Little Stevie Spielberg is all grown up now — and the results are startling. “Minority Report,” adapted from a Philip K. Dick short story, continues Spielberg’s journey into interior darkness. Both literally and thematically, it follows on the heels of last year’s “A.I. Artificial Intelligence,” in which the little boy — always at the center of Spielberg’s universe — is a robot Peter Pan, a baby emotion-vampire who can never grow up.

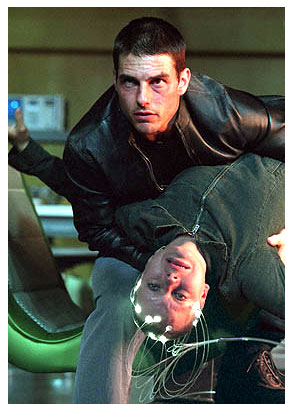

In “Minority Report” the little boy exists only in photographs; he has been abducted by a stranger and presumably molested and killed, leaving behind a tortured dad addicted to mood-altering drugs and happy-family holographic images. This childless father, a Washington police detective named John Anderton (Tom Cruise), becomes a savior of sorts to a motherless child (Samantha Morton) who has been raised as a kind of psychic circus freak, her entire life a series of horrible, screaming nightmares.

“A.I.” was a challenging, intriguing mess, a film that perhaps labored too hard to emulate Spielberg’s idol Stanley Kubrick. (Its reputation, and its significance as a landmark in Spielberg’s career, will grow with posterity.) With “Minority Report,” Spielberg has completed the transformation. And if he will never be Kubrick, he has become fully Kubrickian — a master genre stylist with a surprisingly cold heart. If you really want to be cynical, you might call this the best Paul Verhoeven film since “Starship Troopers.”

“Minority Report” blends the conventions of 1930s film noir with classic modernist science fiction and the more recent dystopian tradition of “Blade Runner” and “The Matrix.” If there’s nothing especially original about the combination, it’s brilliantly executed as pure cinema, both breathtaking and disturbing. Pure cinema, however, is all it is. Steven Spielberg has grown up into, of all things, a superior film artist. He is no longer a social commentator, an observer of contemporary life or a historian, if in fact he ever was any of those things. In the world of movies he’s a grown-up, and maybe nowhere else. You could argue — and probably should — that this limitation will keep him from greatness. Something has been lost and something gained; how you judge the transaction is up to you.

Gone is the so-called childlike wonder of “E.T.” or “Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” which in any case always masked a fear of the dark, a terror at what might lie under the bed. (I have often facetiously argued that the terrifying “Poltergeist,” which Spielberg oversaw but did not officially direct, was his most honest film about American childhood.) Gone, mercifully, is the earnest drudgery of “Amistad” or “The Color Purple.” No one’s going to miss that latter quality, but some critics and viewers are likely to feel that the warm and fuzzy Spielberg is somehow more genuine than the contemporary icy-genius version, and that some fulsome ideal of popular cinema has been sacrificed to phony notions of art, blah blah blah.

I say screw it: Bring on the grimness. No filmmaker has ever needed to get in touch with his inner perversity so badly. Love it or hate it, “Minority Report” brings a cruel and even demonic current that has long flowed under Spielberg’s work to the surface as a rushing geyser. I can hardly wait for the fourth Indiana Jones movie, which Spielberg will reportedly direct for 2005 release. Will Indy, grown too decrepit and cowardly for adventuring, limp through the back alleys of Cairo from brothel to opium den?

“Minority Report” is set about halfway through the 21st century, when the Washington police have established an experimental “precrime” unit that relies on the observations of three psychics, or “precogs,” who are kept sealed off from the world in a swimming-pool unit called the Temple. When the precogs detect that someone in D.C. is about to commit a murder, Anderton uses a kind of heads-up transparent display unit to compose their visions into a coherent picture of victim, perpetrator and setting. His elite team then hits the streets, arriving in a comfortable Georgetown home, for example, just seconds before a wronged husband is about to plunge the scissors into his adulterous wife’s heart.

Cinematographer Janusz Kaminski, Spielberg’s sidekick since “Schindler’s List” in 1993, renders this middle-distance future in watery, muted hues of blue and gray, simultaneously suggesting the precogs’ Jacuzzi visions of homicide and the black-and-white crime films of the ’30s Spielberg has long worshipped. A meddling federal agent named Witwer (Colin Farrell), who at first seems like Anderton’s principal adversary, looks precisely like the federal agent who might be pursuing John Garfield or Edward G. Robinson: He’s got the pinstriped, double-breasted suit in fine broadcloth, the slicked-back hair, the pencil-thin mustache.

The screenplay to this long-brewing project (credited, after a Writers Guild arbitration process, to Scott Frank and Jon Cohen) muddles through some murky passages about how and why the precogs were created and the metaphysical significance of what they do. But they’re not all that central to the future Spielberg presents here, which seems alternately familiar — holographic ads that greet you by name, cereal boxes crawling with maddening animation, psychoactive designer drugs — and like the product of nostalgia for 20th-century futurism, with its vertical cities of glass and concrete, its jet-packs, its electromagnetic cars.

What feels right about the precogs is not the mystical hoo-ha surrounding their visions of murders-to-come but the fact that they make possible a kind of Ashcroftian security state in which individuals are literally imprisoned within their own heads, without trial, for crimes they haven’t (yet) committed. And the precogs themselves, as the briskly efficient Anderton gradually comes to realize, are nothing more than mutant slaves, held in thrall by a techno-Calvinist conception of fate and predestination. When the precogs suddenly present a vision of Anderton himself killing a man he’s never heard of, he has to ask himself that central noir-hero question: Who am I and what am I capable of?

Cruise is generally regarded as an affable action hero without depth, an almost robotic exemplar of American maleness. Anderton isn’t a protagonist who’s likely to engage your passions, but Spielberg has done an admirable job of pulling some deeply damaged weirdness from beneath Cruise’s bland persona. Anderton’s a good cop when he’s at work, but he sits around his sterile hive-like apartment at night inhaling an illegal street stimulant and talking to holograms of his missing son (abducted from a public swimming pool) and the mousy wife (Kathryn Morris) who has drifted off to a Cape Cod-esque retreat rendered in even more washed-out colors than the rest of the film.

When he’s on the run, Anderton seems to wander through a pastiche version of film history, from the city of Fritz Lang’s “Metropolis” through the baroque urban intrigue of “The Big Sleep” and “Chinatown” and the Gothic sci-fi of “Blade Runner.” He ventures into the lair of the geneticist who accidentally created the precogs, and this reclusive genius — who is raising carnivorous flowers in a greenhouse, naturally — turns out to be a woman with a vaguely predatory manner. It’s a nice conflation of various noir clichés (and a terrific cameo for Lois Smith).

In an enjoyable but arguably irrelevant bit of grotesquerie, Anderton undergoes black-market eye surgery (to evade the omnipresent retinal scans) and, like any good noir hero, ends up blindfolded and trapped in a filthy apartment. Also, as the hero of the film, Anderton does not realize until long after we do that Burgess (Max von Sydow), his fatherly superior — following in the footsteps of hundreds of duplicitous Hollywood judges and police commissioners before him — is perhaps not worthy of his undying trust. (“That which keeps us safe,” von Sydow intones, in an infomercial for the precrime program, “will also keep us free.”)

So, yes, much of “Minority Report” plays like a game, but it’s a game whose board and pieces have that slimy, slippery feeling that comes from the underside of the id. When Anderton begins to communicate with Agatha (Morton), the primary precog, whose visions don’t quite conceal a deadly secret, the film gets a bone-sizzling jolt of electricity. To save himself from committing a foreordained murder, he has to pull Agatha out of her womblike tank into a world that can only terrify and disorient her. (He also has to buy her clothes at the Gap, in one of the movie’s more cynically amusing product-placement sequences.)

The connection between Anderton and Agatha, two people who have lost everything important and have only each other, is intensely physical but not exactly sexual; it’s needy and strange and sadomasochistic but still innocent. There’s a distinction between the swaddling comfort of sentimentality — in which Spielberg has long specialized — and the uncontrollable, not-quite-conscious buzz of deeply felt emotion, and this is one of the latter’s rare appearances in his work.

Agatha’s visions are both fallible and reliable: Anderton indeed finds himself facing a man he’s never met before in the predetermined hotel room, and various elements of the movie’s mystery — the fate of Anderton’s son, the role of Burgess, the identity of the murdered woman in an allegedly prevented crime that Agatha keeps compulsively replaying — come into clearer focus. As in all noir films (and this may or may not be a flaw) not all these questions will be answered in the end, and the nature of fate and free will remains as puzzling as ever.

It’s too early to know whether “Minority Report,” on the heels of “A.I.,” marks a brief detour in Spielberg’s career or a permanent change of course, but either way it’s a dark and dazzling spectacle. Even his attempt to craft a resolution to Anderton and Agatha’s stories feels more like an offer of shelter and succor than a happy ending. Adults can survive and adjust, even build anew amid the emotional wreckage of their pasts. But the terrors in the darkness — the boogeymen who tear children from their parents, the nightmares whose details you can’t quite make out — never go away.