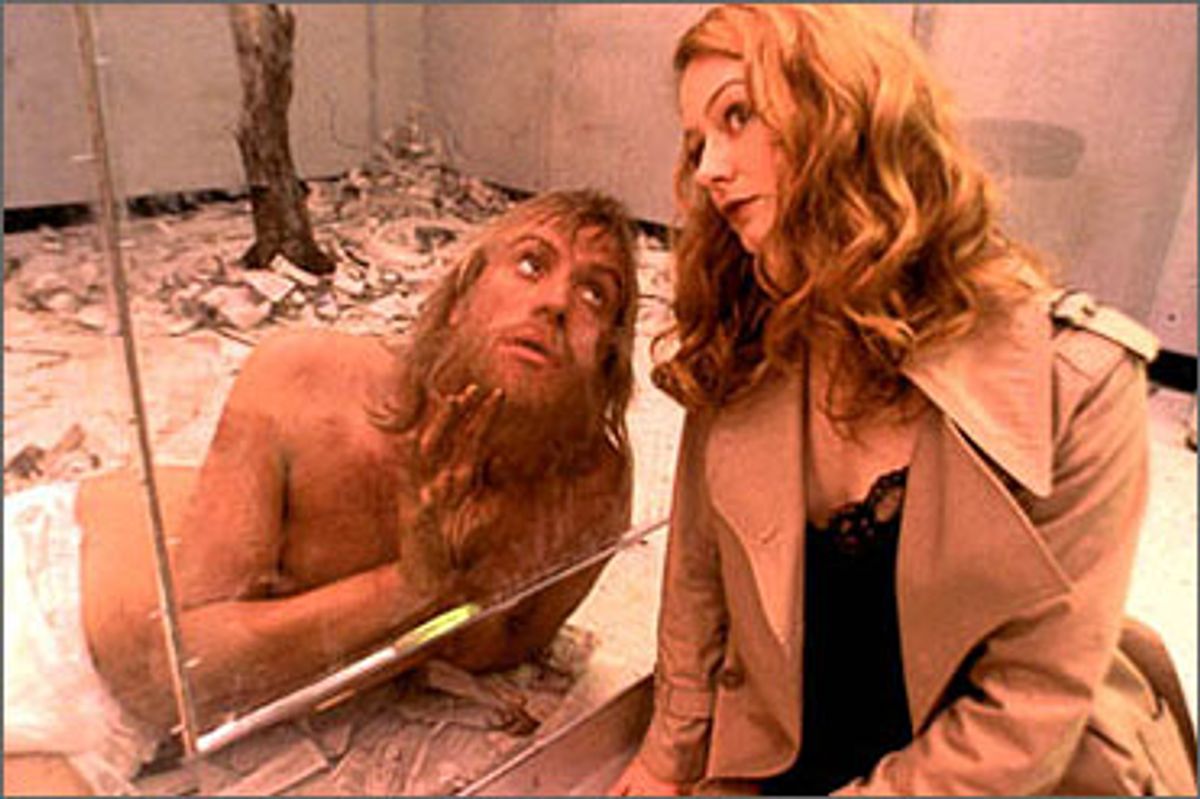

Toward the end of "Human Nature," Nathan Bronfman, the obsessive scientist played by Tim Robbins, tracks down Puff and Lila (Rhys Ifans and Patricia Arquette), a couple he knows who have escaped to the woods to live naked like wild animals. Breaking his vow to avoid language, Puff asks Nathan to define a polysyllabic word that's been bugging him. "It means the inability to perceive things as elements of a whole," Nathan explains. One could certainly contend that screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, the mastermind behind both "Human Nature" and 1999's "Being John Malkovich," suffers from this disorder, whatever it's called. With him, in fact, it may rise to the level of a worldview or a guiding philosophy.

With "Being John Malkovich," his first produced screenplay, Kaufman announced himself as a Hollywood legend in the making. Whatever you made of that film's deranged blend of showbiz satire and minor-key Monty Python absurdism -- and I found it outrageously funny, if finally incoherent -- it was going to be a tough act to follow. Between Kaufman's image as a never-photographed recluse and his high-concept, shotgun-splatter approach to writing movies, you had to wonder whether he was going to succumb to his own mystique before his career path had a chance to jell properly.

"Human Nature" is the funniest movie I've seen so far this year (which is saying almost nothing), but it has an air of pale, forced outrageousness about it that suggests it may be legitimate to question Kaufman's staying power. Much of the humor is old-fashioned slapstick, albeit often irresistibly twisted: Take the scene in which a man outfitted with an electroshock collar keeps flinging himself at a slide projection of a seminude model who strongly resembles Hillary Clinton, undeterred by the ever-higher doses of voltage he receives.

Basically, if you go through a list of the film's freakazoid characters you've set up all the jokes. We've got the woman with thick, dark hair growing all over her body (Arquette, doing some of the weirdest nude scenes in cinema history) who just wants love! We've got the ape-man (Welsh actor Ifans) raised in the wild, who ends up testifying to Congress about "the waywardness of humankind"! (Kaufman adores spoofing that kind of old-fashioned pseudo-profound language.) We've got a repressed scientist (Robbins) with a tiny dick, who is trying to teach lab mice to eat with salad forks! (Admittedly, these scenes, which look distressingly unfake, are among the movie's moments of pure hilarity.) For no particular reason, we'll throw in a sexy "French" lab assistant (Miranda Otto) in thigh-high sheer stockings, who may be a gold digger or just a self-dramatizing femme fatale.

Kaufman and "Being John Malkovich" director Spike Jonze, who serve as co-producers here, have handed off the directing duties to Michel Gondry, who helmed the 1998 French film "The Letter" but is better known for his remarkable music videos for Björk. (Jonze is directing Kaufman's next project, the semiautobiographical "Adaptation," which stars Nicolas Cage as Kaufman himself.) What's odd about Gondry's direction here is how strongly it resembles the unshowy, off-kilter naturalism Jonze adopted for "Malkovich." Much of "Human Nature" has the flat, slightly washed-out look of those films you watched in high-school biology class, an aesthetic that extends to the quavery, tinny score by Graeme Revell.

When we explore the various characters' childhoods -- for a guy whose movies seem more like agglomerations of ideas and images than patterned narratives, Kaufman is awfully interested in psychology -- we go even further into visual kitsch. The screen image shrinks down to sprockety Super-8 for Nathan's first visit to the zoo, or preteen Lila's discovery of her proliferating chest hair or baby Puff being abducted by the schizophrenic father who believes himself to be an ape. (As Nathan's supremely dysfunctional parents, Robert Forster and Mary Kay Place have the retro-Americana snark meter cranked to 11, but as such portrayals go they're amusing.) These flashbacks, like this entire movie, are more confusing than enlightening: Kaufman and Gondry seem to suggest that all four major characters are connected by fate, as in a Greek tragedy, and also that human beings are trapped between the impossible competing demands of nature and civilization.

That's awfully heady stuff for film comedy, and while I applaud the attempt to cram real ideas into absurdist farce, I'm less enthusiastic about Kaufman's resolute refusal to tell a story that makes any sense. People keep going out into the forest (or into the movie's cheese-ola "forest" set) and coming back. That's about it. Hairy Lila goes out and lives in the forest, where she composes an ode to God -- for a moment "Human Nature" threatens to turn into a musical -- and becomes a famous nature writer, authoring a bestseller entitled "Fuck Humanity." Then she hooks up with Nathan, a repressed, borderline sadomasochist who hates nature. (Um, OK, I guess. But these people would get together in real life some decades after hell froze solid.) Then gamine Gabrielle (Otto) shows up and rubs up against Nathan like a kitten, informing him in her fake-o accent, "Ah weel not be your cheapie parlez-vous mademoiselle! You 'ave to choose. Eez like 'Sophie's Choice.' Except eez Nathan's choice."

Meanwhile Nathan is making his reputation by retraining the recaptured wild man (named Puff by Gabrielle, after her alleged childhood cat) to eat with the proper fork, applaud at the correct moment in the opera and, most important, not to hump any available female like a wild dog. Never mind that this plotline makes even less sense than the rest of the movie; the indomitable Ifans, long a master of comic exaggeration, handles the impossible transition from ape to man and back again with tremendous grace.

Indeed, Ifans is the only actor here who seems to understand that you have to play Kaufman's ludicrous scenarios by eating them alive, the way the real John Malkovich did as the posturing, horn-toad title character of Kaufman's first film. As Nathan, Robbins is mostly a gray, worried nonentity; despite his numerous good-faith efforts to prove me wrong, I think he's much better at drama than comedy.

Arquette is asked to do everything here except recite the gospels in Aramaic and revolve her head at 45 RPM like Linda Blair (and I imagine Kaufman considered those ideas too). She's an object of ridicule and of pathos. She's a sexy, self-actualized feminist guerrilla and a depilated doormat in a horrible wig and pink press-on nails. She sacrifices herself for love and is made to look like a chump. It's too much. It's about 10 times too much material for a really good actress, and all Kaufman and Gondry can do here is expose Arquette's limits unfairly.

"When in doubt," Nathan's father advises him, "don't ever do what you really want to do." Despite the obvious ironic tone here, Kaufman isn't some hackneyed Henry Miller-Charles Bukowski figure, overeager to rebel against this rule in all its supposed manifestations. Puff doesn't want to go back to the woods after he learns about poetry and opera (and skanky back-alley prostitutes). Lila's nature-girl act is just as fascistic in its own way as Nathan's clenched-butt view of science. This ambivalence might make for a fascinating Bill Moyers documentary or a ribald comedy of the inevitable collision of ideals and reality in human existence. The problem with "Human Nature" is that it tries to be both and ends up somewhere in the lumpy in between.

Shares