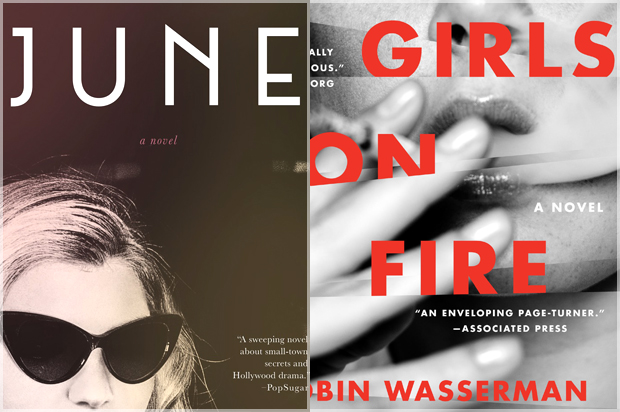

Miranda Beverly-Whittemore’s novel “June” and Robin Wasserman’s novel “Girls on Fire” are set nearly 40 years apart, but both tackle the same central questions of female adolescence and the intense, all-consuming relationships that can swallow teen girls whole. As both books come out in paperback this week, the authors spoke to each other about girlhood past and present, coming of age in small-town America, and their experiences writing about girls and women in a world hostile to both.

Miranda Beverly-Whittemore: Robin, the whole time I was reading about Dex and Lacey, your titular girls on fire, I was thinking about other incendiary girl pairings in books I’ve loved — including in the work of Megan Abbott (whom we both love) — and also the best friends in my own most recent novel, “June.” I’d love to hear how these girls became your story.

Robin Wasserman: Thanks for kicking this off with an easy one! The answer is absurdly simple: These girls became my story because these girls have always been my story.

For whatever reason — maybe because I’m an only child — I was obsessed with having a best friend from the moment I learned there was such a thing. And the “best friends” I collected over my childhood and teen years all fit the same general type: strong-willed girls looking for someone to boss around. It was a pattern I fell into — flung myself into — over and over again. These bright, stubborn, outspoken girls who exuded an energy I couldn’t imagine in myself, who could become not just my defenders, but also my excuse. Sometimes that meant an excuse for timidity — who needed to speak when they could speak for me? But more often, they were an excuse for some wildness of my own. An excuse to unleash the self I kept so carefully buried. These girls offered me plausible deniability: I could tell the world, and more importantly, myself, that whoever I seemed to be, I was only a reflection of the girl by my side.

“Girls on Fire” was born from these friendships and from the years afterward I spent trying to puzzle them out. I knew what I was getting from these girls, but what were they getting from me? What were we generating between the two of us, these new selves that could only exist because someone else believed in them?

I was surprised, when I first read your novel, to discover how much our stories had in common, and the intense, uneven connection between two girls is at the top of this list. “June” is your second novel in a row to tackle this dynamic — in both books, there appears to be a leader and a follower, one with power and one without, but in each, you gradually complicate these relationships so that on any given page neither we nor the girls are quite sure of the ground they’re standing on. Why investigate this kind of friendship? And is the friendship in “June” in conversation with the friendship in “Bittersweet?” Did you end “Bittersweet” with more questions than you began it (as is often the way), and write “June” partly to answer them?

Beverly-Whittemore: When I was writing “Bittersweet,” and people would ask me what it was about (my pat response was “best friends, one plain, one gorgeous; imagine how that turns out”), I was amazed to discover how many women were compelled to speak of a best friendship in their past. These were stories rife with passion, betrayal, heartbreak or need. Most were located in girlhood, and most didn’t have a boy in sight; I was so intrigued that I started a (now defunct) web project called Friendstories.com as a place to collect them. There’s a deep fascination in many of us about a past self that could exist only because someone else believed in her. I think for many girls, pairing up young is excellent practice for surviving the heartbreak, and navigating the rules, of future love affairs.

That’s one big difference between the best friends in “Bittersweet” — Mabel and Ev — and the ones in “June” — Lindie and June. While Mabel has an obsession with Ev’s glamorous lifestyle and seemingly perfect family, she doesn’t want to fuck her, but Lindie lusts for “good girl” June (although since they live in the 1950s in Ohio, she has a hard time naming these natural feelings for what they are). Lindie and June make unexpected sacrifices for each other; since Lindie knows she can’t have June, she does the next best thing, which is to set June up with a man she believes is good enough for her, a man whom June ultimately gives up to save Lindie.

This brings me to the very real subject of sex, and how that plays out in both of our books. How do these friendships change when sex and desire and power enter the mix? And boys, lord, what about the boys?

Wasserman: Earlier this year I found myself on a panel, going on and on (as I tend to do on panels) about how one of the true joys of writing “Girls on Fire” was exploring an adolescent landscape that was — like my own — almost completely unconcerned with boys and sex. I got so wrapped up in this rhapsody that it fell to the moderator to remind me that the novel is actually filled with — or at the very least, revolves narratively around — much sex and at least one boy. (Although in fairness to me, the boy spends most of the book dead.)

It’s not so much that I forgot, it’s that for me, the beating heart of the narrative is the relationship between these two girls to the exclusion of all else. Where sex and desire do enter the mix, it was important to me that it feel, if not secondary to, then continuous and organically emerging from, the friendships. What’s the word for a love that’s not romantic but also not purely platonic, for something so all-consuming it dissolves boundaries of both flesh and selfhood? That’s the space I wanted to inhabit: a friendship between two girls who want to own every piece of each other, who want not just ownership, but inhabitance — to crawl inside each other’s skin. To merge into one.

Beverly-Whittemore: Yes, my sister and I call this an “I want to eat her” friendship. I, too, was a kid who had serial, kindred best friends, from the time I was four through high school (when my best friend put a love note in my locker every single day), and even into college (a friendship that went down in flames, but unexpectedly rose like a phoenix once we became moms). I love how you describe it: “to merge into one,” because that’s really what it does feel like; slipping into a new skin shared with a beloved, a safe space in which you never have to be alone. And yet, it always ends, that era. You end up outgrowing each other, shedding each other, in one way or the other.

Wasserman: For me, that kind of all-consuming adolescent friendship was more aspiration than reality, which may be why I’m fascinated by what happens inside these closed loops — and why I’m equally fascinated by what we make of them from the outside looking in. I have a theory that the reason we see so many cultural examples of “bad girl” friendships (think “Heavenly Creatures”) is because there’s something unsettling, even threatening, to men about an all-female space, one that exists neither for them nor in spite of them, rendering them less excluded than irrelevant. “The Virgin Suicides” does a wonderful job both exploring and instantiating this discomfort, but for me, the most powerful articulation of it is the Steven Millhauser story “The Sisterhood of the Night.” It’s the story of a town whose girls have taken to slipping out at night, meeting secretly in the woods. To do what? In the voice of a concerned citizen, Millhauser writes:

“I submit that the girls band together at night not for the sake of some banal and titillating rite, some easily exposed hidden act, but solely for the sake of withdrawal and silence. The members of the sisterhood wish to be inaccessible. They wish to elude our gaze, to withdraw from investigation — they wish, above all, not to be known…We cannot stop the sisterhood. Fearful of mystery, suspicious of silence, we accuse the members of dark crimes that secretly soothe us — for then will we not know them? For we prefer witchcraft to silence, naked orgies to night stillness.”

By the end of the story, we understand that this silence, this elusion will not stand. Withdrawal is threat, and: “Already there is talk of a band of youths who roam the town at night armed with pointed sticks.”

The assumption that all girls can, will become bad girls in the dark is leveraged to justify an all-penetrating gaze. We must see, to ensure you behave.

But behave how, according to whose standards? I love that you put “good girl” in scare quotes, because your novel so powerfully depicts the consequences of imposing these arbitrary labels. Good, bad; well-behaved, wild. Is that something you set out to tackle from the start?

Beverly-Whittemore: Yes, the externalized notion of a “good” or “bad” girl is a construct of our paternalistic society, no doubt about that. The character of June — obedient, willing to accept what the world hands her, so, in this case, “good” — is not someone I would be particularly drawn to in real life, which might sound funny, since I’ve named a novel after her. Lindie is much more my cup of tea, although she’s much braver and more ornery than I, which means that in 1950s Ohio, she’s “bad.” On the romantic side, Lindie desires June for her goodness, but as a friend, that very goodness is what drives her crazy on June’s behalf. This push and pull became the engine that propels the book, although I didn’t know it until I’d written a large chunk.

I’d love to hear you talk more about Lacey and Dex in the context of the small Pennsylvania town in which they live, and the era in which they come of age. Could the alchemy of their friendship occur in any other place or time? What is it about that specific era and location that shapes them?

Wasserman: “Girls on Fire” is set in 1991-1992, during the Clinton-Bush campaign season, a moment with some unexpected and depressing resonances with our current one. 1992 was known (at least by pundits) as the “Year of the Woman”: four women were elected to the Senate, and 500,000 more descended on D.C. for a pro-choice march — marchers chanted, among other things, “Pro-Clinton, pro-choice.” (La plus ça change…) But if it was a triumphant time for women, it was also a regressive one, rife with backlash. The Clarence Thomas/Anita Hill hearings; the beginnings of the anti-Hillary hate machine; the first shots fired in a culture war still raging today.

Much of this has, unsurprisingly, taken on a new dimension for me in the last few months. (Read: In the age of Trump.) Even the setting, a small town in western Pennsylvania, seems transformed: the fictional town of Battle Creek is positioned at the edge of the Rust Belt, like so many of the towns profiled in this year’s campaign season by perplexed coastal reporters. The novel’s families are the same families that would, over the next decade, be torn apart by a dying economy — and 1992 was, in many ways, the moment those economies took a turn for the terminal. If you read Bill Clinton’s original stump speeches, as I’ve been doing lately, it’s remarkable how similar they are to the economic rhetoric of this election season: promises to stop outsourcing, to keep factories at home, to save American manufacturing, to turn a jobless recovery into an employment boom.

My girls on fire would be 41 this year, and I’ve spent a lot of time since the election thinking about the women they might have grown to be — what they might have come to believe; who they might have come to blame.

As may be obvious, these days I’m reading everything through a lens of my own political rage, including my own book. (The rage was baked in from the start, but it’s risen to the surface for me: what was diffuse is now acute.) I’m curious whether you’ve had the same experience, reconsidering your novel in what feels like a very different world. Are you seeing things in it that you didn’t before — like me, are you surprised to discover how much was already in there, as if the book somehow knew what was coming before we did? And, to shift gears from past to future, are you thinking in a new way about your work, and about what’s coming next?

Beverly-Whittemore: Funny you should ask. I did a reading a few weeks ago, post-election, and mentioned that Lindie is in love with June, and someone lobbed, “don’t you just mean that she admires her?” Immediately, I was lit from within by a very red, angry fire and quipped, through bared teeth, “Nope, she wants to fuck her,” using the word “fuck” mainly for shock value, because I guessed that anyone who would question me on this point would be made uncomfortable by it.

I did not think of this book as political as I wrote it, although, on a fundamental level, I know the very act of writing to be a political one, and believe that we’re only going to discover that fact more and more under this administration. As for “June,” people fall in love with people all the time — and that is one important truth that this book explores. But/and my books tend to be marketed to a less literary (read: strictly liberal), more mainstream crowd (read: including Trump voters), which means, I suppose, that a girl falling in love with another girl might seem politically radical to some of my readers. I’m thrilled to challenge these readers. I believe that empathy changes minds, and that stories are a great way to offer up empathy on a platter.

I just had a baby girl, which has made this recent election feel very personal. That delightful baby, and my terrified grief about the world she’s inheriting — and the ensuing call to action — has pulled me away from my writing in recent days. But I’m getting a lot of thinking done — and that’s a huge part of my process; I often marinate on a book for years before I write a word. I’ve been fiddling with two ideas since long before this terrible election, and both have activists (in one form or another) as protagonists, and, now that I’m thinking about it, deal with America’s horrible legacy of racism and racist violence. I suppose my work may look more overtly political from the outside as I go forward, although in many ways it will be a return home for me, since my first novel (about two little girls photographed nude by a friend of their family) had the culture wars at its very heart. In writing that book 15 years ago, I learned for the first time that it’s important to craft a decent novel and not just spout propaganda. The risk of propaganda is that it shoots itself in the foot by falling flat.

What about you? What are you working on next, and how has it been affected by the current political climate, and by what you’ve been reading and thinking about lately? When we first met, you were feeling such trepidation and excitement for your first adult novel to come out (although you had already had such success as a prolific YA novelist), and I’m wondering how you are feeling careerwise, and what is calling you.

Wasserman: “Girls on Fire” was an explicitly political novel from the start, but — much like everything else about the book — its themes and arguments transformed over the course of writing. When I began, the Satanic Panic element was much more in the foreground, and I thought I was writing a novel about moral panics and the consequences and victims of repressive conservative mores. That’s all still in there (though if you’d like more of it I highly recommend Richard Beck’s remarkable “We Believe the Children,” with the HBO documentary “Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills” as a chaser). But through draft after draft, my focus shifted to the way female adolescence is shaped, dismissed, fetishized, marginalized and, every so often, empowered by our culture. As you mentioned, I spent a decade writing young-adult fiction — add that to the decade I spent as a pre-teen/teen/college student, and you could fairly say I’ve spent more than half my life working through the questions of adolescence. It turns out I had a lot to say, much of it angry but — I’d like to think — just as much of it joyous, a reminder to anyone who’s forgotten their own teen years that the pleasures were as intense as the pain.

I’m angry more than ever this year, angry every time I read the news or (pretty much) venture into the world. I’m angry and sad and fearful on behalf of so many people who are more immediately vulnerable than I am; I’m angry and sad and fearful on behalf of the world (and, very concretely, the earth). And I find I’m angry and sad and fearful as a woman — which, despite my dog-eared feminism card, is for me a new way of thinking. A new way of being angry.

Beverly-Whittemore: This is such an apt description about what it feels like to be a woman in this country right now.

Wasserman: This election has clarified a lot of things for me, but maybe more than anything it’s clarified how much I believe in what’s being called, dismissively, identity politics. That the world looks different through different eyes. That it matters who’s telling the story.

I’m just getting started on my next novel, and while I’m angrier than I was when I started “Girls on Fire” — and certainly more distracted by Twitter — I don’t think I’m a different writer. What I am, hopefully, is a more self-aware one.

Here’s what I believe: Art is political whether you want it to be or not. Even the choice not to be political — or rather, choosing to believe that’s possible — is a political choice.

And if I had to predict a course for literature to take over the next several years, I’d guess it’s about to become substantially more aware of its own politics. I suspect more and more writers will be asking themselves the questions that we’re asking, will struggle with how to pour their anger and sorrow and frustration into their work, will endorse what they believe is right and critique what they think is wrong, will discover that this is what they’ve always done.

I teach in a low-residency MFA program, where I’m often encouraging students to think through the distinction, as you put it, between propaganda and a good novel. I suspect going forward I’ll be more mindful of pushing equally hard in the other direction — encouraging students to think through the distinction between writing that is simply well written and writing that has something essential to say.

This is the story I tell myself, at least, when I’m feeling hopeless and useless, something else that’s coming up more often lately: That words still matter. That words have power, and it’s not just our responsibility but our privilege to use it.

Beverly-Whittemore: I can’t wait to read what you come up with next, to see your anger burn up the page once again. And to be lucky enough to write by your side.