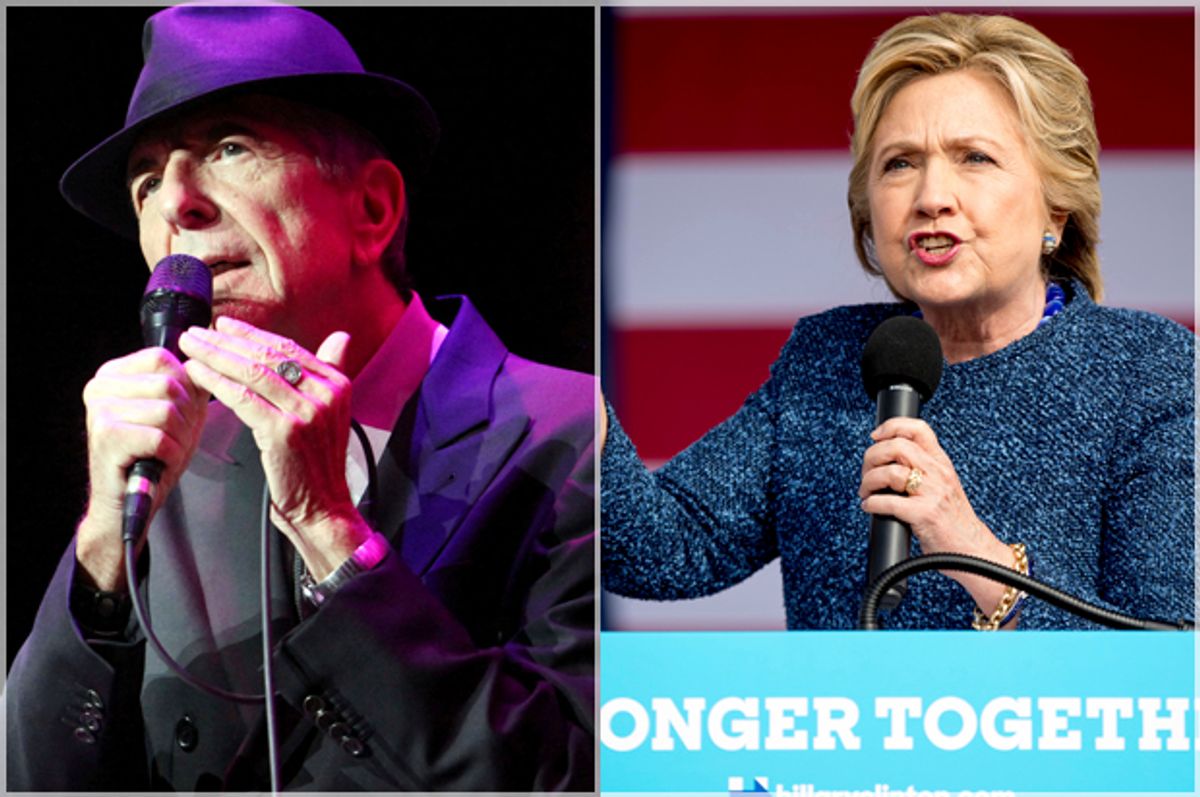

“Everybody knows the war is over/ Everybody knows the good guys lost,” sang Leonard Cohen almost 25 years ago, when he and the rest of us were a good deal younger. I’m getting to the aftermath of the Trump election and the current predicament of the Democratic Party, I promise. This is an important detour along the way.

Everybody knows the fight was fixed

The poor stay poor, the rich get rich

That’s how it goes, everybody knowsEverybody knows the boat is leaking

Everybody knows the captain lied

Everybody got this broken feeling

Like their father or their dog just died

Everybody's talking to their pockets

Everybody wants a box of chocolates

And a long-stemmed rose

Everybody knows

I don’t know how much attention the great Canadian troubadour paid to current events during his final days in this vale of tears. I can only imagine he was both horrified and mordantly amused by the rise of Donald Trump, a cartoonish would-be despot who seemed to have been conjured out of Cohen’s darker visions. (I have no particular objection to Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize, except one: Leonard Cohen deserved it more.) All those disgruntled and downtrodden white people we’ve heard so much about apparently felt that everybody besides them had gotten a box of chocolates and a long-stemmed rose. So they ordered their own — and boy howdy, did they ever get them! Now, it’s true that the chocolates have a funny smell, almost as if they were made of something else that’s about the same color as chocolate. And the delivery guy bears a distinct resemblance to Freddy Krueger. As Cohen observed, that’s how it goes.

In the title song of Cohen’s now-classic 1992 album “The Future,” he outlined a litany of terror-nostalgia that captures our present era even better than it did that one: “Give me back the Berlin Wall/ Give me Stalin and St. Paul/ Give me Christ or give me Hiroshima.” I think he really was a Jewish prophet (turned Buddhist monk) who could see the future. That human yearning for moral certainty and clarity, even at the risk of extinguishment or fiery damnation, runs through Cohen’s lyrics. There is a great deal of that spirit behind the unlikely election of a real estate tycoon and TV star, who possesses no understanding of policy or governance and no aptitude for public discourse, as president of the United States.

Few media phenomena are more obnoxious than a pundit who says, “I told you so.” I didn’t exactly do that. The writing was on the wall, but like the rest of us, I couldn’t quite decipher it. I have suggested at various times during the endless 2016 presidential campaign that Hillary Clinton’s candidacy was surrounded by “a cloud of doubt and uncertainty” that seemed impossible to dispel, and that she was in danger of being “sideswiped once again by an unlikely outsider riding the train of history.”

That was in September of 2015, and of course I was referring to Bernie Sanders (or at least I thought I was), not to the orange humanoid who is now the president-elect. That’s how it goes. In the same column, I suggested that Hillary Clinton’s anxious supporters, her left-wing critics and her right-wing persecutors all suffered from different strains of a disorder I called “Hillary panic”:

Those beliefs are effectively … the same deep-rooted sense that no one anywhere on the political spectrum is all that comfortable with Hillary Clinton, and that the more closely people look at her, the less inclined they will be to elect her president. You can argue that this is untrue or unproven, and you can say that it’s not really Clinton’s fault, and that Hillary panic is a product of tide and circumstance. But the perception is widespread. Through her husband, she is tied to an era of weathervane politics and a strategy of centrist triangulation and Republicrat appeasement that produced all kinds of noxious consequences – from the mass incarceration of African-American men for drug offenses to the financial collapse of 2008 — and is viewed by progressives with justifiable distaste or worse. Any hint of scandal flung at her, no matter how irrelevant, conjures up unwanted memories of the scandal that destroyed her husband’s presidency. No Republican needs to mention the name of “that woman” or bring up the stained dress, but those images lurk out there on the fringes of collective consciousness.

Clinton, I suggested, was a highly qualified presidential candidate, “facing a moment when the public feels profoundly alienated from all such things and yearns for stronger coffee, flavored with a dash of socialism or fascism or flat-out insanity.”

Since we’re in the mood for self-recrimination this week, I’m sorry that I predicted the Trump strategy and its outcome so accurately, long before I or anyone else believed that Trump would actually be the Republican nominee. Don’t Steve Bannon and Kellyanne Conway owe me a commission or something? (Based on Trump’s record with vendors and subcontractors, the check wouldn’t clear anyway.)

After the traumatic experience of sitting through Trump’s acceptance speech at the Republican convention in Cleveland last July, I sat up all night and began to entertain the notion that he might actually be elected. But even then it was more like a daring thought experiment, a “what if we lived in a dystopian comic book?” kind of thing. But the comic book began to take shape around us. Michael Moore told us repeatedly that Trump was going to win, but that seemed like a rhetorical exercise, intended to get Democrats off the couch on Election Day. Allan Lichtman of American University, whose predictive model had successfully gamed out every presidential election since 1984, told us that Trump would win — but even Lichtman said that Trump was such an unorthodox and unpredictable candidate he might break the pattern. (Lichtman has also since predicted that Trump will be impeached, so the liberals who hated him a week ago are now big fans.)

Lichtman and Moore were right, and so were those of us who cautioned Democrats not to laugh too loud or too long at the Trumpian implosion of the Republican Party. We don’t yet know what kind of truce can be forged between the isolationists, anti-immigrant fanatics and far-right populists of the Trump movement and the tax-cutting, corporate-lackey 1-percenters of what used to be the GOP mainstream. But the party has been remade in a violent internal revolt that culminated with a Bolshevik-style seizure of power. So all sides have enormous incentive to work it out, not to mention at least four years of undivided control of the federal government. (Does that sound like I’m ruling out the possibility that Democrats will recapture either the House or Senate in 2018? Yeah, I pretty much am.)

I recognize the need to make ritual pronouncements about how we should wait and see what a Trump presidency will actually be like without rushing to judgment, etc. But let’s keep that good-German stuff to a minimum, shall we? I refer you to Russian-American journalist and Putin biographer Masha Gessen, whose New York Review of Books article “Autocracy: Rules for Survival” is one of the week’s must-reads. Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama’s civil and conciliatory approaches to President-elect Trump, Gessen argues, are based on a series of false assumptions, starting with the assumption that “Trump is prepared to find common ground with his many opponents, respect the institutions of government, and repudiate almost everything he has stood for during the campaign.”

Gessen’s first rule for surviving autocracy is this: “Believe the autocrat. He means what he says. Whenever you hear yourself thinking, or hear others claiming, that he is exaggerating, that is our innate tendency to reach for a rationalization.” In the mid-1930s, she reminds us, the New York Times assured readers that Adolf Hitler’s anti-Semitism was political posturing, and that he did not intend serious harm to the Jewish population. (I would add a footnote: The first half of that may have been true, but the second proposition did not logically follow.)

There is precious little silver lining for the American left in what some alt-right fanboys have joyously termed the “Trumpenkrieg.” But at least it may force a long-delayed moment of reckoning within the Democratic Party and the left-liberal coalition more broadly. Sen. Chuck Schumer, who no doubt had already measured the carpets and ordered the maritime antiques for the Senate majority leader’s office, appears to have made an interesting strategic decision in the wake of the Trumpian catastrophe. Schumer is a close ally of the Clinton family, a pro-Israel military hawk and one of Wall Street’s best friends inside the Beltway. On Thursday he joined with Sen. Elizabeth Warren to endorse Rep. Keith Ellison of Minnesota, one of the most progressive Democrats in the House (and the first Muslim ever elected to Congress), as the next chair of the Democratic National Committee.

I suspect the correct way to interpret this is that both sides in a prospective intra-party conflict — the Hillary Clinton wing and the Bernie Sanders wing, effectively, although neither of those people is likely to play a leadership role into the future — have agreed to postpone the ideological showdown for another time. With the midterm election still two years off and the Clintonite forces simultaneously tarnished by scandal and reeling from a humiliating defeat, handing over the party leadership to the activist crowd, at least for now, will serve as a way of calming internal tensions and presenting an image of unity.

I don’t think this apparent peace treaty means that the Democratic establishment represented by Donna Brazile and Debbie Wasserman Schultz and Schumer has capitulated in any meaningful way, or that we can assume that Elizabeth Warren, or someone else in her mold, is now the likely frontrunner for the 2020 nomination. There’s already considerable chatter among Democratic loyalists to the effect that nothing is fundamentally wrong with the party in terms of principles or issues or organization or anything else. Since Clinton apparently won the popular vote (this line of thinking holds), Trump’s razor-thin Rust Belt victory was nothing more than an unfortunate fluke of the electoral system in a narrowly divided nation. The polls were right! Clinton actually won! Except for the minor inconvenient fact that she didn't, under the rules known to all parties in advance, and that someone else (or something else) will take the oath of office in January.

This fluke, a cynical observer might respond, follows a long series of other, similar flukes, from the Tea Party wave of 2010 to the massive midterm wipeout of 2014 and the Republican conquest of most state legislatures and most state elective offices between the Eastern seaboard and the Sierra Nevada mountains. No doubt it’s also a fluke that party affiliation has fallen to historic lows over the last decade or so (for both Democrats and Republicans), and that Hillary Clinton got roughly 6 million fewer votes than Barack Obama did in 2012 — and perhaps 10 million fewer than he did in 2008. (Trump, by contrast, will end up pretty close to Mitt Romney’s 2012 total.)

There’s something to that argument, at least in the narrow technical sense. In an election as close as this one was, any marginal factor could have changed the outcome. If African-American turnout in Detroit, Milwaukee and Philadelphia had been a little better; if only 51 percent of white women had voted for Trump (instead of 53 percent); if Gary Johnson had decided to drop out in the final week; if Republicans had been less successful at drafting onerous voter-identification laws in numerous states — you can draw up your own list of factors that might have led to liberals mopping their brows in relief this week as they celebrated a historic feminist breakthrough.

But continuing to obsess over the marginal, technical aspects of electoral politics — and refusing to discuss whether all the “weathervane politics” and “centrist triangulation” and Wall Street snuggling of the Clinton era were the right politics and the moral politics and even the winning politics, in historical terms — is exactly what got the Democratic Party where it is today. I don’t claim to know whether or not Bernie Sanders could have defeated Trump, and that is now yesterday’s dispute. I don’t claim to know whether Keith Ellison and Elizabeth Warren can inject some grassroots-style passion and fire into a drifting, rudderless party whose energies are largely devoted to engineering its own defeat, time and time again, and then explaining tirelessly that it did the best it could and someone else is to blame. Those doggone voters: So stubborn and so mean!

What I do know is that the Ellison-Warren experiment is worth trying if the Democratic Party is to have a future, and that the larger debate about the political and electoral future of the American left — or rather the overt ideological conflict about that question — cannot be postponed forever. Sometime very soon, Donna Brazile and Chuck Schumer and the rest of the momentarily defeated and disgraced Democratic old guard will begin to reconnoiter and rebrand and build a strategy for the Trump administration and the 2020 election. Can you see Cory Booker over there, warming up his beautiful smile and his anodyne rhetoric, and booking his private meetings with Wall Street executives? Maybe those forces will be proven correct and will win, and the “emerging Democratic majority” promised for two decades and counting will at last sweep Trump and the troglodytes into the dustbin of history. My money’s on Stalin and St. Paul.

Shares