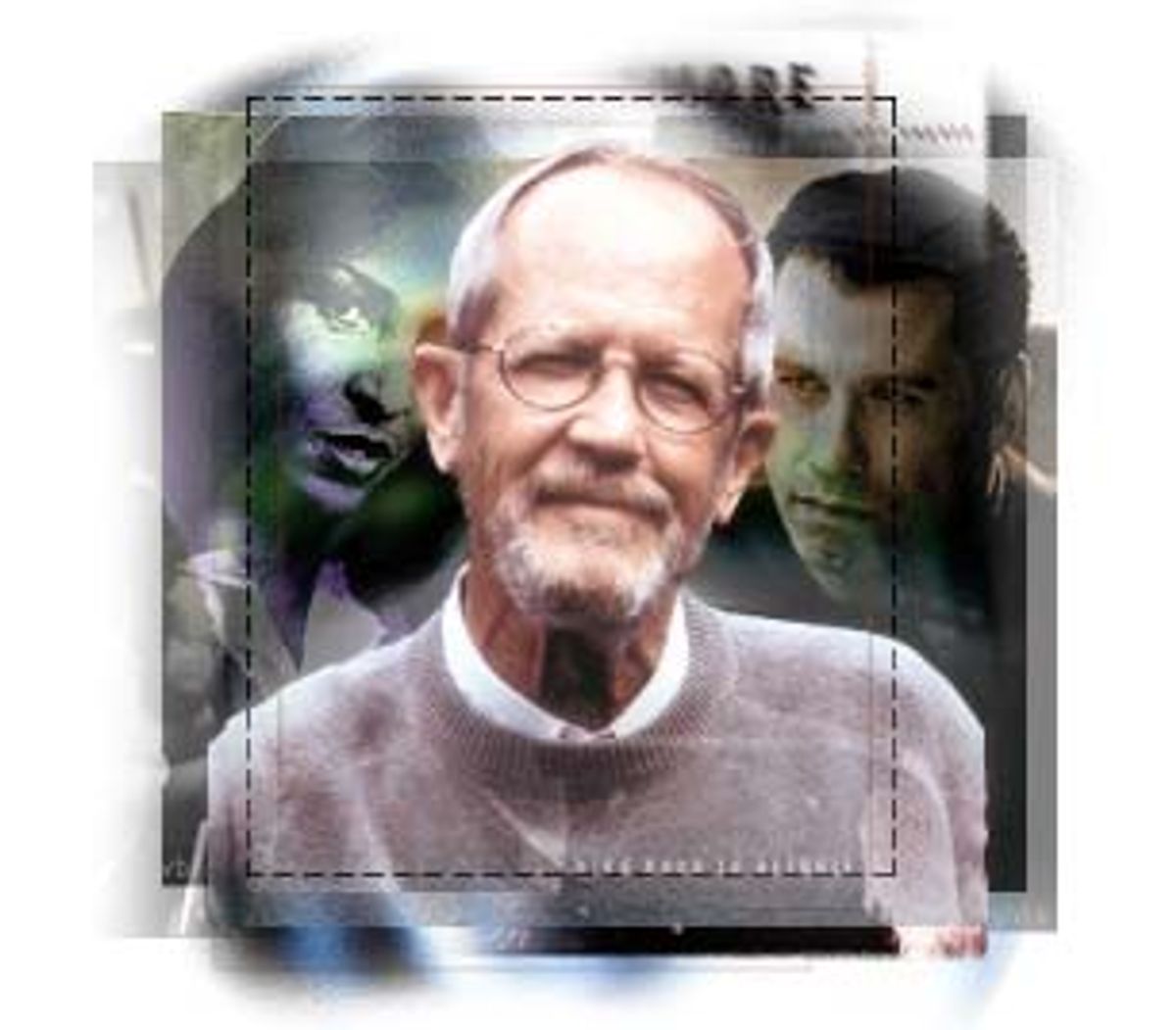

Everyone in Hollywood loves Elmore Leonard, at least that's what they all say. Ever since the critical and commercial success of Barry Sonnenfeld's 1995 adaptation of Leonard's bestseller "Get Shorty," and the critical success, at least, of two other Leonard films (1997's "Jackie Brown" and 1998's "Out of Sight"), actors, producers and directors have all been taking the stand. I love Dutch, they say, using the nickname his friends all use. Read all his books -- all 35 of them. And given the addictive quality of Leonard's tight, seamless prose and the page-turning pull of his crime stories (he wrote westerns early in his career), some of them may even be telling the truth.

Seldom mentioned is the fact that all but a handful of his books have been optioned for the screen and that most of those that have been adapted have been awful. Setting the tone, Warner Bros. made a movie of "The Big Bounce" (1970) based on the author's first crime novel and starring that beefcake of a bygone era, Ryan O'Neal. In a 1997 interview in Good Housekeeping, Leonard recalled going to see it in a theater at the time. "About 15 minutes or so into it, the woman sitting in front of me turned to her husband and said, 'This is the worst picture I ever saw.' And I agreed with her wholeheartedly and all three of us got up and left."

"Elmore has this ability to write books that seem like treatments for movies," producer Walter Mirisch ("The Magnificent Seven," "West Side Story") said of Leonard. "That's why he's so popular here." But until "Get Shorty," most film versions of Leonard's books were curiously free of the very characters that inhabit his stories, as if someone had dropped a neutron bomb on them, leaving only the trappings. Scott Frank -- who wrote the scripts for "Get Shorty" and "Out of Sight" and is working on the film adaptation of "Be Cool," the sequel to "Get Shorty" -- thinks he knows what the problem is. "Oftentimes, with his books, people misunderstand where the gold lies," Frank told the Los Angeles Times. "And what they do is keep the plot and jettison all the textural things -- the characters, the dialogue -- all that goes. And the plot -- even he'll tell you it's insignificant. You have to start with those characters and that may mean reinventing some of the plot."

You want to reduce it to a sound bite ("It's the characters, stupid") or invoke some old Hitchcock business about the MacGuffin, but it's a little more complicated than that. Leonard's characters are mostly involved in crime or law enforcement, but there is very little that's black-and-white about them. The people on the side of the law (cops, judges, lawyers) are frequently dirty themselves while his criminals (those who aren't outright idiots, sociopaths or drug addicts) are often quite complicated. He has brought matters of conscience to genre fiction, putting questions of race on the front burner in his westerns, and has written more authentic female heroines in his crime books than any other contemporary male author I can think of, regardless of genre. And though dark currents run through Leonard's books, his touch is light, often comic, and the pop culture references are smarter than those made by most writers half his age.

The people in his books are always talking, it seems. "Are you coming on to me, Elaine?" Chili asks a movie producer pal of his in "Be Cool," to which she replies, "I'm making conversation."

"When did we ever have to do that? We can talk nonstop any time we want." And so it is for most of Leonard's characters: They tell jokes, they tell stories, they talk shit, often of a professional nature. "I sort of let my characters audition for me," he has said. "I listen to them and let them do all the talking." Though Leonard did a lot of reporting early on -- hanging out at a homicide squad room in Detroit for "City Primeval" (1980), for instance -- and now employs a full-time researcher, he does not repeat or mimic what people say. "The main thing with my dialogue is the rhythm of it -- the way people talk, not especially what they say." The magic of what he does, the part many writers wish they could mimic, is that he makes you care about the characters he creates before you even realize it. It is a talent born of character, yes, but also of work and frustration, of sobriety and loss. The love scenes in his books almost always work; they remind you what it's like to fall in love. And when bad things happen to good people, when characters you've come to grow fond of are killed, often before your very eyes, it seems shocking and unfair. Just like in real life.

Nothing to it. If changing your life was this simple, why was he ever concerned about the everyday stuff, writing fifteen thousand criminal offenders? He said to Jackie, 'Okay,' and was committed, more certain of his part in this than hers. Until she stood close to him in the kitchen and he lifted the skirt up over her thighs, looking at this girl in a summer dress, fun in her eyes, and knew they were in it together.

-- From "Rum Punch" (1992)

The middle-aged romance of bail bondsman Max Cherry and flight attendant Jackie Burke (nicely brought to life by Robert Forster and Pam Grier in Quentin Tarantino's "Jackie Brown") is a testament to the author's belief in second chances and second acts, Fitzgerald be damned. So it is that certain characters of his reappear in his books, as though one turn upon the stage were not enough. There is Max and Jackie's nemesis, Ordell Robbie and his sorry crew (last seen in "The Switch"); Harry Arno, the hapless bookie of "Pronto" and "Riding the Rap," and Raylan Givens, the steadfast U.S. marshal of the same books; and Chili Palmer, the shylock cum movie producer of "Get Shorty" and "Be Cool." (More on him later.) "I'm writing about the kinds of people that interest me the most," Leonard told Good Housekeeping, "savvy people, people who have a hustle going."

Leonard's hustle has always been writing -- not the easiest way to make a living, granted, but a mostly honest one. His family settled in Detroit in 1934 when Elmore was 9; his father was an executive for General Motors, and his relatively privileged position spared the Leonards the worst effects of the Depression. It was that year that Elmore saw the film version of "All Quiet on the Western Front," based on Erich Maria Remarque's classic anti-war novel, and wrote a play in homage which he performed in his Catholic fifth-grade class. To this day, Leonard approaches violence gingerly, almost reluctantly, in his work. Take this prelude to a fight scene in "The Big Bounce":

It was coming now and Ryan knew it. Every time he had ever been in a fight since he was little, he knew this time when his stomach tightened and he could see in the other guy's eyes they were going to go through with it. He had thought about it a lot, this moment, and he had come to realize the other guy must be feeling and thinking the same thing ...

Leonard is often mentioned as the heir to Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett, but Hemingway is his most obvious influence -- in style, at least. "I'd open 'For Whom the Bell Tolls' and start reading anywhere for inspiration," he told the Guardian in 1998. "I loved his work -- the short dialogue, all that white space, his constructions, his use of participles. I realized that I didn't share his attitude. He took himself too seriously."

Poor eyesight kept Leonard out of the action during the Second World War; as a store manager of the SeaBees he spent the duration doling out beer to sailors on an island in the South Pacific. Upon return he enrolled in the University of Michigan where he majored in English and philosophy. He began working for an advertising agency in college, an experience he claims taught him nothing as a writer. He was already writing short stories when he started "writing cute" for clients like Chevrolet ("I could do truck ads, but I couldn't do convertibles at all," he told Martin Amis, one of his many A-list author fans). Argosy, that venerable standard-bearer of hairy-chested prose, published Leonard's first story, "Trail of the Apache," in 1951. He continued to crank out western stories for the pulps and wrote his first novel ("The Bounty Hunters," published in 1953) between the hours of 5 and 7 in the morning, before heading off to work. (His dedication to his craft remains daunting: When working on a book he writes every day, 9:30 to 6, longhand, producing a novel a year.)

But the sales of his western books and stories (two of which, "The Tall T" and "3:10 to Yuma," were adapted for film) were not enough to allow him to quit his day job. His wife, Beverly, and he had five children who recall him toiling away in the basement, surrounded by balled-up sheets of yellow paper. The western market was dying when he wrote "Hombre" in 1960; a film version, starring Paul Newman, appeared in 1966, but the years in between were lean, mean and rather drunken. Leonard was writing scripts for educational films, and there must have been times he felt he'd lost the thread, that his chances were all played out. He would use that sense of desperation to inform his characters' choices in his crime fiction, and the dark undertow of alcohol is felt throughout.

Voted by the Western Writers of America one of the 25 best westerns ever written, "Hombre" reads like a dream -- and I don't mean that the writing is angelic or high-flown. The feel of the book is stark and inevitable, with a handful of characters thrown together in harsh relief against an arid desert landscape: "Stagecoach" as depicted by di Chirico. Despite its concessions to the dime-novel audience ("If there's anything anybody wants to skip, like innermost thoughts in places, just go ahead"), "Hombre" confronted racism head on. Its titular hero (aka John Russell, a horse-breaker of white, Mexican and Indian background) is shunned by his fellow passengers -- until they need him for their survival. And his ultimate sacrifice (a definite bummer for mid-'60s movie audiences) is as puzzling and moving as Billy Budd's, without the Christian overtones.

But by the end of that decade the western was as dead as old John Russell, whereas crime books were back in vogue. "Also, in the western, I had begun to feel as though I were in second gear," Leonard later reflected. "I wasn't using everything around me." The book that became "The Big Bounce," a Cain-like story of a pair of drifters without much of a center, was rejected 84 times, even with the efforts of Hollywood agent H.W. Swanson (who had handled Hemingway, Fitzgerald and Chandler). The book finally sold for six figures, and Leonard said goodbye to ad work for good.

But even as he honed his skills as a crime writer (you can't really call his books mysteries) in the '70s, Leonard's personal life was at sea. In the wake of his divorce from Beverly, Leonard quit drinking in 1977 and began going to AA. Friends describe the sober Dutch as quieter, more introspective but also more attentive. Though by all accounts a happy, voluble drunk, he relearned (like a lot of people in recovery) the importance of listening. One of the people he listened to was his second wife, Joan Shephard (they married in 1979), who read his books in manuscript and campaigned hard for Leonard to develop his female characters. Women in his early crime books often fall into predictable hardboiled categories -- ditzy dame, femme fatale -- while many of the post-Joan novels boast strong, independent female characters, from the defiant defense attorney Carolyn Wilder in "City Primeval" (1980) through the quick-witted probation officer Kathy Baker in "Maximum Bob" (1991) to the revolutionary sympathizer Amelia Brown in last year's "Cuba Libre." When Joan died, suddenly, of cancer in 1993, Leonard must have felt unmoored. (He remarried shortly thereafter.) But in the books that followed there is a sense of regeneration rather than one of defeat. Starting over, Leonard's characters know, is the real American dream.

Tyler felt himself waking up from what had been his life among cowhands and convicts, neighbor to reservation people once nomads, on occasion visiting bartenders and whores who passed for old friends. It seemed a thinly populated life to what he saw here, this mix of people and sounds and colors in a place he imagined Africa might be like.

-- From "Cuba Libre," 1998

"Cuba Libre" was both a return to the western and a new direction for Leonard. Set in Cuba at the beginning of the Spanish-American War, it combined his love of American history with his affection for cowboys and guerrilla warfare and a good old-fashioned triple-cross involving a bag of money. It also gave us, in the character of Amelia, a heroine worthy of her circumstances. She witnesses atrocities and is goaded into revolutionary action by a native fighting the Spanish dons: "Use what you have already seen to hold your anger where you can feel it and that way you don't become so scared. You want to be in this war, come with us." She does, with a vengeance. Though critics were divided on the book, it zoomed to the upper reaches of the bestseller list and has, of course, been optioned for the screen, with Ethan and Joel Coen working on the script (though not committed to directing).

Leonard has been golden since the crossover success of "Glitz" in 1985 (every one of his novels has been on the bestseller list since then), and as good as that book is, it was part of an amazing run that began with the 1980 "City Primeval," still considered by many to be his best book. It is here that the western and crime genres truly flow together (in a moment of overemphasis, Leonard even subtitled it "High Noon in Detroit"). Though the story is touched off by the murder of a crooked judge in inner-city Detroit at a time when that city held the nation's per-capita homicide record, it is really the tale of two men -- detective Raymond Cruz and the "Oklahoma Wildman" Clement Mansell -- at opposite ends of the legal spectrum. Though this is a theme that has been played out in countless cops-and-robbers dramas (see "Heat," et al.), Leonard does not cloud his tale with the code of the West. Setting the standard for Quentin Tarantino, "NYPD Blue's" David Milch and countless other crime enthusiasts, Leonard told his tale with the language of the city, part law-enforcement nomenclature and part street jive. Take this passage of pure Dutch: It is exposition handled with the dispatch of a police report:

In his statement Gary Sovey, twenty-eight, explained how his car had been stolen the previous week and how a friend of his happened to see it in the evening in the parking lot of the Intimate Lounge on John R. Gary said he went over there with a baseball bat to wait for whoever stole it to come out of the lounge and get in the car, a '78 VW Scirocco. Gary stated that he waited in the vicinity of Local 771 UAW-CIO headquarters, which is between the Intimate Lounge and the American La France Fire Equipment Company. At approximately 1:30 A.M. he saw the Silver Mark VI traveling at a high rate of speed south on John R with a black Buick like nailed to its tail. He heard tires squeal and thought the two cars had turned the corner onto Remington. He was on the north side of Local 771, in other words away from the American La France parking lot, so he didn't actually see what happened. But he did hear something that sounded like gunshots. Five of them that he could still hear if he concentrated. Pow, pow, pow, pow-pow. About a minute later he heard what sounded like a woman screaming, but he isn't positive about that part. Was he sure the black car was a Buick? Yes. In fact, Gary said it was an '80 Riviera and he would bet it had red pin-striping on it.

Factor in the torrid couplings of Cruz and Mansell's attorney, Carolyn Wilder; keen observations on race prejudice in all its black, white and brown hues; a mad wild card in the form of some angry Albanians; and a plot line that runs like a lit fuse through the narrative, and you have a book that any other author could have retired on. Makes you wonder what kind of movie Hollywood will make of it.

Despite the injuries the film business has done to Leonard's books, the author remains optimistic about the fate of the rest (Tarantino has optioned three other titles, and Leonard's old pal Walter Mirisch owns the rights to "La Brava"). While Hollywood is the altar some writers have sacrificed their talent upon, Leonard entered into the arrangement with his eyes wide open. He always wanted his books to be made into movies, and he spoke film's language before any director had heard his name. Still, he has learned from his interpreters as well: Tarantino put the racial issues that color Leonard's books front and center in "Jackie Brown" by making Jackie black, while Sonnenfeld turned up the comedy in "Get Shorty" without losing the truth of the tale. "That was one of the things that took me 10 or 15 years to learn," Leonard said, "to loosen up and let this kind of humor seep into the books, and not be so serious about crime."

"Be Cool" is the first book he has written that he knew would be made into a film and it is, alas, not his finest work. Chili's forays into the music business are believable enough (what makes Hollywood Dutch country is that people can be who they say they are there), but the story seems tired, a virtual rehash of "Get Shorty" without the affection the author clearly felt in that book for B-movie legends-in-their-minds like Harry Zim or tragic Hollywood wannabes like Chili's opposite number, Bo Catlett. Chili and Catlett -- one a loan shark, the other a drug dealer -- are both self-made and want to play the movie game, but Catlett makes the mistake of believing his own bullshit. "That's how you tell the good guys from the bad guys," Leonard once said. "To me, the good guy is the one who's natural. He's cool in that way; he's not playing a role. The bad guys are all playing roles, wanting to be somebody else."

John Travolta is the seeming engine driving the sequel, and more power to him. Chili Palmer is the best role of his career, savvy and streetwise but with a sense of humor about the effect he has on others. (Think of him uttering the film's signature line, "Look at me"; it's enough to make you want to look his way.) And though the formula of both "Get Shorty" and "Be Cool" is fish-out-of-water (gangster as movie producer, gangster as music promoter -- the latter not being that much of a stretch), Chili is a classic Leonard hero, at play in a world of new possibilities. The rules of his gangster world are the same as they are in Hollywood: Awareness is paramount and the smartest man -- or woman -- wins. (Drug and alcohol abusers, like Louis Gara in "Rum Punch," don't fare well in Leonard's world: Losing your edge can be fatal.) But more important than winning is enjoying the ride. Asked what he knows about the music business in "Be Cool," Chili takes a guess. "I have a hunch," he says, "there aren't any rules to speak of. You can go for whatever you can get away with, threaten a couple of times to walk out and see if they'll throw in some perks."

Chili could be talking about some other racket in some other town, of course: gambling in Vegas or smuggling in Miami. Leonard is one of our most democratic writers; his stories are not confined by geography or class. Maybe that is why he still has our attention, why after all these years we still look at him: The man is listening to us.

Shares