On Wednesday night I attended the huge Bernie Sanders rally in Washington Square Park in Manhattan, where thousands of people crammed themselves into that historic quadrangle to hear the hoarse-voiced Vermont senator give the same speech he has given hundreds of times now. According to the Sanders campaign, 27,000 people turned out — roughly equivalent to a mid-sized Yankee Stadium crowd — and that doesn’t sound implausible. From where I was standing near the western edge of the park, Sanders himself was an illuminated matchstick figure, nearly a quarter-mile away. Spike Lee and Rosario Dawson and Tim Robbins warmed up the crowd, along with officials from the Communications Workers of America (currently on strike against Verizon) and the New York transit workers union, two large and diverse labor groups that have recently endorsed Sanders.

People like me should have learned by now to be cautious about declaring a high-water mark to the Sanders campaign, since to Hillary Clinton’s chagrin it has proved unquenchable to this point. Clinton is clearly still favored in Tuesday’s decisive New York primary, but the polls have tightened noticeably, and the support of two activist unions that reach deep into the city’s African-American and Latino communities may make the race tighter still. Moving through the crowd, I was struck once again by what I first noticed in New Hampshire: Hillary Clinton is a political candidate; Bernie Sanders has galvanized a mass movement. As Clinton’s supporters will tell you, she has attracted more votes than Sanders, and may well do so again on Tuesday. But could she pull a crowd of 27,000 in Washington Square? She wouldn’t even try. Sanders represents the emergence of something that goes beyond winning or losing elections, a collective awareness that once upon a time would have been called “class consciousness.”

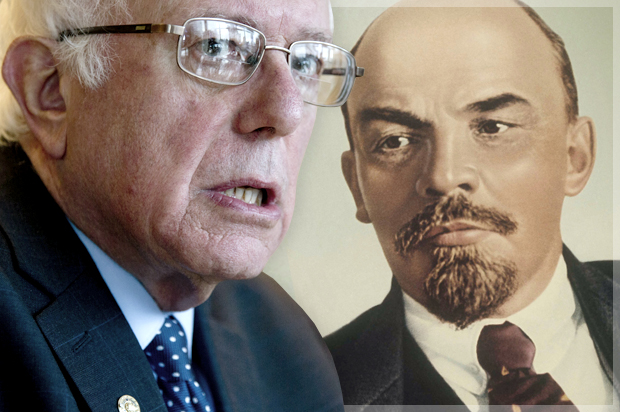

This may be widely misinterpreted, and may land me a slot on Fox News, but I’m going to say it anyway: The split between Sanders and Clinton within the Democratic Party — or let’s say the “Democratic coalition,” since political parties are rapidly becoming irrelevant — is like a distorted mirror-image of the legendary split between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks, roughly 110 years ago, that preceded the Russian Revolution. Wait, hang on: I’m not saying that Bernie Sanders is a Lenin-in-waiting, or that he covertly supports the confiscation of all private wealth and property. (Can we pause a moment to acknowledge the remarkable fact that someone who did support those things might actually get votes in 2016?)

In political terms, both Sanders and Clinton are Mensheviks at most (the ancestors of modern European social democrats, more or less), and not the most adventurous among them. Those Democratic loyalists who emphasize that the two candidates aren’t far apart on many issues, and that the difference between them is mostly a matter of symbolism and semantics, are partly right. But they fail to appreciate how deep that symbolic divide goes, and how much meaning it carries. The Bolsheviks and Mensheviks both wanted to “build socialism,” but one group went into parliamentary politics forever while the other overthrew the Romanov dynasty and then liberal democracy and tried to establish the “dictatorship of the proletariat.” Neither experiment worked out exactly as intended, but that would be an extremely long tangent.

What I mean is that the division between Clinton and Sanders represents exactly the same ideological conflict, in the same form: How do we engage with a corrupt political and economic system that is showing signs of terminal decline? This is of course the political and strategic division between reform and revolution, a conflict which the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (as it was then called) did not invent, and which has long outlasted it. On one hand, we find the idea that progressive change requires working within the ideological system that surrounds us, and the political and economic institutions it has enabled — either because those things represent an unalterable reality, or because we conclude that they cannot be changed right now, or because they are good and just and right.

Hillary Clinton has seemingly embraced all three of those perspectives at various times and before various audiences: My hunch about her Goldman Sachs speeches is that the problem is less whatever substantive arguments she made to the Wall Street overlords than how she framed them. In any event, Clinton clearly represents the Democratic Party establishment as it was reshaped under her husband, which has irrevocably allied itself with neoliberal economics, finance capital, globalized free trade and the entire pseudo-imperialist military-industrial package sometimes called the “Washington consensus.” She didn’t know that those things would suddenly and inexplicably (in her view) become unpopular with much of the supposed Democratic base, and she could not plausibly pose as a spokesperson for revolutionary paradigm shift if she wanted to. (In fairness, she doesn’t want to.)

Bernie Sanders’ repeated use of the term “revolution” is in some sense metaphorical, and in another sense conflicted or confusing. But it’s also deliberate: He is invoking the revolutionary tradition of the last three centuries, with its entire range of associations, without quite explaining what he means. He always says “political revolution,” to make clear that he doesn’t mean the kind of revolution that involves blowing up the old regime’s monuments and hanging its leaders from the lampposts. But what does he mean? Sanders’ specific proposals really don’t merit that term: Single-payer healthcare, free higher education for all, tighter regulation of financial markets and higher wages for working people all are, or were, mainstream positions within the recent history of Western politics.

Sanders is advocating a wide-ranging package of political and economic reforms, to be sure, but nothing that comes close to the overthrow of our political institutions or the widespread seizure of capital. But to get from here to there, in the context of 21st-century America, requires a revolutionary shift in consciousness. Sanders speaks to, and speaks for, a large group of people who have arrived with unexpected rapidity at a consciousness of their own exploitation, and even their “immiseration,” to use a Marxist-Leninist term. They see the global economic and financial system produced by neoliberal fiscal policies and “free trade” as a massive con game designed to steal from the poor and give to the rich. They see the bipartisan political system of the United States as paralyzed, poisoned and all but powerless.

Such a shift in consciousness is correctly perceived as dangerous by the elites behind our political parties and our economic system, but those are also difficult ideas to argue directly against, amid the chaos of 2016. (Jeb Bush took that line, with all the money in the world behind him, and look what happened.) After his own bizarre fashion, Donald Trump also represents a radical shift in consciousness, although from your perspective and mine it may look like a delusional shift toward a false consciousness. When Sanders suggests, sometimes by implication and sometimes directly, that the fundamental ideological precepts that have governed our social, economic and political lives since the Reagan era must be overthrown, that is indeed a call for revolution. Hillary Clinton has always been an amorphous politician leery of ideological labeling, but at her most effective moments of this campaign she has positioned herself as the decaf Bernie, a not-quite-revolutionary armed with less strident rhetoric, less radical proposals and a greater ability to get things done.

I’ve been struggling through a recent revisionist biography called “Reconstructing Lenin,” by the Hungarian academic Tamás Krausz, which strives to rescue at least some of the Soviet founder’s political and philosophical insights from the long hangover of his failed state. It’s a fascinating account with many points of surprising contemporary relevance, especially if you skip over the lengthy expositions of arcane debates within Marxist theory. (Despite his best efforts, Krausz can do little to change the perception that Lenin was a thin-skinned, arrogant jerk.)

For all the enormous differences between early 20th-century Russia and early 21st-century America — not least the near-total disappearance of the “industrial proletariat,” at least as Lenin understood it — it strikes me that Lenin would have grasped the dynamics (or the dialectics) of the American left’s current dilemma immediately. He was a shrewd and pragmatic tactician who spent much of his career navigating between strategies of reform and revolution, and grappling with the distance between incremental progress and ultimate goals. He was constantly bedeviled by the mysterious nature of “revolutionary class consciousness,” which appeared first and strongest among relatively privileged groups — the students and the intellectuals and what we would today call the downwardly mobile middle class — and only took hold later or not at all among the workers who stood to benefit most. Does any of that sound familiar?

Lenin applied some of his most vicious rhetoric to the “foulness” of the kind of “bourgeois liberalism” that opportunistically attached itself to the fringes of the socialist movement, preaching the “renunciation of the class struggle” and the politics of “peace with the slave-owners.” He hated such “class traitors” who undermined the cause of revolution more than he hated monarchists and right-wingers, who at least did not conceal their true motives. It’s almost hilariously similar to some of the exaggerated bile directed at Hillary Clinton, and in both cases the question of who was right and who was wrong defies any easy answer. As for those who feel sure that the revolutionary shift in consciousness revealed or channeled by Bernie Sanders is a transitory fad that will soon be swept aside, and that true social progress demands long and difficult work within existing political institutions, however diseased and dysfunctional they have become — those people could be right. At least for now. That’s what the Mensheviks of 1907 thought too.