A gorgeously composed and acted film set in an isolated community of Trappist monks in the mountains of overwhelmingly Muslim Algeria, “Of Gods and Men” is both a moving, almost abstract parable of faith and an all too real episode drawn from recent history. This is a tough movie to sell, especially given that even a cursory Internet search will tell you more than you want to know about the end of the story. It’s set in the mid-’90s, when a wave of fundamentalist Islamic terrorism swept across Algeria, making life there exceedingly difficult for foreigners, especially when they represented both Christianity and the legacy of French imperialism. (To be fair, the vast majority of the people killed by Algerian terrorists in that period were not foreign or Christian — and the film makes that clear.)

At a moment when the world’s attention is intensely focused on the internal divisions of the Arab and Muslim world, “Of Gods and Men” also strikes me as a strikingly important film imbued with the kind of wisdom that can’t be summarized in words. (Go ahead, roll your eyes. It’s true anyway.) As a cinematic study of religious faith and its consequences, it may well rank alongside the work of Robert Bresson (“Diary of a Country Priest”) or Carl Theodor Dreyer (“The Passion of Joan of Arc”). Little by little, French director Xavier Beauvois (who co-wrote the screenplay with Etienne Comar) draws you into the worldview of his characters, who may at first seem like a passel of doddering, deluded and hopelessly naive fanatics. By the time the movie is over, you understand that their decision to stay and face a fate they could clearly see coming was the natural and even inevitable consequence of their convictions.

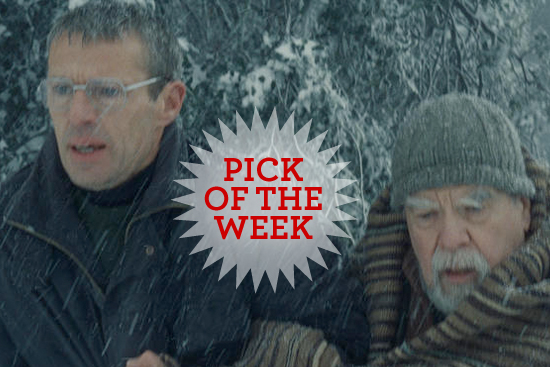

None of which is to say they weren’t kind of nuts. To most European viewers, the general story of the monastery of Tibhirine, and what became of its monks in 1996 as they were pinioned between the rising tide of terrorism and a corrupt Algerian regime, is well known. Beauvois’ film has plenty of dramatic tension, but it is not terribly concerned with suspense in the ordinary sense. In fact, the “what” and “how” of Tibhirine is not his subject — there are definitely unanswered questions about the monks’ fate, and “Of Gods and Men” makes no effort to answer them. What he conveys, through austere but spectacular visual language, magnificent liturgical singing and an ensemble cast headed by the terrific French veteran actors Lambert Wilson and Michael Lonsdale (the latter’s career goes back to the late ’50s), is something of the “why.” In particular, Beauvois is trying to reclaim the terrible story of Tibhirine from right-wing xenophobes who might use it as an excuse for anti-Muslim propaganda when the monks, as the evidence suggests, had something very different in mind.

When the severe but eloquent head of the monastery, Brother Christian (Wilson), comes face to face with a guerrilla leader named Ali Fayattia (Farid Larbi) who has come through the gates with his armed band on Christmas night, the monk meets the invader with a verse from the Quran that mentions Christian priests and monks. The moment seems pregnant with awful possibilities; will the guerrilla be outraged by this unbeliever’s use of the Prophet’s words and massacre them all? Instead, Ali Fayattia finishes speaking the verse himself and soon departs, apologizing for interrupting the birthday celebration of Jesus (an important Muslim prophet). He extends his hand to Christian and the latter takes it, after a moment’s consideration.

That scene embodies many of the themes in “Of Gods and Men” in a single moment. Christian knows that he is shaking the hand of a murderer, and that this truce between the defenseless monks and the Islamist zealots determined to destroy the semi-secular Algerian state is unlikely to last long. In a sense, you could argue, he is sealing his fate with that handshake. The only options available to the monks after that are to flee to France and abandon almost everything they stand for — service, humility, the confraternity of Christianity and Islam, and the example set by the man for whom their religion is named — or to stay behind, care for their beehives and gardens, and stand with the people of Algeria to whom they have already given their lives.

“Of Gods and Men” is now playing in New York and Los Angeles, with wider national release to follow.