To listen to a podcast of the interview with Sheryl Crow, click here.

To subscribe: Click here to add Conversations to iTunes or cut and paste the URL into your podcasting software:

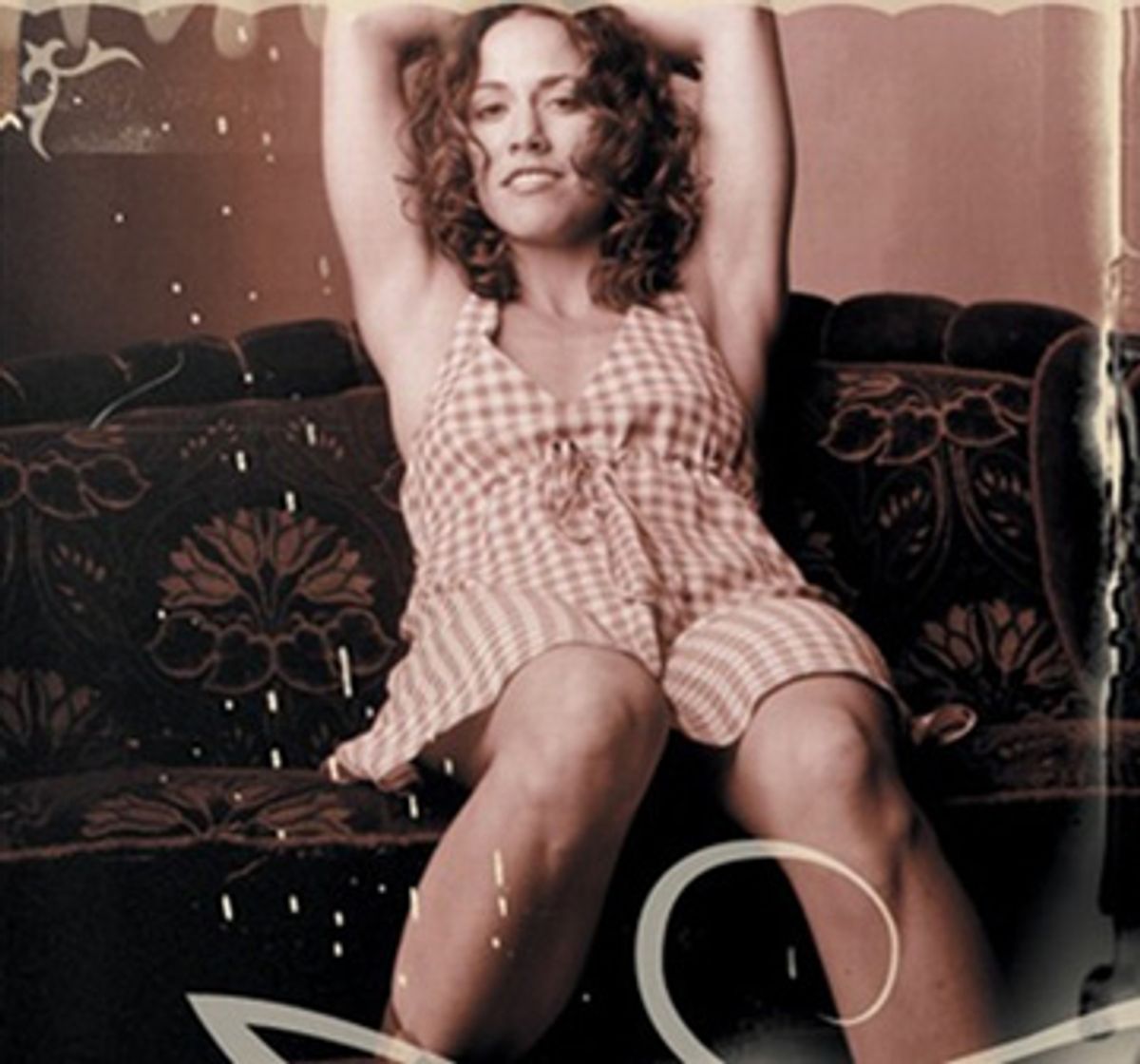

Ever since lodging "All I Wanna Do" in our heads back in 1993, Sheryl Crow has been steadily writing and performing solid, decidedly nonwimpy pop music. Her self-titled 1996 record was bolder and rawer than her debut album, "Tuesday Night Music Club," and garnered the kind of mixed reviews that so often greet sophomore efforts. But the contemplative balladry of 1998's "The Globe Sessions" was greeted with raves. She showed she had friends in high places with "Sheryl Crow and Friends: Live From Central Park" (1999), which included guest appearances from Eric Clapton, Chrissie Hynde, Stevie Nicks and Keith Richards. The sunshiny confection "C'mon C'mon" was released in 2002, followed in 2005 by the more pensive "Wildflower."

A nine-time Grammy winner, Crow has resisted sugarcoating. Back in 1996, a certain big-box retailer refused to sell her music after being named in her song "Love Is a Good Thing": "Watch our children while they kill each other/ With a gun they bought at Wal-Mart discount stores." More recently, Crow has been vocal about her opposition to the Iraq war. And after being diagnosed with breast cancer in 2006, she became known as an advocate for that cause, too. (She has since recovered, and calls herself a "poster child for early detection.")

Apart from her music, these days the 45-year-old singer is perhaps best known as an environmental activist. (She even became something of a punch line after suggesting that people should use less toilet paper.) In the spring of 2007 she and fellow activist Laurie David headlined the Stop Global Warming College Tour, aiming to raise awareness about global warming and put pressure on lawmakers to curb it.

Crow's new album, "Detour" (slated for release on Feb. 5), is meant to be a rousing call to action. Songs like "Love Is Free" and "Peace Be Upon Us" address the current state of the world, from the mess in New Orleans to the war in Iraq. Others like "Lullaby for Wyatt" (named for her young son) and "Drunk With the Thought of You" are more immediately personal. While people bemoan the shortage of contemporary singer-songwriters building on the protest tradition, Sheryl Crow stands out as that rare commercially successful artist who puts political issues at the heart of her music. She spoke to Salon by phone about tying it all together. (Listen to a podcast of the interview here.)

How did you decide what direction to go in with the new record, and how did the concept evolve?

I worked with Bill Bottrell, who produced the "Tuesday Night Music Club" record. I had not worked with him since 1993. The two of us have gone on many detours in our lives that brought us back to this point. We always knew we had a great creative relationship, so it just felt like it was time to get back together. It was really like a homecoming for the two of us. It was a very creative and emotional and intense process. We recorded 24 songs over the course of about 40 days. Conceptually, I think the two of us agreed that the record had to be very raw, and [I was] committed to writing about what's going on right now in the world and also what was happening with me personally. I think most people know that the last three years were very informative and intense years for me, so that had a very heavy impact on the content of the record.

I'd just adopted Wyatt -- he was 3 weeks old when I started the record. Just having him around rendered me completely fearless and unable to edit myself. He sort of made the whole writing process feel more urgent and intense. The lyrics really just spilled out; it was almost like a writing binge for me.

The first single, "Shine Over Babylon," certainly seems meant to fit into the tradition of political songs, and you've described it as being in the tradition of Bob Dylan. What are your thoughts on the relationship between music and social change?

Well, I would love to think that there is a correlation there. I know that when I was growing up -- I was maybe 10 years old when the Vietnam War was coming to an end -- there was an intense social movement of kids who were like 10 years older than me, college-age kids [who] were really taking it to the streets. Young people certainly had a voice at that time, and their musicians brought, I think, a real voice to what they were feeling. We've seen that sort of wane over the last 20 years. We've gotten more geared towards entertainment and away from having artists try to help us [sort out] what was happening socially. I don't know that there's a great impact now, but I like to think that there are people out there who are talking about these very things. I know that in my life I'm surrounded by people who are concerned about the environment and upset about what's happening in the government and extremely disturbed about where we stand in the world theater and where we're being led as a people.

Has it been challenging in any way to integrate your political activism and your music career?

Not at all. Clearly I'm not one of the young kids out there just getting started. I'm not a flavor of the month. Also, I'm older than [the musicians] getting played on the radio. For me it feels like there's a lot of freedom in that, a lot of freedom in being able to talk about what I want to talk about. Not to mention that I don't feel like I have any choice: These are the things that are interesting to me, and that matter to me, and it would be difficult for me to betray myself and not write about them right now.

How did you first get involved in working on environmental issues and global warming?

I started working in the world of the environment when I was out with Don Henley, which was 1991, I guess. He had just basically purchased Walden Woods in an effort to preserve what is considered to be the cradle of the environmental movement. That's where I became very aware of what direction we were moving in as far as the planet is concerned. Then this past spring Laurie David and I did a college tour where we talked about the state of the environment. At that time, people were still trying to debate and argue and even refute the science that's out there. I think in the last six months we've seen an undeniable movement towards having to acknowledge and accept that the science is there, and that our planet, which is a living organism, is truly suffering because of the way we're living.

I'd love to hear you tell the story of your confrontation with Karl Rove at the White House Correspondents' Association dinner back in April.

Well you know, Laurie David and I like to take full credit for him leaving office, but that's probably not exactly accurate. [Laughs] It was a very innocent encounter. Laurie and I had been feeling like we were leading a grass-roots movement of young college kids who were really concerned about what the planet was becoming, what kind of planet they were being left, and feeling a little cheated by it. They were starting to try to find innovative ways to change their college campuses, to try to incorporate a green lifestyle into future work situations. At that time, and even still, the administration was in denial and dragging its feet about doing anything about emissions or just acknowledging that the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] reports were concrete evidence of the demise of our planet.

So Laurie started a conversation with Karl -- or Mr. Rove, excuse me, we're not on such familiar terms -- about the science we have and what the administration was doing. And I walked up, being excited of course about what Laurie and I were doing; it was our first opportunity to actually talk to anybody in the administration. And I guess I walked into a beehive that was already swarming. He was exceptionally rude to the two of us, and at one point he told us both to take our seats. I can tell you how it ended: with me saying, "You can't speak to me like that, you work for me." He said, "I don't work for you, I work for the American people." And I said, "I am the American people." It was a very short and curt conversation.

And probably about as effective as it could be.

Yeah, it was going nowhere from the beginning.

As you traveled around to college campuses on the Stop Global Warming tour with Laurie David, spreading this global warming gospel, what kind of reception did you get from students?

Kind of broad. I think it was a pretty fair sample of how the people around this country are reacting: with disbelief, with fear and panic, and with a feeling of being defeated. [There were also] those people who were feeling like the movement can make a difference, and that it has to be urgent, it has to be the foremost cause of this generation. The interesting thing about college students is that their ingenuity is so without cynicism, and, as we've seen with all social movements that spring from this age group, they have the will and the desire and the belief that they can really change things. The real challenge is trying to incite that kind of momentum instead of feeling that it's too late.

It can be tricky to figure out how to balance being environmentally conscious with the things you do every day. I imagine that some of those adjustments are especially challenging in some of your situations, like putting on big concerts. Have you taken steps to change your energy use in those situations, or change the way you travel?

We're definitely trying to go completely carbon neutral on our tour. On our college tour we [used] biodiesel and we bought carbon offsets. I think a lot of tours are trying to figure out a way to really apply these standards. Guster has started an organization that's trying to go green with tours. My farm [in Nashville] is completely [fueled by] biodiesel, and my cars are all hybrids. One of the things that Laurie and I said throughout this tour is that you don't have to do everything if you just do something, whether it's changing light bulbs, driving an eco-friendly car, not running the hot water, trying not to use your dryer at full-blast heat. Just small, simple things that can make a difference if everybody does them.

Shares