Billed as a “companion piece” to John Singleton’s hugely successful debut “Boyz N the Hood,” “Baby Boy” might more aptly be called a mediocre knockoff. The film opens with a shot of the adult Jody (model-rapper Tyrese Gibson) naked and in utero. The image clumsily encapsulates the film’s theme: No one will let black boys grow into men.

Jody is a tall, deep-voiced 20-year-old Californian with two kids, but, see, he’s really just a child. It’s a promising premise, but Singleton wants to make absolutely sure we get it. And after scene after scene after scene of various adults yelling at him to “grow up,” and “leave the nest,” we surely, mind-numbingly do.

The issues here are complicated ones, and Singleton ambitiously tries to avoid trite explanations and solutions. How can Jody ever hope to be a real man — and a real father — when he’s clearly never had any decent role models? He’s browbeaten regularly about his lack of a job, his pathological philandering and his stubborn reluctance to move out of his mama’s house, but the ladies in his life still grudgingly support him. And his cronies are in the same boat — they all talk big about “their” cars and “their” homes, but in reality, they have nothing of their own, nothing that they’ve earned.

Jody atrophies in his own self-satisfaction. So what if he cheats on his loyal girlfriend Yvette (Taraji P. Henson), the mother of his young son? He tells her he lies to her because he loves her, that he’ll probably even marry her someday. He brags to his mother about how he drives Yvette to work and picks her up, as if these humble acts alone were the essence of a committed family dynamic. For a little extra cash he hustles a bit of stolen clothing here and there, despite a prior stint in jail. In his social sphere of lowered expectations, Jody’s a big success. The irony is that in many ways he really is, first and foremost because he’s alive, a survivor of a world of random violence and pointed vengeance.

But when complacence is the heart of his story, it’s difficult to work up any enthusiasm for him either. Jody is supposed to be a complicated, morally ambiguous urban Everyman. Instead he mostly seems emotionally indifferent — a laconic figure with some preferences but few strong opinions. He loves Yvette, but not so much he’s going to stop stepping out. He loves his mother enough to be wary of her gruff, ex-con boyfriend Melvin (Ving Rhames), but not as much as he fears Melvin will talk her into evicting him from Hotel Mom.

Things are never black and white in Singleton’s films, and a nobler Jody would not necessarily be truer or more interesting. What would be more effective, however, would be to spend a little less time on variations on the same confrontational “Be a man already” scenes and a little more time exploring Jody’s psyche. He has troubling dreams of death and loss, but who is he? Is he trying so hard to not be his wife-beating father that he’s paralyzed from being anything at all? Is he so haunted by the violent death of his brother that he can’t bear to leave his mother? Or does he just not know what to do with his life because none of his friends do either?

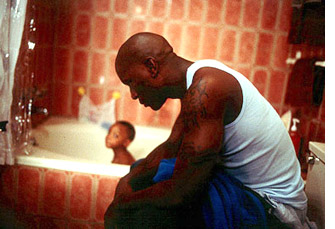

The why of Jody is puzzling enough; it isn’t helped by the awkward performance of newcomer Tyrese. Other actors around him gamely convey their characters’ frustrations and aspirations with depth and soulfulness. Rhames, his biceps so big his arms can’t lay flat against his sides, his voice so forbidding that every word sounds like a growl, reveals the edgy essence of Melvin while keeping you guessing about his motives. And Omar Gooding, as an Augustinian homebody who wants salvation — but not quite yet — is a fascinating bundle of contradictions. Both men, in fact, are the kind of flawed, complex individuals who could have made an intriguing hero of a movie.

Tyrese, in contrast, looks like he’s been busy learning to memorize lines instead of focusing on how to say them. Singleton’s frequently awkward dialogue never sounds less credible than when it’s coming from the actor’s uncomfortable-looking mouth.

A movie that’s just plain bad is a giveaway; you can chalk it up as a loss and forget about it the next day. A movie that, with more mindfulness and care, could have been fresh and provocative and smart sticks in your head even as it exasperates.

Singleton is unquestionably a gifted filmmaker. His directing, especially in simple, quiet scenes of characters doing things as mundane as driving and vacuuming, have a warm, invitingly intimate glow. But in his quest to do it all, he’s lost something along the way. His words are no fitting match for his visuals, and his metaphors are so heavy-handed — a game of solitaire after a breakup, a blossoming garden with a few stray weeds — they undermine the smart subtlety of the direction.

Jody may wrestle with conflicting desires like most of us, but his lessons on growing up and moving on never ring more than halfhearted and false. And for all he endures, Jody never seems to grasp that doing a few things right isn’t the same as doing the right thing. Unfortunately, neither does Singleton.