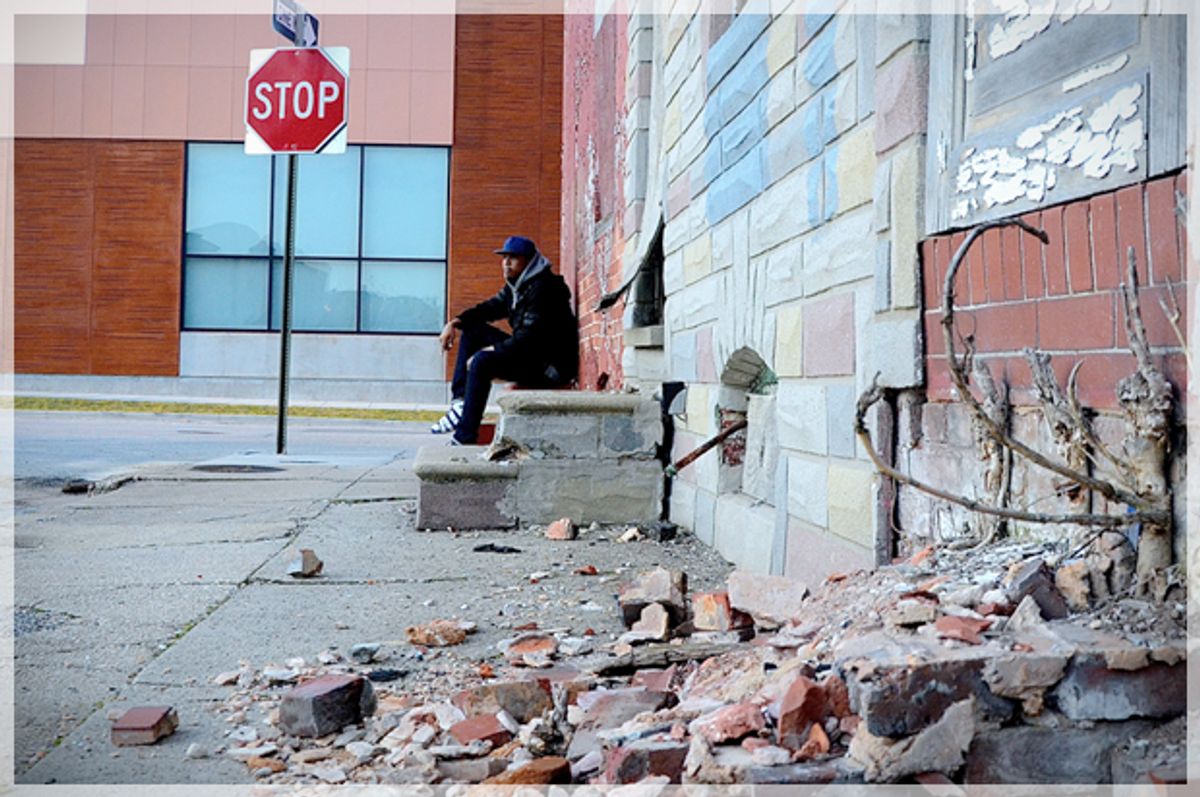

My city is gone, my history depleted, ruined and undocumented. I don’t know this new Baltimore, it’s alien to me. Baltimore is Brooklyn and D.C. now. No, Baltimore is Chicago or New Orleans or any place where yuppie interests make black neighborhoods shrink like washed sweaters. A place where black history is bulldozed and replaced with Starbucks, Chipotles and Dog Parks.

I used to hang in Lafayette Housing Projects with my big cousin Damon. He taught me how to shoot a jump shot, impress a girl without talking and land a left hook. That place is gone. Visiting his old unit after his murder would’ve been therapeutically nostalgic for me but that place is gone and will never be back again.

And when the weather broke back in high school, my classmates and I would cut class over Somerset courts. Pooh Bear, the best baller from the neighborhood, would be knocking down jump shots from half-court on a broken rim and I swear, I swear, I swear he rarely missed. He had everybody in the hood trying to shoot like him. We’d drop our backpacks by the gate and argue during the pickup games we played until well after the sunset. Some of those arguments turned into silly fights that we quickly resolved over marijuana sticks. I’d love to walk through Somerset right now and run a 3 on 3 for old-time's sake but that place is gone. It’s a blank field, the residents are scattered like memories we once shared.

The drink made suit No. 1 sweat a little, but he was trooper, he wanted to do another one, “Deeeee,” he says, “new development brings new opportunity!”

“For who?” I said, a little too loud.

Really for who, who I wonder? Last summer I drove down Wolfe Street and pulled over by Eager. We called this Deakyland back in the day. Most of the earned scratches and bruises I have came from here. We used to break day at that bar High Hats that used to sit on the corner, 2Pac ripped out of speakers while our plastic cups overflowed with Hennessy ––the manager Big Harold had to drag us out at 4 a.m. In between the hangovers and brawls were lessons on life, leadership and brotherhood. We did stupid things but that was our community, the place where our social networks were birthed and then quickly dismantled. That whole block is gone. I realized that I may never see any of those people from that place again as 10 shirtless white guys played two-hand-touch football in a fresh park that they would never build for us -- a huge Johns Hopkins logo was the backdrop.

Suit No. 2 told me that he understands exactly where I’m coming from and can see why I feel the way I do. I asked him if he could go back to the place that holds most of the magical moments from his childhood. He said, “Yeah, my old bedroom is still the same at my folks' place.”

“Then you probably don’t know how I feel,” I replied. “I’m lost in this city. This isn’t the place I grew up in. Corporate dollars are cleansing this city of everything I loved. I will always love Baltimore, the Baltimore I grew up in. I don’t know what this new place is or even if it has opportunity for me. I honestly don’t even know if I should be eating here with you or down SOS on the eastside with my remaining friends. Look around. Do I really look like I belong in here?”

I understand that those now-demolished neighborhoods came with murder, pain, heartbreak, high teen pregnancy rates, illiteracy, gang violence and a host of other reasons that led to their implosions. I also understand that all of these issues stem from lack of opportunity. However, I don’t understand why every black resident must be displaced as soon as opportunity rides the gentrification train into town.

After five minutes of awkward silence we exchanged handshakes, business cards and “Nice meeting you's,” before exiting.

I drove through the city after our meeting thinking about how much I hate meetings, thinking about the new Baltimore, and wondering if my voice is even needed here anymore. I do love Baltimore but it’s becoming a place for the rich and I don’t speak their language. I passed more and more new construction before pulling up on President Street.

A wiry kid ran up to my window waving a squeegee stick just like my friends and I used to do back in the day. I rejected the wash, gave him $5 and said, “Aye shorty keep pushing, this will all make sense some day.” He thanked me and nodded in agreement.

I wasn’t sure if I was talking to him or myself.

Shares