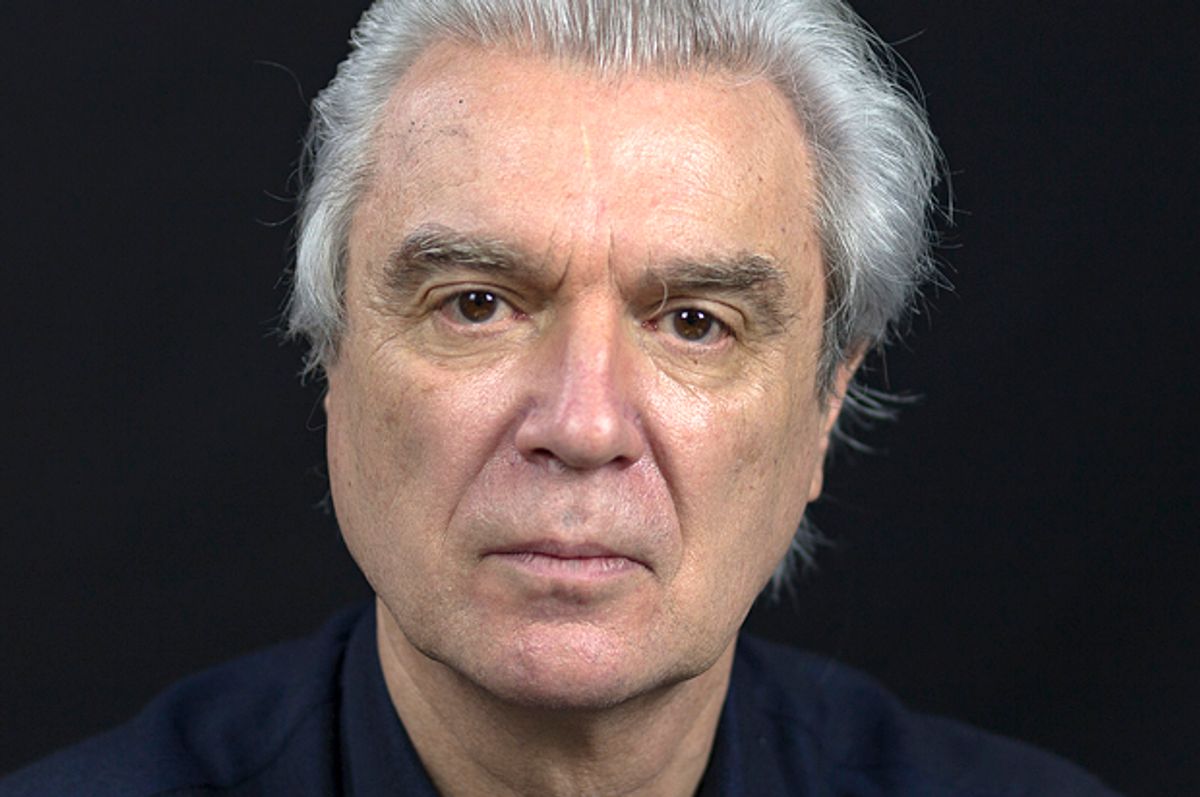

The 1984 documentary “Stop Making Sense” remains one of the greatest concert films of all time. The Talking Heads’ music was certainly infectious, but so, too, was frontman David Byrne’s movements, along with the spectacle of the band working in concert. Byrne’s 2010 documentary “Ride, Rise, Roar” focused on his solo career and mixed performance scenes with interviews and observational footage.

Now Byrne has co-created another concert film, “Contemporary Color,” directed by Bill Ross IV and Turner Ross. The film presents a daylong noncompetitive event at the Barclays Center, featuring 10 high school color guard teams from across North America performing their routines to live, original music by bands and performers like Lucius, St. Vincent, How to Dress Well, Devonté Hynes, Nelly Furtado, Money Mark and AD-Rock (aka Adam Horovitz), Nico Muhly and Ira Glass, among others.

For folks unfamiliar with what a color guard does, it involves rifles, sabers and flags being tossed and twirled in a giant synchronized spectacle. And it’s hypnotic to watch. “Contemporary Color” offers pure joy for 100 minutes as teens perform their routines with a precision that is truly breathtaking. The film is also quite emotional. It is hard to not be moved by the passion in these youthful faces as they perform.

The Ross brothers capture the energy and excitement though onstage and behind-the-scenes footage that they have woven together seamlessly. Byrne, who helped produce “Contemporary Color” and performs one of the songs in the film, met with Salon to talk about color guards, creating the live performance experience and what he played when he was a teen.

There are two guys from Field of View, one of the color guard teams, who talk about how pumped up they get from [being in a] color guard. The energy from the performances is infectious. What drew you to this art form?

I was drawn to this "sport of the arts" as they call it, completely accidentally. Some team — I'm not even sure what team it was — years ago asked to license an instrumental piece of music that I'd done, a pretty obscure piece of music, too. It was done for a theater piece. I thought OK, it was a high school team, they'll get it for nothing. I said, "You'll get it for nothing, but send me a videotape of what you do with it.”

Months go by, and I got not just a videotape of that team, but a DVD of the [color guard] world championships. I sat down and watched it, and as I watched more and more I thought, Whoa! Look at this! Look at what's going on out there that we don't know about! Here's this homegrown, indigenous art form that is incredibly popular all over the country — it fills arenas — parents, children are all deeply immersed and committed to this thing, and we in some of the big cities know nothing about it. And whoever decided what culture is, has kind of overlooked this.

I thought that’s a real shame. This is great stuff going on, really inventive, sometimes a little over the top, sometimes . . . whatever. It deals with issues, it deals with beauty and abstract stuff, and I thought maybe they could have some cool live music.

What were you like when you were a teen? If you weren’t doing color guard, you were performing to some degree? What were you doing?

When I was a teen . . . wow! It sounds like I had it all planned out. [Laughs.] I did art at home, in the basement. I would meticulously draw things, like cartoons, abstract stuff, whatever — and I taught myself to play guitar. When I was in high school, I would sometimes do gigs in the local college coffeehouses.

But you didn't do any kind of group performance in high school or anything like [being in a] color guard. . . . You were much more solo.

No, I was not in [a] color guard. I was much more solo. There was a band for a little time, but that didn’t last very long. I tried to get on sports teams and didn't make the cut.

What sports did you play?

My school had really interesting sports. I went out for soccer, as it's called in the United States. I loved it. I wasn't any good at it, but I loved it. It was the kind of game where all the players get to participate. They are all moving. I thought that's a good game. My school did these pilot programs for other games, that were somewhat related to soccer or basketball. One was called scooter hockey.

You haven't heard of this? Scooter hockey, I have to explain a little bit. It's played on a diamond-shaped . . . almost like a skateboard, but it had wheels on each corner that kind of turned around — casters — and you put your butt on it and you had to move around the gymnasium floor crab-style.

We played crab soccer . . .

This was a variation of crab soccer, which we also had. You had this little stick and it was a hockey puck. You have never seen so many mashed-up knuckles. [Laughs.]

I'm sure that didn't help with your guitar!

When you did crab soccer, did you ever do it with a medicine ball, one of those giant balls?

Yes.

The ball would just completely knock you off your [balance].

Exactly! You would fall over. What did you learn about handling the rifles, sabers and flags? There's a scene in the film where you're trying to twirl the rifle. It looks hard. They do it with such precision!

I'm trying. I'm terrible. Me trying to do it is a bit of a joke. It's much, much harder than people think it is. People think you just twirl the thing and toss it up. And they are kind of impressed. Sometimes the things that impress a naive viewer like myself are not the hardest things to do. The teams know that certain things are really hard to do.

Catching those flags in sync!

Catching the flags in sync is really pretty tough. I'm doing a musical theater project now [“Joan of Arc”], and no surprise, I brought one of the color guard kids in. We have a scene where there's a coronation and we needed some flag stuff. [I asked,] Can you teach it to some of the [cast]? These guys know how to dance. They are actors, but it is hard.

You have been showcased in performance films from “Stop Making Sense” to “Ride, Rise, Roar.” What can you say about the approach to “Contemporary Color”? It is a mix of interviews and observational footage, performance and concert? How much input did you have in coordinating what the film would look like?

The directors are the Ross brothers, who have done other documentaries. Their modus most of the time is to immerse themselves in a community. By immersing themselves, they find out things that are going on. And if they follow that, sometimes a narrative emerges. And they did a little bit of that here. These guys are going to be good at immersing themselves in what is a tight-knit community — color guard people in different towns and across the nation, where they are all kind of networked together.

They hung it all around this event that we did, where we had 10 contemporary musical artists did live music — original songs — with 10 routines that the teams did in an arena. We pulled it off. That was kind of the centerpiece of what they were documenting, but they keep pulling away and you get backstage, you get the backstory of what the teams are doing, the parents talking about. . . . The parents get very involved in this.

Now, your performance was “I Was Changed” in the film. I’m curious what prompted you to select that song? You emphasize when you introduce it, “America has changed.” I want to talk about how music can create meaning. Your Talking Heads song “Crosseyed and Painless” has taken on a different meaning in the Trump era. “Facts are simple.”

I picked this song, rewrote it a bit; I had it partly written. As we were going through this process — we took a couple of years — I became a little bit familiar with the color guard world, and I realized that as you said, it's very emotional. These kids are completely emotionally attached to this. They cry in the middle of their routines. I thought, OK, I can't just do a frivolous song. It's gotta have some big feelings here.

You get that when the young woman runs across the stage and embraces the guy at the end of the performance. That's so moving. What can you say about the pairing of the music to the performers? The songs are all very melodic, and yet they are not dance numbers. They have a very ethereal quality to match the style of the performance. Can you talk about pairing the different types of musicians and the music?

Yeah, a little bit. [In introducing] my song "I Was Changed," I say, "Ladies and gentleman, America has changed" because the day before the show, the gay rights thing went through. A lot of the kids in color guard are discovering who they are sexually, and this is just completely liberating. So LeeAnn [Rossi] in my office and I sat and kind of paired off some of the teams with some of the musical acts thinking this person might be good with this one. You never know. Sometimes we had an inkling of an idea of what a team was going to do, and we thought, Well, that’s going to work. There was one team that was doing a lunatic asylum theme, and we thought, Annie Clark [St. Vincent] is going to love this.

Color guard is a very team-oriented sport. What can you say about solo work versus teamwork? Because I think there that element is going on here. They are all working in sync as a group but they are all also very much individualized — as are the musicians.

Wow. At one point when we were organizing this thing, I thought, Oh, this is going to be crazy; these are high school kids. They are going to be wandering off; it's going to be hard to keep track of them. They are going to be doing gossip-worthy things here and there or wherever. No, they are so focused on what they are doing. They are so dedicated. They are really all in it together to make the team work. Part of that is because they are competitive. Not in the show we did, but in their regular life. They have regional and national competitions.

These are the 10 best teams?

Well, we didn't pick what might be called “the best.” We picked to get a diverse range. Some of them focus on abstract designs. Some of them do issue-oriented routines. So we've got to mix that up. They are so dedicated. They give themselves to the shows, as you see in the documentary. They practice at home. Their lives are [organized] around this thing.

It's great. It shows their commitment and discipline, and it's very inspiring. You watch them and you just feel for them. It’s that emotional connection. You have reinvented yourself from Talking Heads to Brazilian tropical [music] to opera and other genres, theater. What can you say about your musical growth and development, your career arc?

[Laughs.] I think a little bit by design and a little bit, probably a lot, by luck, I've managed to gradually position myself so I had lots of possibilities of things I could do — that I could propose this idea of an event that brings together these high school teams with different artists. In this case, I'm participating in it but I'm kind of more the impresario, even though I don't go onstage, and go, “And now!”

There's another guy [Mike Hartsock] who does that, and he has the voice. He does sports stuff.

It means that I can go to institutions and say, “I have this idea.”

And they don’t look at me like I'm crazy and go, “Well who are you to come up with this? You're a singer-songwriter.” They go, “OK, we’ll look into it.”

There's a risk in making a film like this or doing a live performance like this. Can you talk about that? I kept waiting for a flag to drop, or something to [happen] to upset the magic of what I was watching. It’s such an impressive spectacle, and it’s all done live!

It’s a lot of planning. The Ross brothers are used to working really kind of small, with a small crew. And for this, they had to cover a big show, as well as go down with a small crew to blend in and hang out with the kids and their families. But to cover the show, they had to quadruple the size of their crew and have cameras everywhere to cover all the stuff and hope that they got it, and that it looked good, not miss some of the key moments. They got it. It’s hugely risky. We put all the pieces together and then it was, Is this going to work — work, as in are people going to enjoy this? Or are they going to be scratching their heads going, “What the hell is this?”

I saw this at the Tribeca Film Festival last year. When I read the description, I thought, I have to see this! I had a colleague who worked in [a] color guard. I never attended, but I knew she did it. It’s such a spectacle. What can you say about the spectacle? Who impressed [you] and what was it about them that was impressive?

The teams are kind of amazing. There are some that are a little bit easier to describe what they are doing. When people hear “color guard,” it’s a little bit of a misnomer, what they refer to it as is “winter guard” because it’s performed outside of the football season and they are doing themed routines. So it’s not stuff with the marching bands, but it’s stuff they do with prerecorded music in their own world. And some of the stuff, I can describe to people and say, “Well, there’s one team that does an Alfred Hitchcock theme, and they do these things with flags and sabers, and tossing sabers. They re-enact the shower scene from ‘Psycho’ and the jungle gym from ‘The Birds’ and a bunch of other stuff. And yes, that’s what they do and it’s really good.” And it’s like, What am I seeing?

Shares