Japanese director Koji Wakamatsu’s “United Red Army” is three hours long, mixes drama and documentary in an often-disorienting Brechtian collage, and would be wildly confusing to all but a tiny handful of American viewers (which does not include me, by the way). It’s about as nichey as a niche film can get; I’m impressed that Lorber Films is actually giving it a one-week New York theatrical run on the way to home video. But if you’re keeping tabs on the recent cinematic reconsideration of 1960s and ’70s left-wing terrorism, Wakamatsu’s devastating chronicle of the ultra-violent fringe of Japanese student radicalism is a must-see.

It’s not as if the global wave of radical violence, extending from the Black Panthers and the Weather Underground in the United States to the Irish Republican Army, the Red Brigades in Italy, the Red Army Faction in West Germany and various Palestinian and/or Arab groups in the Middle East, is a brand-new topic for film and literature. (I assume that various Ph.D. candidates have already noticed and explored the fact that the defeated Axis powers — Germany, Japan and Italy — produced the scariest varieties of left-wing wackos.) Headline-grabbing events like the Patty Hearst kidnapping, the murder of Italian premier Aldo Moro or the 1972 Olympic massacre in Munich have been retold several times. But as the global political chaos of that era has faded into collective memory — and if you weren’t there, it’s nearly impossible to convey the level of craziness — filmmakers have given themselves permission to reexamine it from formerly forbidden points of view.

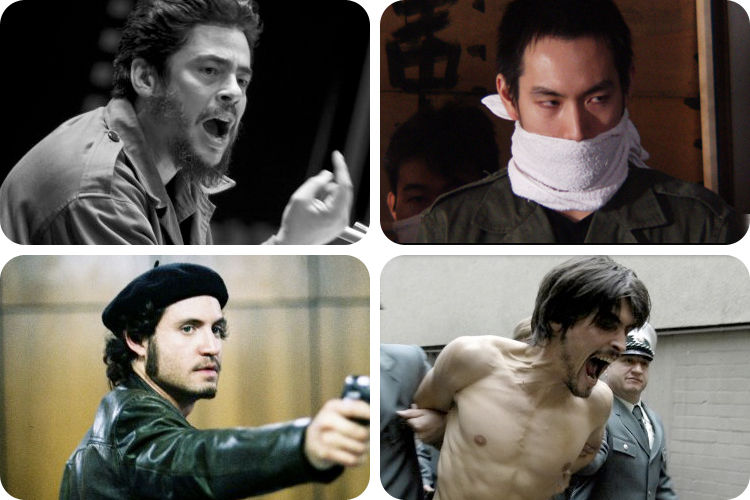

“United Red Army” is at least the fourth major film of the last three years to explore the subjective reality of those who tried to foment global revolution by violent means, on the fringes of a Cold War world that teetered on the brink of nuclear annihilation. First of these was Steven Soderbergh’s messy, mesmerizing “Che” (originally a project designed for Terrence Malick), a great, sprawling, four-hour, two-part naturalistic novel of a movie that captures the iconic ’60s guerrilla as a brave and ruthless man of action, whose arrogance and ambition led to his greatest victory and his ultimate defeat. Some viewers accused Soderbergh of dewy-eyed left-wing nostalgia or ideological whitewashing, but I think those people misunderstand several things: the point of the movie, the ambiguous depths of Benicio del Toro’s performance and the historical character of Che Guevara himself, a figure who continues to resonate throughout Latin American political culture long after his death.

Uli Edel and Bernd Eichinger’s Oscar-nominated “Baader Meinhof Complex” set West Germany’s legendary student radicals against the vivid social context of a repressive American client state still suffering from Nazi hangover, where fervid Trotskyist rhetoric seemed to spread like herpes (and often via the same vectors). I don’t think anybody took “Baader Meinhof Complex” as an advertisement for its protagonists’ increasingly isolated and paranoid worldview. If anything, it may be too easy to view the film as a time-warp, rock ‘n’ roll freak show while missing its larger point: If ultra-radicals like the Baader-Meinhof group drove themselves crazy, the world around them was already plenty crazy, and their amateurish and petty acts of violence were small potatoes compared to the wars and proxy wars and acts of state terror being perpetrated all over the place by the Cold War powers, mostly for entirely cynical reasons.

You could say that the molecular decay of political idealism into cynical opportunism is the grand theme of Olivier Assayas’ miniseries “Carlos,” the undisputed masterpiece of this recent mini-genre. Once again, those who suspect some kind of radical-chic, rose-colored-glasses agenda either haven’t seen the film at all or are so ideologically poisoned they lack all critical judgment. In the amazing performance of Edgar Ramírez, notorious ’70s bomber and hijacker Carlos the Jackal begins as a committed Marxist revolutionary (and dashing ladies’ man) who modeled himself after Che Guevara, and slides over the course of the decade into a slovenly henchman for hire, working for the East German regime, Saddam Hussein, Syrian strongman Hafez al-Assad and even the Iranian mullahs, before ending up as a fat, drunken, pseudo-Muslim exile in the Sudan.

Much of the appeal of this improbable era and its outsize characters is, I think, purely narrative: The world of Carlos and the Baader-Meinhofs, of hostage-takings and 747 hijackings and car-bombings on the streets of Paris and London, feels like a fictional alternate universe but is in fact a reality many of us have striven to forget. The events of these films also feel like a secret spider-web threaded through the underbelly of the Cold War world. They provide history and context to Osama bin Laden and al-Qaida and 9/11, phenomena often presented as having appeared out of nowhere. (You know: They hate us for our freedom, etc.) They remind us that the global victory of technological consumer capitalism, which today seems as natural and inevitable as breathing air instead of water, looked far from a sure thing 40 years ago. It’s way too grandiose to say that these demented leftists from another day have a prophecy to deliver, or anything like that; it’s more as if they’re haunting us, like Hamlet’s ghost, and like the young prince we’re not sure what they’re trying to say.

In most cases these filmmakers are excavating news events they either remember dimly or not at all, but the case of Koji Wakamatsu is quite different. An eccentric Japanese cinema veteran best known as a pioneer of softcore erotica, or “pink” films, Wakamatsu is also a longtime political activist and a former supporter of the radical fringe. In 1971, he co-directed a manifesto called “Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War,” in which a pair of violent sects on the Japanese left officially joined forces with a group headed by Palestinian radical Wadie Haddad (Carlos’ boss and mentor) and declared war against the United States, NATO, Israel, the Japanese government and pretty much anybody else who might be standing in the way of worldwide Marxist revolution.

So it’s hard not to see “United Red Army,” a hybrid docudrama that depicts the group’s harrowing descent into cult-like insanity and self-immolation, as Wakamatsu’s 190-minute mea culpa. It’s as if the 76-year-old filmmaker were asking two interrelated questions: How could the idealistic tide of anti-American activism and socialist internationalism have led to this conclusion, with a handful of isolated zealots beating each other to death in the alleged spirit of Marxist “self-critique”? And how in the world did I fall for it so hard? Those are very big questions, and it’s a bit too easy to view them patronizingly from the 21st century, as if the entire history of the 1960s and ’70s were a collective hallucination en route to the invention of the iPad.

If Che and Carlos and the Baader-Meinhofs and the United Red Army are sending us a message, it isn’t anything as simple as “We were right all along,” because mostly they were wrong and even when they were right they drew the wrong conclusions. It’s more like they’re delivering some kind of opaque biblical wisdom, along the lines of “For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then we shall see face to face.” We should not be too confident that we see the past clearly and understand it, or that our age of permanent electronic distraction and overwork and economic decline, when politics has become an idiotic circus of Newtonian reaction, is possessed of superior wisdom and does not, after its own fashion, contain the seeds of its own destruction.

“United Red Army” plays this week at the IFC Center in New York, with other venues and home-video release to follow. “Che,” “The Baader-Meinhof Complex” and “Carlos” are all available on home video.