In the Algiers of the ’30s, a nameless, scrawny gray cat belonging to a cheerful old rabbi, Abraham Sfar, eats the rabbi’s parrot and discovers that he can talk. The cat loves the rabbi’s daughter, Zlabya, and the rabbi is uncomfortable with the talking cat hanging around her: he’d better study the Torah and the Talmud, lest he give her bad ideas.

That’s the premise that begins the French cartoonist Joann Sfar’s graphic novel series “Le chat du rabbin.” (The first three volumes were collected in English in 2005 as “The Rabbi’s Cat”; the fourth and fifth have just appeared as “The Rabbi’s Cat 2.”) The joy of the series, though, is that it hasn’t quite stuck with that setup. Instead, it has become a loose, playful exploration of a lost moment in Jewish culture, riffing on the Sfar family’s history and drifting freely between precise historical details, enthusiastic tall tales and meditations on what it means to live as a person of faith in a world that doesn’t share it.

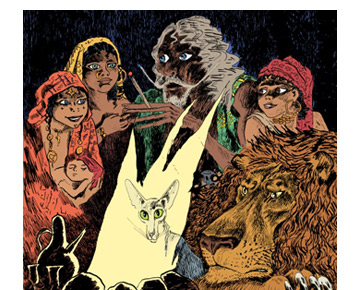

A madly prolific cartoonist, Sfar has published over a hundred books in France. (A handful of them have been translated into English; “Klezmer” is also worth a look, as are the many volumes of “Dungeon,” his collaboration with Lewis Trondheim and a handful of other veterans of the French avant-garde comics scene.) Unsurprisingly, he’s also a very fast cartoonist, and the look of “The Rabbi’s Cat” is splendidly casual. Even his panel borders wobble as if he’s drawing them with his less dominant hand, and some images are just a few thick and thin slashes of ink, as if he can’t get the lines down quickly enough to keep up with his story. In places, his drawing style is a bit like New Yorker cover artist Edward Sorel’s fluid chicken scratch, but Sfar’s work has enormous stylistic variation even within individual panels: The rabbi, whose face is two dots for eyes, a big semicircle for a nose and three smaller arcs for eyebrows and a mouth, sometimes appears next to his cousin Malka, an aging lion tamer and huckster who’s meticulously caricatured and shaded.

The first section of “The Rabbi’s Cat 2,” “Heaven on Earth,” focuses on the cat’s observations of Malka, as well as his lion and a snake that follows them everywhere and considers himself an angel of mercy. (“One night I’ll hide in their shoes,” the snake declares about Malka and his lover. “And I’ll bite them almost at the same time. That will be my gift. That way, they’ll die together.”) One keenly constructed sequence drifts gradually from the cat’s 6-inches-above-the-ground narration into a grand, fabulist tone, until the story erupts into violence and the death of Malka and the lion — and then cuts away to Malka, explaining to a thrilled crowd of children that “that’s the story of one of the many times that I died.” Sfar never bothers to indicate where the main narrative has become the tale-within-a-tale, but that’s deliberate. Malka is trying to become a legend by conflating the particulars of his life with the glorious death he won’t have: “He wants future generations to come looking for his grave as a place of pilgrimage, seeking his protection.”

The legend, he knows, will soon be all that’s left of him and his lion; we know that it will also be all that’s left of his community. The ’30s weren’t a particularly propitious time to be Jewish, and there’s a constant undercurrent in these stories of the encroachment of hatred around Jews wherever they travel in Europe and Africa. Near the end of “Heaven on Earth,” the rabbi’s students are thinking about learning how to fight the anti-Semites they’ve been warned are looming; he tells them that they’d be wiser to spend their time studying, because “the day they come to kill you, you’ll die anyway,” but that way at least they’ll have read some books first.

The other, longer story in the new volume is “Africa’s Jerusalem,” a zigzagging tale that starts out as a “Tintin”-like adventure and eventually evolves into a love story, graced at its conclusion with bracing flashes of eroticism. (Tintin, in fact, comes in for a drubbing: He turns up for a page as an arrogant, racist reporter, Sfar’s upraised middle finger to French comics master Hergé’s infamous “Tintin in the Congo.”) In an introductory note, Sfar claims that “Africa’s Jerusalem” is “a graphic novel against racism,” which it is, but it’s also another opportunity for him to avoid the risk of the series falling into a formula.

The story begins when the rabbi receives a mysterious crate; instead of the books he expects, it contains a Russian Jewish painter who has tried to ship himself to Addis Ababa to find a rumored Jewish homeland in Ethiopia. (He only speaks Russian, and the Algerians don’t understand it at all; fortunately, the cat understands all languages.) Joined by a rich, arrogant local Russian man and the rabbi’s cousin, a sheik who’s also part of the Sfar family, they drive off to find Jerusalem in Africa.

What they discover along the way are a lot of questions about the relationship among art, faith and truth. When the Russian artist starts painting a portrait of Zlabya, her husband furiously (and jealously) insists that it’s forbidden by the Second Commandment’s prohibition of graven images. The painter (via his translator) insists that if golems are permissible for rabbis to make, his art isn’t idolatry but prayer: “He say God do very good job creating beautiful women and he say thank you. His golem is not for copy God, it is for make contemplate how God is a good worker.” The final panel of the book is the Russian artist, lying naked beside his new wife (an also-unnamed African woman he has met in a bar en route to Ethiopia), declaring that “telling things like they are is not my job.”

Is it Joann Sfar’s job, then? Not if he can help it: His Algiers is a city built on family anecdotes and historical research, but it’s mostly the amorphous, edge-frayed invention of a tale spinner. Whether by design or accident, “The Rabbi’s Cat” stories perpetually swerve around in tone and style, as if Sfar’s improvising them a panel at a time. Characters wander out of the story, then back in again; the mood is rarely laugh-out-loud funny, but lingeringly amusing, except when it turns shockingly sad or peaceful and reflective for a page or two; any scene could be a theological discussion, a broad bit of slapstick, a digression on animal joys, a set of nature drawings.

What keeps the book’s free-form ramble from dragging it off-course is the joy Sfar takes in his characters’ voices and the whirling brio of his drawings. Even his most outrageously abstract scribbles feel observed: His cat is a doodle whose shape is no more catlike than Garfield, but has the lanky body language and capricious presence of a real alley cat, with an ineradicable cruel streak that’s instantly evident from his circle-and-dot eyes. Sfar’s drawing style casually breaks all the rules of proportion, neatness, shading and perspective, the kind of violation that can be committed only by somebody who has studied those rules Talmudically. “Blessed are you, Lord our God, who allow us to transgress,” Rabbi Abraham prays in the first book, as he digs into “the least kosher meal in the universe.” (“And a glass of milk with the ham. And a good wine named after a church or a Virgin Mary.”)

Studying and religious law, naturally, are major concerns for most of Sfar’s human characters here: They’re ways to impose comforting order on a world whose rumble is getting steadily more menacing. Rabbi Abraham quarrels with other rabbis who interpret Jewish law dogmatically, but he’s also so used to understanding his experiences through books that he has to be reminded to pull his nose out of his Citroën travel guide and see the African landscape he’s passing through for himself. And when the cat suggests that perhaps he should just silently observe his unfamiliar surroundings, Abraham says, “You mean make no comments? Have no opinion on what I’m seeing? … I’ve never done that.” The cat, of course, follows no law but his own impulses. As much as Sfar’s work radiates affection and respect toward the ancestors he has imagined, his true sympathies are with the cat’s freedom to lie, to disregard formality and to dart off in any direction his whim takes him.