Last week I suggested here that President Donald Trump could be viewed as a major protagonist in an internal conflict that is dividing the Western world against itself, a conflict French theorist Jean Baudrillard identified 15 years ago as World War IV. It’s the kind of provocative notion that raises more questions than it can answer: Who is fighting whom, and over what? And did we somehow sleep through World War III? It also risks falling afoul of what might be called the Fukuyama Principle, which holds that anyone who makes confident pronouncements about history while it’s happening around them is likely to be wrong.

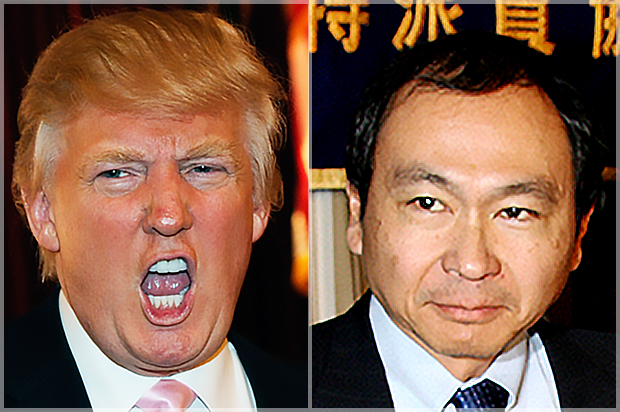

That’s in honor of neoconservative political scientist Francis Fukuyama, of course, who argued in 1989 that the fall of the Berlin Wall and the worldwide triumph of liberal democracy and market capitalism marked “the end of history as such” and the final stage of “mankind’s ideological evolution.” From there on out, it was gonna be washing machines for everybody, nice people in suits running the banks and the bureaucracies, and no more war.

Fukuyama has been widely mocked over the ensuing decades in any number of articles about “the end of the end of history.” Even at the time some critics observed that this was a fatuous, upside-down version of the most utopian form of Marxism, which imagined a classless, conflict-free communist society in some distant human future. To be fair, Fukuyama later admitted that his reports of history’s demise were exaggerated, especially after the events of September 2001. He even renounced the neoconservative movement after the Iraq war turned into an unmitigated disaster — although he had initially been among its biggest intellectual cheerleaders — and morphed into something like a middle-road Obama-Clinton Democrat. Today we might call him a neoliberal, meaning that not as leftist hate speech but an accurate descriptor.

Indeed, Fukuyama is now among the many prominent scholars who are troubled and confused by the current condition of “liberal democracy,” which brings us back to the hazardous project of trying to understand our extraordinary historical moment. Is the rise of Trump, and the worldwide decay of democracy he so dramatically embodies, just a detour or a temporary setback in the upward trajectory of “mankind’s ideological evolution,” or something closer to a historical turning point?

In the spirit of the Fukuyama Principle, it’s only fair to observe that no one can possibly know the answer, and that we all come at such a question with built-in ideological biases. What could be described as the mainstream liberal hypothesis — more or less, that Trump is an unexpected and dreadful phenomenon, but one that can rapidly be corrected through the regular operations of democracy — cannot be dismissed out of hand.

You’ve heard multiple variations of that argument, I imagine: All we need is a razor-thin Democratic House majority in 2019, or our own version of newly elected French President Emmanuel Macron, and all will be well! I’ve made my views known on the likelihood and usefulness of a “blue wave” in the 2018 midterm elections. As for Macron, despite all the media swooning he’s basically a sexier version of Michael Bloomberg, a neoliberal Potemkin candidate who represents the middle of the middle of the European establishment and won a low-turnout election against an outright fascist, in which more than 4 million voters (11.5 percent of the total) either spoiled their ballots or left them blank — a startling protest with no clear precedent in any major Western democracy.

This powerful desire to believe that the Trump phenomenon either didn’t really happen (thanks, Putin!) or doesn’t really matter also requires overlooking the global context. As Fukuyama’s Stanford colleague Larry Diamond, a founding editor of the Journal of Democracy, told NPR’s Ari Shapiro just this week, numerous nations in different parts of the world that claim to be democracies — Turkey, Venezuela, the Philippines, Poland, Hungary and Bangladesh, for starters — have slid toward authoritarian rule over the last few years:

Liberal democracies, I’d say, including ours, are under pressure of becoming less liberal, less tolerant. Countries that are democracies but maybe not liberal ones, like the Philippines, are at very serious risk of sliding back into authoritarian rule. And countries that have been authoritarian are becoming more authoritarian.

Furthermore, the “we got this” argument, in the American context — so redolent of the Hillary Clinton campaign’s 2016 overconfidence — rests on the premise that our democracy was working reasonably well before this bizarre interruption, or perhaps on the more Bernie-fied premise that this crisis will spark a set of urgent reforms that can re-energize and renew democracy. Way too much wishful thinking is involved there, in my view: That feels like nostalgia for the Barack Obama campaign of 2008, when both America and the Democratic Party seemed (albeit momentarily) on the cusp of a hopey-changey new era.

For whatever it’s worth, Mr. “End of History” seems to agree. In an interview with NPR’s Steve Inskeep in April, Fukuyama observed that Trump’s election resulted from a number of long-term trends, including the fact that real wages had stagnated for middle-class and working-class Americans over the last 30 or 40 years. “I actually think it’s quite legitimate for them to blame the elites who promised that, you know, as a result of globalization, everybody would be better off,” he said. Then Fukuyama moved on to the institutions of democracy.

The other thing, I think, has to do with our political system. Quite honestly, you know, well before Donald Trump began saying this, it wasn’t working well. You know, Congress couldn’t pass budgets, it couldn’t — you know, it was very deadlocked. Plus … I think there’s a general feeling that interest groups, people with a lot of wealth and power, have a disproportionate say in the way that our democracy works. And so all of these put together, the institutional shortcomings and the socio-economic impacts of globalization, I think, prepared the ground for a rise of a populist.

And I’m actually surprised it took this long to get to this point because ever since the financial crisis in 2008, I think we’ve been ripe for something like this.

If most of that falls under the heading of Mild Wisdom from Captain Obvious, it also tends to support the World War IV hypothesis, although I doubt Fukuyama would embrace that terminology. In his 2002 essay “The Spirit of Terrorism,” Baudrillard characterized this half-visible worldwide conflict as “triumphant globalization battling against itself.” (Emphasis in original.) It’s worth noting that Fukuyama still uses that anathematized word in 2017, when even people who self-evidently favor the capitalist model of globalization (such as the leadership of both political parties in the United States) have long since stopped saying so.

Indeed, from this distance it seems clear that “The Spirit of Terrorism” was profoundly shaped by Fukuyama’s 1989 “The End of History,” and to some extent may have been intended as a riposte or rebuttal. While these two essays reflect divergent political and philosophical viewpoints and make directly opposed arguments — globalization will last forever vs. globalization is destroying itself — they share the same conceptual framework and are rooted in similar assumptions about the world.

Essentially, Fukuyama and Baudrillard agree about the overall course of 20th-century history, and agree that it culminated in the apparent triumph of liberal democracy and market capitalism, together known as globalization. But while Fukuyama sees that triumph as the final destination of the entire Enlightenment tradition, or perhaps all of Western civilization, the latter argues that all along those things have contained the seeds of their own destruction, and that as the West grew ever more powerful, those internal currents of self-destruction grew more powerful as well.

Baudrillard’s account of history goes like this (and I don’t think Fukuyama’s would differ in any material way): In the First World War, bourgeois democracy destroyed old-school imperialism; in the Second, democracy and communism forged an uneasy coalition to destroy fascism. In the Cold War, which Baudrillard designates as World War III, capitalism destroyed communism, leaving it in full possession of the globe with no visible enemies left to fight. Beneath the arrogance and triumphalism, what could be called a cultural and spiritual crisis emerged almost immediately. As Fukuyama ruefully recognized years later, his blithe pronouncement that nothing could ever again challenge the primacy of consumer capitalism and parliamentary democracy displayed absolutely no awareness of that.

In 1992, the same year Fukuyama’s essay appeared in book form (under the even more dystopian title “The End of History and the Last Man”), Leonard Cohen put it this way:

Give me back my broken night

my mirrored room, my secret life

it’s lonely here

there’s no one left to torture. …Give me back the Berlin Wall

give me Stalin and St. Paul

I’ve seen the future, brother:

It is murder.

Cohen’s mordant prophecy seems to anticipate Baudrillard’s argument a decade later that the 9/11 attacks represented the fulfillment of an inadmissible collective fantasy, and that in their wake the liberal-democratic global order would be transformed into its evil twin, “a police-state globalization … a terror based on ‘law-and-order’ measures.” He saw the future, brother.

I wrote last week that Trump and Osama bin Laden both fit into Baudrillard’s notional World War IV because they represent complementary reactions against globalization and marked “the emergence of a radical antagonism” within a dominant order that previously seemed secure. Baudrillard’s contention that Islamic terrorism was a product of Western society and could not in any meaningful way be regarded as coming from “outside” was controversial in 2002, but seems almost beyond dispute today.

Resurgent white nationalism in the West and Islamic extremism in the Arab world are not the same thing, needless to say. But they are linked and parallel phenomena that share a common enemy and a common goal: They want to undermine or destabilize the entire project of liberal democracy, which they see as a crumbling, contemptible failure. That is the true battleground of World War IV, and it comes attached to a massive philosophical problem: No reasonable person can look at the current state of the world without admitting, like Francis Fukuyama, that the critics of democracy have a point.

One intriguing absence in Baudrillard’s 2002 essay on terrorism is that he never directly discusses democracy or capitalism, the twin pillars of Fukuyama’s Orwellian end-stage of history. I believe the word “capitalism” does not appear at all, perhaps because Baudrillard was a reformed Marxist who wanted to avoid what seemed like an outmoded buzzword. I suspect he believed that Fukuyama was essentially correct, in that every 20th-century ideology that had tried to impede the global flow of capital and the political system that best enabled it — whether that resistance took the form of fascism, socialism, communism or some variety of nationalism or tribalism — had been conclusively defeated.

We now know that history was not over, and that those ideological ghosts of the pre-globalized past did not stay buried. (We have yet to see a resurgence of communism as such, which has a serious branding problem. Nothing’s off the table!) Capitalism has created enormous wealth, and distributed it in grotesquely unequal fashion. In virtually every nation that claims to be a representative democracy, participation has declined and dissatisfaction has risen. America’s paralytic political system is exceptional only because of the naked cynicism of our current governing party, and because of our mythic and laughable sense of self-importance. As I’ve said many times, Donald Trump is a particularly nasty symptom of infection, but he’s not the virus.

This internal conflict and its central question — why our democracy and our economy function so poorly, and whether they can be repaired — contaminate every aspect of political, economic, social and cultural life, often in ways that are not obvious. They are definitely the source of much of the tension and bitterness on the broad-spectrum American left, which so often seems out of scale to the actual issues in dispute.

When mainstream liberals perceive the Bernie-flavored radical left as in some sense allied with Trump and Putin — that is, as enemies of democracy, at least as it currently exists — they’re not entirely wrong. But wait: When the radical left perceives Hillary-style Democrats as a totally inadequate resistance to Trump — as defenders of a compromised and corrupt system that has given up on addressing the most fundamental social questions — it’s not entirely wrong either.

What Donald Trump represents in World War IV is not much of a mystery. As I wrote after his shocking speech in Warsaw a few weeks ago, he may be “the symbolic end point of Western civilization,” or at least the ironic “fulfillment of its most diminished and malicious tendencies.” But who is fighting against Trump and Trumpism most effectively, and what kind of victory is even possible in this ambiguous, undeclared war — that’s not clear at all. Those are questions we will have to return to in another installment.