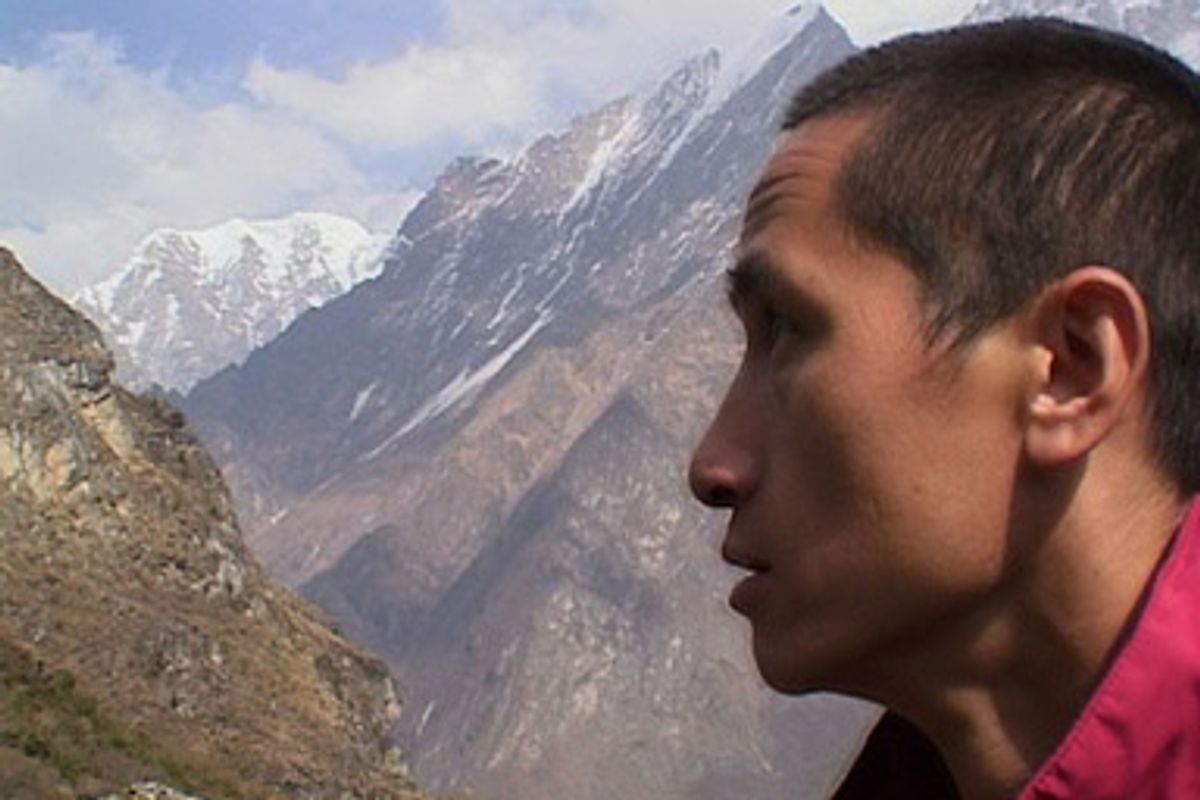

Courtesy of Oscilloscope Laboratories

Tenzin Zopa in "Unmistaken Child."

No aspect of Tibetan Buddhism is as well-known, or seems quite as mythological to outsiders, as the faith's apparently literalistic belief in reincarnation. Taken as a whole, Buddhism is such a diverse and wide-ranging religion that it very nearly lacks any central doctrines or dogmas. Many Buddhists could be called nontheistic or even atheistic, and the widespread Buddhist belief in reincarnation takes many different forms. To some Zen Buddhists, for example, reincarnation is primarily a metaphor or a folkloric remnant.

But within the Tibetan Buddhist world, as we saw in Martin Scorsese's powerful drama about the young Dalai Lama, "Kundun" -- and as we now see in Israeli filmmaker Nati Baratz's remarkable, vérité-style documentary "Unmistaken Child" -- reincarnation is unmistakably real. That is, belief in reincarnation is unmistakably real. What are we actually seeing in Baratz's film, when we watch a group of middle-aged monks identify a 2-year-old from a Nepalese mountain village as the "unmistaken child," a newly reborn version of Geshe Lama Konchog, a world-famous Tibetan teacher who died in 2001? Like most Western, non-Buddhist viewers, I'm not quite sure, although I definitely incline toward a cultural or psychological explanation.

Over the course of "Unmistaken Child," the reincarnation of Lama Konchog becomes vividly clear to everyone in the story, including the child himself, but most of all to Tenzin Zopa, the impish, emotional, free-spirited monk who is Baratz's central focus. Tenzin Zopa, who looks to be around 30 when the film begins, was Lama Konchog's most intimate disciple from the time he was 7 years old. Left heartbroken by his teacher's death, he is now charged by the Dalai Lama with the responsibility of finding Lama Konchog's reincarnation among the recently born children of Nepal and northern India. (This movie and its subjects do not venture across the border into Chinese-controlled Tibet, or at least if they do they don't tell us about it.)

There have been any number of movies about Tibet and its esoteric Buddhist tradition over the past decade or two, largely connected to worldwide concern over the Chinese government's conduct in Tibet and the worldwide popularity of the Dalai Lama, the country's exiled religious and political leader. "Unmistaken Child" stands above most others in offering us an intimate look at Tibetan Buddhism in action, with no external commentary or narration. Tenzin Zopa, a puckish, lighter-than-air presence who speaks English well, is our only guide through this supernal landscape of rugged mountains and lush valleys, wearing Nikes, a North Face fleece jacket and his saffron monk's robe as he travels from village to village -- sometimes by helicopter -- searching for potential reincarnated lamas in the guise of goop-faced, rotund toddlers.

This approach may lead to more questions than answers, but it's definitely an ingenious way of handling the film's epistemological problems. Practitioners of Tibetan Buddhism will presumably watch the remarkable scene when Tenzin Zopa's selected child correctly identifies the rosary, prayer bell and hand drum used by Lama Konchog and nod: This is the right kid. Others of us may wonder about the not-so-subtle cues the child is offered during the ceremony, or speculate that he has been coached on which objects to choose. One way of interpreting "Unmistaken Child" is as a deeply ingrained exercise in cultural suggestion, one that a bright, imaginative child can quickly understand and elaborate upon. Be that as it may, the kid believes it as much as the adults do. When the little boy points to a picture of himself next to a picture of the late Lama Konchog and says, "That's me. And that's me. Those are both me," it's an amazing moment.

Now, I'm not so sure the kid in "Unmistaken Child" understands that this revelation or role-playing game or whatever it is will determine the course of the rest of his life. "Being" the reincarnated lama gets him and his parents a lot of attention. It also means that he will be taken from them, have his head shaved, and be raised by monks as a kind of protected prodigy in a secluded Nepalese monastery. His life will be devoted to saving all sentient beings from suffering and transmitting the ancient traditions of Tibetan Buddhism in a fast-changing world, and I don't dispute the value of those things. What we see at the end of Baratz's beautiful and enigmatic film, however, is a little boy crying because his mother has left him with strangers.

"Unmistaken Child" is now playing at Film Forum in New York. It opens June 12 in Los Angeles; June 26 in Denver and San Francisco; July 3 in Santa Cruz, Calif., and Washington; July 10 in Phoenix and Portland, Ore.; July 17 in Boston and Seattle; July 24 in Chicago, San Diego, Tucson, Ariz., and Austin, Texas; July 31 in Charlotte, N.C., Minneapolis and Sacramento, Calif.; Aug. 7 in Ann Arbor, Mich., Madison, Wis., and Tallahassee, Fla.; Aug. 14 in Kansas City and Santa Fe, N.M., and Aug. 21 in Philadelphia, with other cities to follow.

Séraphine A luminous, slow-moving period piece with a central core of quiet mystery, French director Martin Provost's film about self-taught "modern primitive" painter Séraphine de Senlis (Yolande Moreau) will provide immense rewards to patient viewers. A multiple award-winner at the Césars, or French Oscars, "Séraphine" is not a picture that yields its secrets easily. In its first half-hour, little is revealed about its title character, a blowsy, middle-aged cleaning woman of few words who strikes up a tentative acquaintance with German art dealer Wilhelm Uhde (Ulrich Tukur), who has his own reasons for hiding out in a provincial French village in 1914. War is on the way to sweep the old European order away, but when Uhde sees the paintings on wood that Séraphine has been making -- inspired by her religious visions, and with paints made from secret ingredients -- he is convinced he has discovered an unknown genius.

Uhde and Séraphine were real people, but Provost is no more concerned with telling a "true story" than Tarkovsky was when he made "Andrei Rublev." The comparison is purposeful; if "Séraphine" isn't quite at Tarkovsky's level of difficulty, it is nonetheless a film whose beauty arrives moment by moment, and it requires you to abandon most narrative expectations. Just when you think you know where the story of Uhde and Séraphine is going, it isn't going there anymore. Provost does a marvelous job of capturing Séraphine's world, in which her remarkable, van Gogh-inflected paintings are not inherently more important than her prayers to the Virgin or her work as a laundress; all are part of the same humble, worshipful existence (or, if you prefer, the same borderline mental illness). Yolande Moreau is an astonishing actress, mime and comedian whose physical type would prevent her from being a movie star elsewhere in the world, and her work is always worth seeing. If you turn off all that electronic crap in your pockets and sit still for it, "Séraphine" will be one of the year's most memorable moviegoing experiences. (Now playing in New York and Los Angeles, and opens June 19 in Chicago, Philadelphia and Washington, with more cities to follow.)

"The Art of Being Straight" You have to hand it to writer, director and actor Jesse Rosen, who has managed to make his debut film, a pleasant but completely familiar post-collegiate, welcome-to-the-big-city indie comedy, into a minor news event. Barely feature length at 67 minutes, "The Art of Being Straight" follows Jon (Rosen), a 23-year-old with a Casanova reputation, to a new life in Los Angeles. He's living with his standard-issue homophobic-dude roommates but working at an ad agency, where he gets hit on by his studly gay Latino boss (Johnny Ray Rodriguez). To his own surprise, Jon goes for it and pretty much digs it. But the next day he does the deed with that slutty chick who was diggin' him at the pool hall, and ... wait! Is he gay but overcompensating? Is he straight but foolin' around? Or is there -- gasp! -- another possibility, somewhere between 100 percent hetero and full-on homo?

I don't mean to be snide. OK, I do, a little: It just seems that every generation has to discover for itself that sexuality hardly ever fits all the way inside our preordained envelopes. (I am so immeasurably much older than Rosen that I came of age during the David Bowie era, when it was socially beneficial to pretend to be bisexual, especially when you weren't.) The frankness and sincerity of "Art of Being Straight" is infectious, and Rosen gets some nice performances, especially from Rachel Castillo as Jon's pot-smoking, lesbian college pal who's feelin' the unexpected hots for the hipster guy next door. But if you're going to make the "bisexual movie," it badly needs some actual sex appeal, which both includes the on-screen bodies and transcends them. This one is just bland and pretty after the fashion of so many L.A.-made indies; it could be a viable industry calling card, but it lacks the erotic undertow and cinematic verve of the mainstream TV series Rosen thinks he's mocking. (Now playing in New York. Opens June 12 in Los Angeles, with other cities and DVD release to follow.)

Shares