About every week or so, you get an e-mail from Barack Obama campaign manager David Plouffe, or top deputy Steve Hildebrand, or maybe Obama himself. They’re breezy and informal, addressing you by first name at the outset (before they ask you to donate money at the end). But that’s just the beginning.

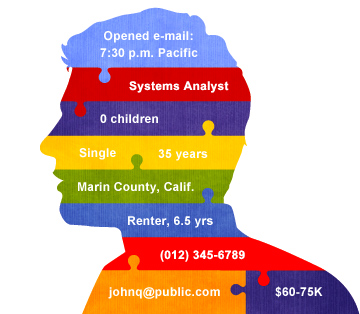

You know, of course, that Obama has your e-mail address. You may not have realized that he probably also has your phone number and knows where you’re registered to vote — including whether that’s a house or an apartment building, and whether you rent or own. He’s got a decent estimate of your household income and whether you opened a credit card recently. He knows how many kids you’re likely to have and what you do for a living. He knows what magazines and catalogs you get and whether you’re more apt to get your news from cable TV, the local newspaper or online. And he knows what time of day you tend to get around to plowing through your in box and responding to messages.

The 5 million people on Obama’s e-mail list are just the start of what political strategists say is one of the most sophisticated voter databases ever built. Using a combination of the information that supporters are volunteering, data the campaign is digging up on its own and powerful market research tools first developed for corporations, Obama’s staff has combined new online organizing with old-school methods of voter outreach to assemble a central database for hitting people with messages tailored as closely as possible to what they’re likely to want to hear. It’s an ambitious melding of corporate marketing and grassroots organizing that the Obama campaign sees as a key to winning this fall.

The sheer scale of the operation — because of Obama’s large network of supporters and heavy emphasis on field organizing — means the data can be sliced in ways that the Bush-Cheney campaign couldn’t have dreamed of in 2004. It’s most likely also more advanced than what either side did in the 2006 elections, or, for that matter, what John McCain is doing now.

All that data gathered in one place may seem a little spooky, though the average credit card company already has it and then some. Ultimately, the approach is about greater sophistication and efficiency. It means the campaign may not wind up wasting time contacting people who are probably voting for McCain, and that when Obama aides or volunteers go out looking for supporters, they have a pretty good idea of what issues those potential supporters care about most. It’s the political equivalent of what big corporate marketers have been doing for years: If you’re a baby boomer living in Westchester County, N.Y., golf gear catalogs will show up in your mailbox, but if you’re a 20-something living in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, you might get a free trial of Spin magazine instead. Now the same goes for politics — if you’re in a demographic that makes you statistically likely to have children, Obama might send you an e-mail about education policy instead of one about taxes.

“It takes getting out the vote from the horse and buggy era to the space age,” said Andrew Rasiej, the co-founder of techPresident and founder of the Personal Democracy Forum, who has advised Democratic candidates on online politicking for years. By collecting their own data, then bouncing it against publicly available information like Census reports, voter registration files and other databases, Obama aides can slice the electorate up almost any way they want.

Neither the campaign or its consultants would offer up many details about the operation; what they have is most likely a mix of hard data and predictions based on statistical models. Some very specific tidbits are available from consumer marketing firms; if you’ve ever registered a product — a TV, a computer or a microwave, for example — chances are the campaign knows you own it. Likewise, they know if you’ve signed up for the frequent customer club at your local Whole Foods, or if you’ve joined the American Civil Liberties Union. (Yes, those last two probably make you an Obama supporter). Or whether you own a gun and have a current hunting license. (An indicator you’re less likely to pull the lever for him in November.)

They can add that to what they know about the neighborhood in which you live — even about your specific block — then run all the information through a computer, and voilà: Obama aides can pull up a list of, say, married white men over 30 from an area where people buy a lot of gourmet potato chips and Miller High Life sells well.

For the most part, no one particular piece of information has an overwhelming Democratic or Republican tilt, though there are a few exceptions. For instance, people who live in “multi-unit dwellings” — apartment buildings — tend to be overwhelmingly Democrats, possibly because that one indicator tends to bring others along, like income, neighborhood density and living in a city.

“People get hung up looking for a silver bullet,” said Ken Strasma, a Democratic consultant whose firm, Strategic Telemetry, worked on more than 100 races in 2006 and is mining data for Obama now. “They want to know, is it cat owners or bourbon drinkers or some nice buzz phrase like that. It’s when you see the interactions between hundreds of different data points [that patterns emerge] — it’s rare that you see one single indicator pop.”

The Obama campaign staff wouldn’t talk about what patterns they’ve discovered among supporters, but it may be that such broad categories as “soccer moms” from races past are being replaced by others as complex as “iPhone owners with master’s degrees in their 40s who shop at Costco and get frequent flier miles for their credit card purchases.”

Republicans have been doing this sort of thing for the last couple of election cycles; George W. Bush’s re-election campaign in 2004 boasted about using consumer data to find new supporters (based on eye-catching pieces of information like whether voters drank whiskey or vodka, which probably came from statistical models, rather than actual surveys). But Democrats mostly used targeting information to help with fundraising, building impressive databases that only tracked wealthy contributors, not regular voters. There were some successes — John Kerry, four years ago, used data provided by Strasma’s firm to find wealthy Republican women in the suburbs who could be persuaded to vote for him because they favored stem-cell research.

Now Obama’s campaign is aiming to be ahead of even the GOP’s standard in applying sophisticated data mining techniques across the board, supported by all the traditional canvassing, door-knocking and other work it’s been doing. The campaign is collecting some of the most helpful data on its own. For example, aides can track what time you open e-mails from them, and if you show a consistent pattern, they’ll start sending them at around that time of day. “The marginal benefit of sending some people an email at 2 o’clock vs. 3 o’clock vs. 4 o’clock might not make sense [at first],” said Michael Bassik, a Democratic consultant with MSHC Partners, the firm that did John Kerry’s online advertising in 2004. “But once you start getting an e-mail list that’s 3 million, 4 million, or 10 million people, increasing the returns for a fundraising e-mail by 5 or 10 percent means additional returns of tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

If you’re one of the 1 million people who have a login on Obama’s social networking site, they know how often and when you visit, and they can use that to gauge how committed you are to the campaign. A few months ago, the campaign sent out a three-page survey asking people about their voting habits, how often they go to church, which groups and issues they identify with and whether they’ve given money to political candidates in the past. The point of all of the online gadgetry is to get people to show up for offline events. “We’ve tried to orient the tools less as a social network and more as a mobilization network,” said Joe Rospars, Obama’s online director. “We’re creating opportunities for people to get out there and do things — the campaign is election-outcome oriented.”

Offline, volunteers are canvassing neighborhoods where they think they’ll find supporters, or getting contact info at Obama’s big rallies, picking up chunks of similar data. Unlike with previous campaigns, Obama’s aides dump all the information they get into one centralized database. So if you give the campaign $50 from an online solicitation, then show up at a rally organized offline, the campaign knows that. Likewise, if you join Obama’s Facebook group (approximately 1 million strong), then later buy an Obama ’08 umbrella, aides file that away for possible use later.

That’s part of what makes the Obama effort different from, say, Howard Dean’s 2004 campaign, which raised (for back then) impressive amounts of money online and built a large e-mail list but never really integrated everything into one system. Now, Obama isn’t letting any pieces of potentially useful information go uncollected. “It’s not an innovative campaign, but it’s an extraordinarily professional one,” said Zephyr Teachout, who ran Dean’s online organizing. “They’ve taken all our stupid ideas and made them smart.”

But they’ve also taken all of Capital One’s ideas and put them to work. It seems Joe McGinnis had it right 40 years ago, when “The Selling of the President” chronicled how techniques from Madison Avenue helped send Richard Nixon to Pennsylvania Avenue. If Obama wins the White House in part by looking at voters the way corporations look at consumers, by 2012 it may be even harder to tell where politics ends and marketing begins.