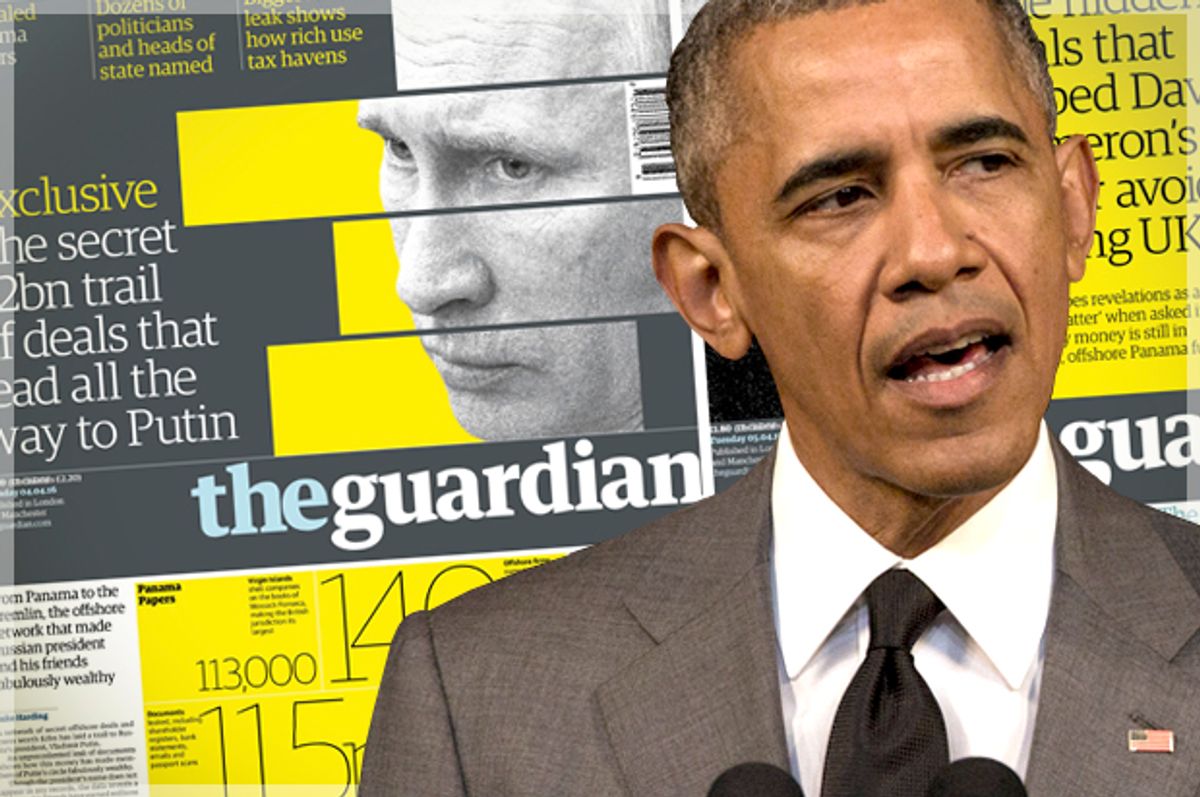

The Obama Administration didn’t wait for yesterday’s release of over 200,000 offshore companies implicated in the Panama Papers investigation to respond to ongoing revelations of routine tax avoidance by wealthy individuals. Last week, they announced a suite of new rules to combat tax evasion and money laundering through anonymous shell corporations, and pressured Congress to go even further.

In theory, more disclosure and transparency makes sense. But experts who have urged action on tax avoidance for years say that the Administration’s efforts not only fall short, they could be actively harmful to the cause.

The White House fact sheet explains that the Treasury Department finalized one rule and proposed another. The “Customer Due Diligence” final rule, first proposed in 2012, requires financial institutions to keep records on the beneficial owners who “own, control, and profit from” all corporations that have accounts with them. They must verify the identities of these beneficial owners in some fashion, and conduct ongoing monitoring of the accounts. Under the Bank Secrecy Act, this information would be available to law enforcement, allowing them to more easily track compliance with sanctions programs and shut down any illegal flow of money.

A second regulation forces foreign-owned limited liability corporations (LLCs) to apply with the Internal Revenue Service for an employer identification number. The Administration believes this will give the IRS more tools to identify tax avoidance or money laundering.

The problem, as always, comes in the details, which experts say include key loopholes. Under the final Customer Due Diligence rule, the beneficial owner could be listed as the agent who manages the shell corporation, rather than the ones who own it. Under this definition, the “beneficial owner” could be a designated manager, like a lawyer at Mossack Fonseca, the company at the heart of the Panama Papers leaks who set up hundreds of thousands of shell companies for their clients. This would be of no use whatsoever to law enforcement in cracking down on the true beneficiary, the individuals profiting from the shell corporation setup.

Elise Bean, who used to run the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations under Carl Levin, where she authored several exposés on tax evasion and money laundering, says this corrupts the definition of beneficial ownership as it has been commonly used. It also releases pressure on banks, which actually have begun to obtain real beneficial ownership information over the past several years. “Many U.S. banks have done the hard work involved with developing systems that verify the true owners of shell companies seeking to open accounts,” Bean said in a statement. “The new rule makes all that hard work irrelevant. It is a mistake that needs to be fixed.”

In addition, the final rule places a threshold in their definition of legal ownership of 25 percent equity interest in the corporation. Experts believe this provides would-be money launderers with a blueprint for how to avoid detection by diffusing their ownership stakes through multiple beneficiaries. In addition, accounts set up in escrow by lawyers are excluded from the provisions. Global Witness performed an investigation earlier this year, which appeared on "60 Minutes," featuring lawyers who assist wealthy individuals in setting up anonymous shell corporations. And at least one of them suggested escrow accounts as a means to avoid oversight, showing that this loophole is ready-made for abuse.

The Treasury Department rejected criticism about downgrading the beneficial ownership definition to managerial control, but they did not comment on these other loopholes, nor did they explain why they extended the timeline for the rule to take effect from one to two years.

In another development, the White House called on Congress to act on legislation requiring companies themselves, not the financial institutions they use, to report the beneficial owner. In a letter to Congressional leaders, Treasury Secretary Jack Lew asked them to “build on Treasury’s action by requiring companies to know and disclose the real person behind a company at the time of its creation.”

But this legislation already exists. The Incorporation Transparency and Law Enforcement Assistance Act, which has bipartisan sponsors in the House, would do everything the White House claims to want, requiring states and the Treasury Department to collect beneficial ownership information at the time of incorporation, and make that information available to law enforcement. It’s unclear why the Administration would need to re-write what already has been written, and since they’ve released nothing official about their own draft legislation, it creates suspicions that they are trying to undermine the current effort in Congress, with analogous flaws to the Treasury rule.

Finally, the Administration used the announcement to take a victory lap on all their wonderful global leadership in cracking down on illicit financial activity. This has things almost exactly backwards. Because the United States is one of the only developed nations that doesn’t automatically reciprocate the release of tax information with other countries, it has become “the new Switzerland,” the place the world’s wealthy come to hide their money.

This isn’t entirely the Administration’s fault – Congress can shoulder some of the blame for failing to require states to collect data on corporations they register – but the cheerleading in the face of becoming a leading global tax haven is a bit gross. For instance, the fact sheet boasts that the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act, passed by Congress in 2010, “is the template for the development of international standards” instituted by international authorities. But the U.S. hasn’t signed onto those international standards. In his letter, Treasury Secretary Lew says signing on would require an act of Congress, a typical refuge for the Administration to get out of doing anything remotely controversial.

Last week, the whistleblower who provided the documents in the Panama Papers case released a personal manifesto, calling on the nations of the world to “put an end to the global abuse of corporate registers.” He points the finger at Congress, and their inability to implement standards while the wealthy who want to keep their tax havens ply them with campaign contributions. But while the whole political system has failed to prevent this two-tiered system of tax compliance, the Obama Administration shouldn’t be let off the hook.

Shares