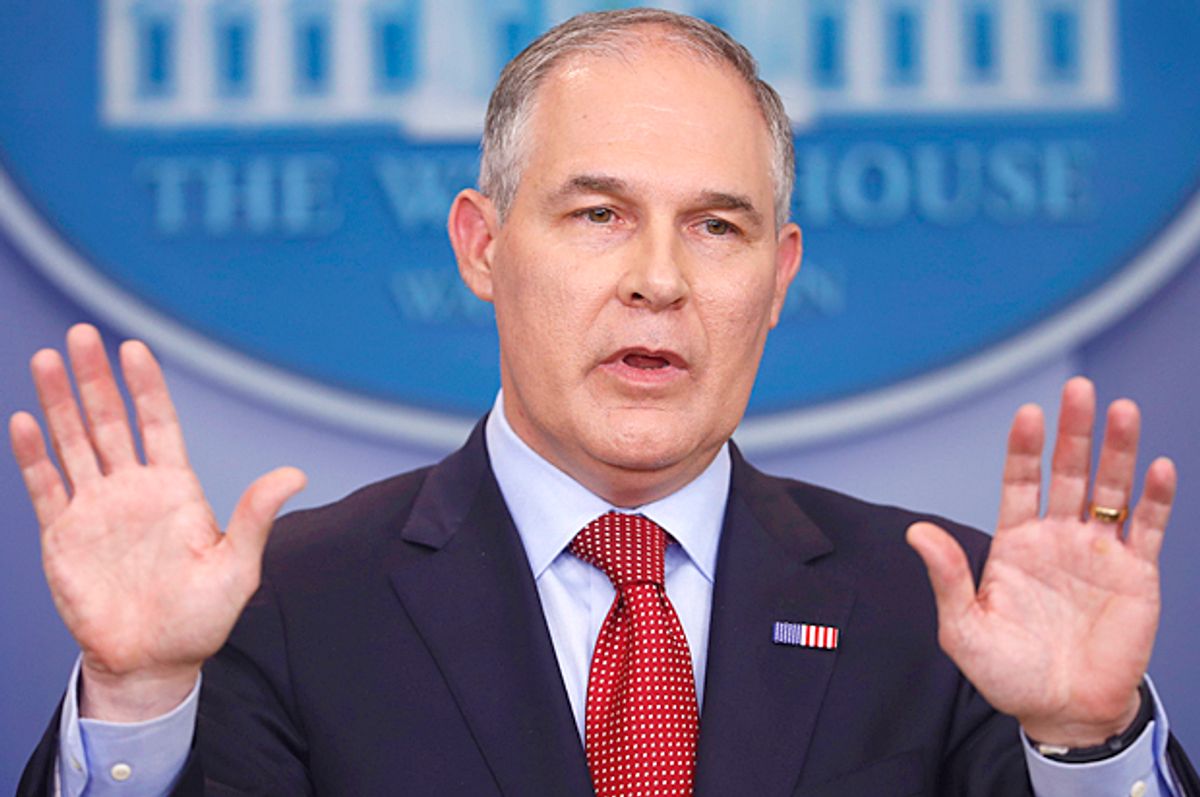

While Donald Trump and his close advisers have managed to best even the most extravagant predictions on their levels of incompetence, the grim fact of the matter is that some of Trump's picks to head various agencies do know what they're doing — and, generally speaking, they are going to leverage that competence for dire purposes. Scott Pruitt, Trump's head of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), is among the top contenders when it comes to using the power of the federal bureaucracy to undermine what his own agency is meant to do.

In his previous gig as Oklahoma's attorney general, Pruitt spent years suing Barack Obama's EPA in hopes of keeping the agency from doing its job. Now that he's on the inside, Pruitt has considerable power to slow down or halt the agency's core mission to reduce the level of pollution in our air and water.

But there's a way that environmental activists or state and local elected officials can fight back and force Pruitt to do the work the EPA head is supposed to do: Sue him. Federal law clearly says the EPA is supposed to protect the environment; if Pruitt doesn't want to do that, the courts have both a right and an obligation to force him to.

This week, the strategy of suing Pruitt into doing his job met with a significant victory. The U.S. Court of Appeals in the D.C. circuit has ruled that Pruitt cannot delay the implementation of a rule written during the Obama years that requires energy companies to limit methane emissions from equipment leaks.

This decision is important in itself, but it's much more significant for its larger implication, which is that the courts can put serious limits on Pruitt's efforts to undermine the EPA's mission from the inside.

“When the executive oversteps his bounds, it’s the job of the court to step in, and that’s what they’re doing," explained Joanne Spalding, the chief climate counsel for the Sierra Club. Pruitt, she said, "cannot ignore the requirements of administrative law, the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act and the other statutes that EPA was formed to implement."

Spalding added, "This methane decision in particular is an indication that the courts are not going to sit idly by while Scott Pruitt tries to dismantle our environmental safeguards."

Despite his history of climate-change denialism, Pruitt has repeatedly insisted he is not opposed to the EPA's larger mission of protecting the air and water from pollution. During his confirmation hearing, he instead argued that he wished "to return the agency to that core mission of protecting the American people through common sense and lawful regulations."

This "return" language is loaded, because its unsubtle implication is that the Obama-era emphasis on battling climate change was a drift away from the agency's original purpose, to clean up and prevent forms of pollution that have negative health effects on Americans. Once in office, however, Pruitt has demonstrated he's just as indifferent to stopping smog as to slowing climate change. For instance, he tried to delay ozone regulations that were focused on unhealthy smog rather than greenhouse gases. States and environmental groups sued the EPA, and likely realizing he couldn't win in court, Pruitt backed off.

There's also a sound legal argument that this supposed distinction between different kinds of hazardous emissions is a false one. In 2007, the Supreme Court ruled in Massachusetts v. EPA that since global warming is a threat to human health and safety, the EPA is obligated to regulate greenhouse gas emissions just as they are required to regulate pollutants that cause smog.

“This was the Bush EPA trying to evade its responsibility to regulate and reduce greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide and methane and others," Spalding explained.

Because of that decision and the years of research conducted at EPA during the Obama years, Spalding added, Pruitt "is obligated to implement that finding. His personal beliefs are irrelevant."

The twin limits that Massachusetts v. EPA puts on Pruitt are, first, that he cannot deny that greenhouse gases are under his purview, and second, that he cannot refuse to do the job the agency is set up to do. As his actions have made clear, however, Pruitt is willing to try all sorts of strategies to delay or dismantle rules that have been put in place by previous administrations, especially the Obama administration.

While the D.C. Circuit Court has smacked down Pruitt's effort to declare a delay in the methane rule, he has another trick up his sleeve. Pruitt has also pushed for a more formal process that would rewrite the original regulations, delaying their implementation by two years so that he can (in theory) review whether or not the regulation, as originally written, is even needed.

Pruitt's EPA is arguing that this proposed rule change is no big deal because it's only a two-year delay — though who knows what his "review" process might produce in two years. But even on its surface, such a delay is a terrible idea: This methane rule is meant to target emissions that are known to cause illness and exacerbate asthma in small children.

“Two years in the life of a toddler is a significant amount of time," Spalding observed.

Must of the resistance efforts to the Trump administration have understandably been focused on legislators, especially on asking citizens to call their members of Congress or confront them at public events. But the president's power is felt at least as much, and likely more, through the management of federal agencies -- and those agencies are also obliged to deal with the public. That's especially true when proposed rule changes, such as Pruitt's request for a delay on the methane regulations, are open for public comment.

"That process is a way for people to engage and make their voices heard, and make it clear that what Pruitt is doing is not only contrary to the law, but also very unpopular," Spalding said. "If the hearing is anywhere near where they live, it’s really great for them to go to the hearings."

She noted, too, that these public comments are often reviewed by courts when determining if a rules change is illegal.

Make no mistake: Pruitt is powerful and will do a lot of damage as head of the EPA. If nothing else, he can be expected to make no positive progress when it comes to fighting pollution and climate change, and will likely get away with undoing some of what was done under Obama. But the situation isn't hopeless. Environmental lawyers and ordinary citizens can fight back, both in the courts and through the bureaucracy's official channels. If Pruitt's toxic anti-environmental agenda can't be stopped completely, it can be stymied.

Shares