It’s hard to believe that the United States’ vast prison archipelago, holding roughly 2.2 million human beings in cages, somehow squares with the constitutional prohibition on “cruel and unusual punishment.” To many eyes, it is both of those things: The system is fueled by statutes prescribing long sentences that are both extreme and by comparison odd for crimes minor and major.

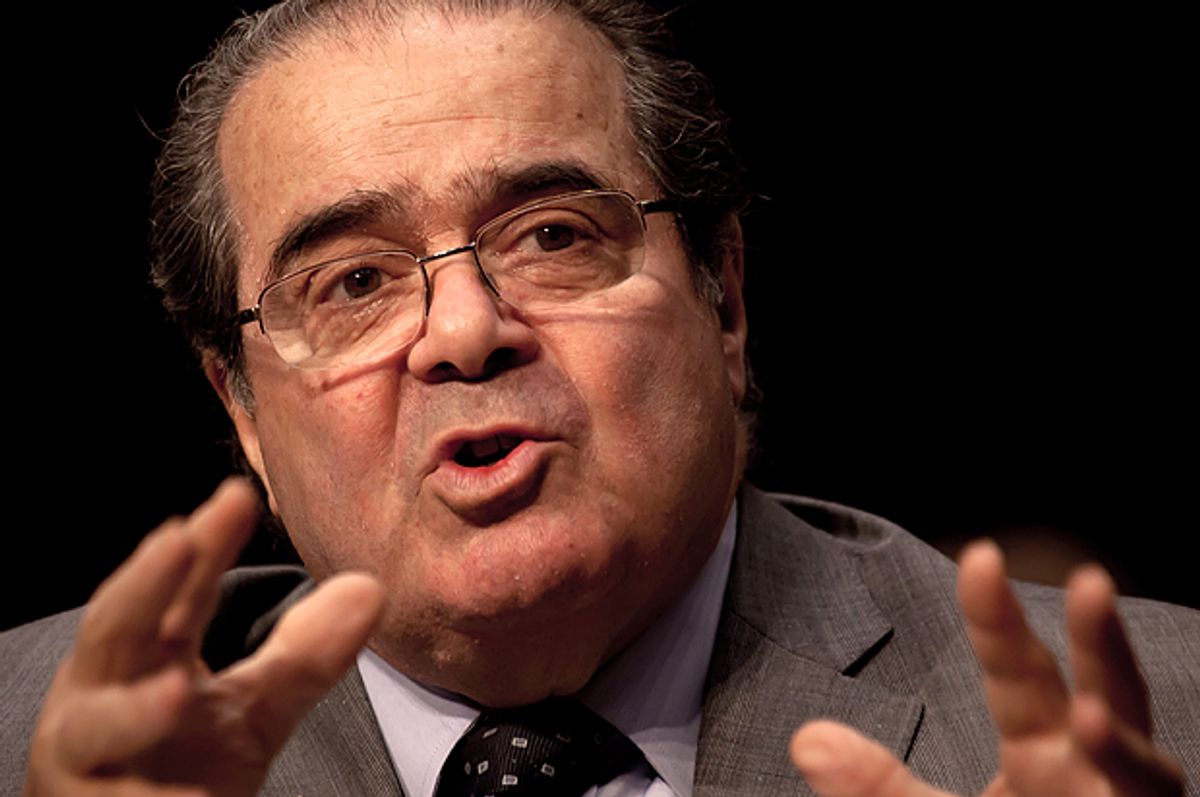

But narrow majorities on the Supreme Court led by recently-deceased Justice Antonin Scalia haven’t seen it that way. Scalia, reaching back to the 18th century as he liked to do, pushed the Court to adopt a maximally restrictive view of what kind of punishment could be so grossly disproportionate so as to run afoul of the Constitution. In practice, he found nothing that would qualify. Replacing Scalia with a more humane, less hidebound justice could allow the Court to take a more expansive look at the Eighth Amendment and, in doing so, do something quite radical: help end mass incarceration. In could also end the death penalty, something that Justices Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg have strongly suggested they are ready to do.

“Scalia was perhaps the strongest opponent of proportionality analysis of any kind under the Amendment,” emails Jonathan Simon, a University of California Berkeley law professor and faculty director of its Center for the Study of Law and Society. “A more robust proportionality rule would go a long way to eliminating some outsized determinate sentences that drive a big part of mass incarceration.”

It was in 2003 that the Court finally shut the door on judicially limiting disproportionately harsh sentences. The case was Ewing v. California, and the matter at hand concerned Gary Ewing, a drug addict and habitual offender with full-blown AIDS sentenced to 25-years-to-life under California’s “Three Strikes” law for stealing three gulf clubs. The Court upheld the conviction but without a majority opinion.

In 1983’s Solem v. Helm, the Court had approached the proportionality of sentences with a slightly more open mind, reversing a life sentence handed down to a recidivist offender for passing a $100 bad check. Justice Lewis Powell, writing for the majority, found that “that his sentence is significantly disproportionate to his crime, and is therefore prohibited by the Eighth Amendment.”

But by 1991, the Court put an end to their flirtation with checking excessive punishment, voting in Harmelin v. Michigan to uphold Ronald Harmelin’s state mandatory life without parole sentence for possessing 672 grams of cocaine. Scalia, writing for himself and Chief Justice William Rehnquist, found that “the Eighth Amendment contains no proportionality guarantee” because while “disproportionate punishment can perhaps always be considered ‘cruel,’ but it will not always be (as the text also requires) ‘unusual.’”

In dissent, Justice Thurgood Marshall went farther than his fellow dissenters, arguing that the Eighth Amendment barred not only disproportionate prison sentences but also the death penalty, finding that “a mandatory sentence of life imprisonment without the possibility of parole does share one important characteristic of a death sentence: The offender will never regain his freedom. Because such a sentence does not even purport to serve a rehabilitative function, the sentence must rest on a rational determination that the punished” conduct is so horrible that the interest in deterrence and retribution outweigh any possibility of reform and rehabilitation.

Breyer and Ginsburg, who dissented in Ewing, are on the court today, and Sotomayor and Kagan could very well join them in finding excess sentences to be unconstitutional. Critically, Justice Anthony Kennedy has come along as well—to a point. Most importantly, Kennedy has joined the Court’s liberals in majority opinions finding that the death penalty is unconstitutional for crimes committed by minors and (along with Chief Justice John Roberts) that mandatory life without parole for minors was as well. The Court has also found the death penalty for rape unconstitutional.

The big question is whether justices would be willing to take the huge and complicated step of determining that excessive sentences for adults and non-death sentences are wrong as well. Right now, the death penalty and juvenile offenders have been carved out as narrow exceptions.

“The areas in which we might see the greatest effect are in the context of life without parole and the constitutionality of the death penalty itself and the procedures used to carry it out,” emails Meghan J. Ryan, Associate Professor of Law at Southern Methodist University. “With respect to life without parole, it is possible that the Court could strike down the imposition of the sentence for certain classes of non-homicide offenders—such as those who are intellectually disabled or suffering from mental illness—or for all non-homicide offenders.”

Simon, however, isn’t optimistic that the Court would embrace a proportionality doctrine to the extent necessary to have a major impact on mass incarceration. But he does believe that other rulings grounded in the Eighth Amendment could. Simon believes that, for example, the Court could overrule the 1981 decision in Rhodes v. Chapman finding double celling unconstitutional, which “would have stopped mass incarceration” from taking off. That year, Justice Marshall lodged the sole dissenting vote.

“With the rising crime rates of recent years, there has been an alarming tendency toward a simplistic penological philosophy that if we lock the prison doors and throw away the keys, our streets will somehow be safe,” wrote Marshall. “In the current climate, it is unrealistic to expect legislators to care whether the prisons are overcrowded or harmful to inmate health. It is at that point - when conditions are deplorable and the political process offers no redress - that the federal courts are required by the Constitution to play a role.”

Simon points to the 2011 decision Brown v. Plata, where the Court ruled that California’s overcrowded prisons were unconstitutional, pushing a recalcitrant state toward some measure of decarceration. Predictably, Scalia called the ruling “outrageous” in his dissent. By contrast, Justice Kennedy’s majority decision indicated the Court’s growing willingness to consider even those duly convicted of a crime to nonetheless remain human beings.

“Prisoners retain the essence of human dignity inherent in all persons,” Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion. “Respect for that dignity animates the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.”

An additional justice who understands this, and maybe even a bit more expansively than Kennedy, could usher in a sea change in Eighth Amendment jurisprudence—one that could put a huge dent in mass incarceration. A fair look of the harsh sentences that hundreds of thousands of Americans currently serve makes it clear that the system is no doubt both cruel and unusual. To end mass incarceration, the Court needs another Justice Marhsall.

Shares