Here’s a news flash: War is hell. All right, it helps if we don’t forget that, especially at this time of pseudo-war, when the distant, ambiguous conflicts playing out in Whateveristan or Televisionistan seem more like video games, or breathless “reality” specials hosted by Ashleigh Banfield, than the real thing.

In “Black Hawk Down,” adapted from the nonfiction best-seller by journalist Mark Bowden, Ridley Scott is after the real thing: a grueling, relentless, moment-by-moment account of the 1993 battle in which two U.S. Army helicopters were downed and nearly 100 Special Forces troops were trapped overnight in a hostile section of Mogadishu, Somalia. But Scott is primarily — some would say solely — a creator of memorable images rather than a storyteller. He isn’t capable of the poetry or philosophy or political context that might lend meaning to what went wrong in Mogadishu. So “Black Hawk Down,” with its cliché-riddled script by Ken Nolan (apparently assembled from loose fragments of other war films), becomes an endless battle scene in search of a movie. It’s every bit as harrowing — and also every bit as pointless and misguided — as the botched military mission it depicts.

Even in Scott’s least successful films (consider also “G.I. Jane” or “Black Rain” or “Someone to Watch Over Me”), his eye for imagery never fails him completely, and there are at least a moment or two of expressive power that defy language and reason. Strictly in a compositional sense, “Black Hawk Down” — shot by Slawomir Idziak, once Krzysztof Kieslowski’s cinematographer — is often brilliant, from its careening aerial sequences over Mogadishu (the dilapidated ex-colonial architecture is actually that of Rabat, Morocco) to the unrelenting nightmare of the street battle between U.S. forces and the militias of warlord Muhammad Farah Aidid. When two American soldiers, lost and perhaps forgotten by their comrades, tiptoe through an empty intersection, they meet a solitary donkey pulling a gaily decorated cart. Deep in the night, when the trapped Americans are beginning to wonder how much worse it can get, we watch one soldier dying of his wounds, as he holds a friend’s hand and tries to say something. All he can get out is: “There’s nothing. There’s nothing.”

Even today, the Oct. 3, 1993 firefight in Mogadishu remains the U.S. Army’s most bitter engagement since Vietnam; 18 Americans died, along with uncounted hundreds of Somalis. (Osama bin Laden, although not mentioned in either the film or the book, was reportedly fomenting anti-Americanism in Somalia at the time.) While the episode seems ripe with both dramatic potential and contemporary relevance, Scott can’t decide whether to make the film a propaganda shoot-’em-up or a moral docudrama, and it ends up as a half-assed neither-nor. If it’s possible to describe a movie as simultaneously gripping and dull, this is that movie. For all its pulse-pounding death and terror, all its blood and screaming, all its slo-mo animation of rocket-propelled grenades in flight, “Black Hawk Down” never gives you the sense that it has an idea in its head or a clear destination.

I can understand why Scott avoided the most mythic and primal image from the Mogadishu battle: the half-naked corpse of Master Sgt. Gary Gordon being dragged through the streets to be kicked and spat on by the very people he was theoretically there to help. All the same, there’s something dishonest about leaving it out. As unpleasant as it might be for Americans to see that image again, it contains a kind of truth that is both literal and symbolic. Like pictures of Ground Zero in New York, it reminds us of things we’d rather not be reminded of, but that we can’t always avoid. It’s not clear — at least, not to me — that we are honoring the memories of Gordon and his comrades, or of the thousands in the World Trade Center, by sanitizing our memories and sugaring our emotions, by thinking only the thoughts about our country that we wish were true.

Trapped between the desire to create a patriotic spectacle and the demands of Bowden’s rigorously researched narrative, Scott and Nolan haven’t served either purpose especially well. On one hand, the film version of “Black Hawk Down,” unlike the book, provides virtually no context for the famine and civil war in Somalia, and presents the citizens of Mogadishu as a teeming, vicious horde, an angry black tide that engulfs the lonely emissaries of civilization. On the other hand, none of the movie’s American characters (some of whom are composites, while others bear the name of real soldiers) amounts to much more than a wisecrack, a typical gesture or an attitude.

There’s the eccentric coffee aficionado (Ewan McGregor), the big, laconic colonel (Tom Sizemore), the legendary shitkicker (Eric Bana), the old pro (William Fichtner), the hard-ass captain (Jason Isaacs), the jovial pilot everybody calls Elvis (Jeremy Piven) and the eager kid on his first mission (Orlando Bloom). I know these characters’ names only because I have the press kit. They’re archetypes — and witless ones at that — rather than people, and the only challenge they establish for the viewer is trying to guess which of them will come home in pine boxes. One of Bowden’s great accomplishments was his portrait of the hidden world of Special Forces, with its culture clash between the straitlaced Rangers and the good-time cowboys of Delta Force, which almost totally disappears in Nolan’s screenplay.

Inevitably, Scott and the producers have attempted to recast “Black Hawk Down” as a story of American military heroism, rather than a grim fable of a Murphy’s-law mission doomed by arrogance, incompetence and sheer bad luck. (I don’t know whether the film was recut after Sept. 11, but I wouldn’t be surprised.) There’s no denying that the men who fought and died for their country that day in Mogadishu were brave: As shown in the film’s most agonizing scene, two Delta Force commandos volunteered to air-drop into one crash site and defend the injured chopper pilot from an armed Somali mob without knowing when, or if, they might get help. (If you’re expecting a thrilling last-second rescue involving Russell Crowe or Keanu Reeves, you’ve picked the wrong movie.) But what were they doing in Somalia in the first place? Why did an entire city seem to rise up in hatred against them? What purpose did their bravery serve?

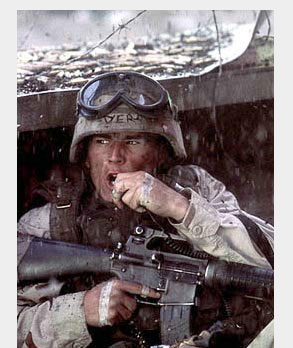

“Black Hawk Down” never answers these questions, or even quite asks them. There’s an awkward bit of exposition early in the film, when a group of young Army Rangers is hanging around their barracks waiting for the fun to start. They begin teasing Staff Sgt. Matt Eversmann (Josh Hartnett) — the closest thing to a main character this overcrowded yet anonymous movie can offer — about his supposed affection for the “skinnies,” as the starving Somalis are known in dark-humor Army-speak. “Look, there are two things we can do,” responds the earnest sarge. “We can help these people or we can watch them die on CNN.” There was a third option, as it turned out: Armed with good intentions and expensive weaponry, we could blunder into a situation we only partly understood, causing a lot of death and destruction and making a bad situation even worse.