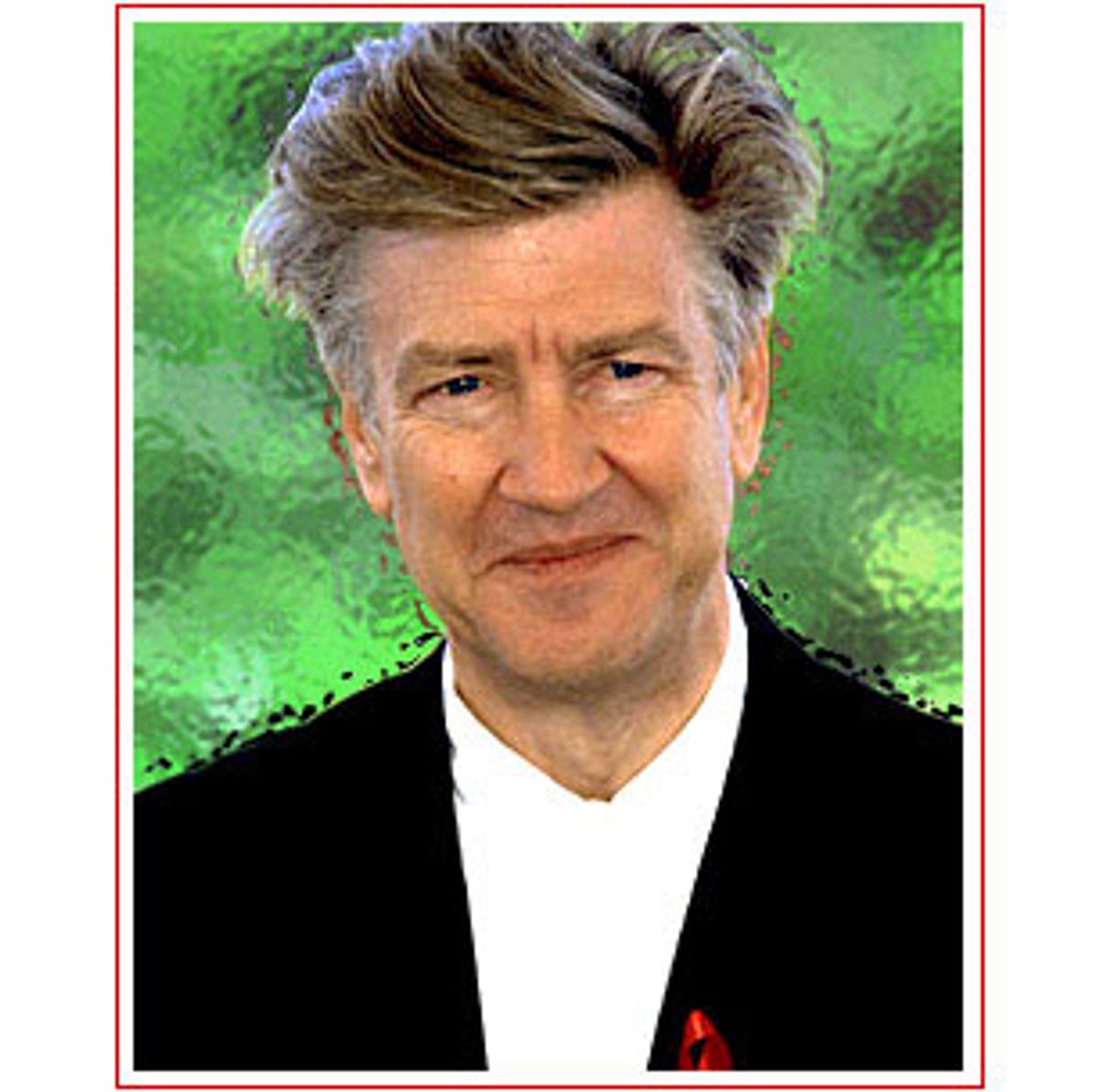

I know where David Lynch lives -- a three-piece concrete compound in the Hollywood Hills -- but I can't describe the layout. When I arrived on Friday morning I inadvertently went up a back stairs and ran into him and two assistants in a kitchen, where he was getting his necessary coffee. We swiftly moved into not a carport, but what I would call an art-port -- a cluttered office next to an open-air studio for painting. He is currently working on a diptych; his materials include abused baby dolls.

The instant impression Lynch gives is a mix of intensity, kindness and enthusiasm. With fingers fluttering like an ant's antennae (as if responding to vibrations at his core), he immediately begins to talk about his predilection for minimalism, and his belief that abstraction in movies intensifies an audience's participation. That belief bleeds into his conversation, where he loves to use words as simple as "thing" and as cosmic as "beautiful." I don't think he's coy or evasive, and when he exclaims "That's great!" for anything that delights him, whether a clear day or a fresh cup of coffee, it isn't a put-on. He wants to protect his own sublime feelings and communicate them to you without vulgarizing them. Watching Lynch gesture with his hands is the aesthetic equivalent of seeing Carlton Fisk nudge his left field shot into home-run territory in Game 6 of the '75 World Series.

Similarly, Lynch's buttoned-up white shirt and rolled-up chinos seem less a trademark outfit than a way of deflecting attention from anything except art and the potential materials for art. When he's engaged he's like a human tuning fork -- he must sense my sincerity when I tell him that I love the subject of our conversation, his latest film, "The Straight Story." It's based on the true tale of Alvin Straight, a 73-year-old resident of Laurens, Iowa, who in 1994 hitched a makeshift trailer to a riding lawnmower and trekked over 300 miles to see his estranged brother in Mount Zion, Wis. Lynch's treatment of the material is open and multilayered; his teamwork with his star, Richard Farnsworth, is empathic and total. Together they have made the rare "movie for all ages" that's also a movie for the ages. It's more about the importance of acquiring wisdom than dispensing it -- even for Alvin Straight, who's lived three score and 13 years.

Farnsworth, now 80, gives new meaning to the phrase "face value": Entire silent epics pour out of his eyes. And that mature enfant terrible Lynch, now 53, knows just what to do with them. Like Lynch's darker, weirder dreams -- say, "Blue Velvet" or TV's "Twin Peaks" -- "The Straight Story" gives off the thrill of discovery from the get-go. Anyone sensitive to mood, sound and sensation, and to the complex presences of Farnsworth, Sissy Spacek as Alvin's daughter Rose, and Harry Dean Stanton as his brother Lyle, will find themselves shaken and honestly uplifted. "The Straight Story" is a testament to following one's own light to the end -- and making movies the same way.

Of course, legends have sprouted around Lynch's roving individuality. How he bopped around from state to state as a kid (his dad was a research scientist for the Department of Agriculture) and from art school to art school as a young adult. How a traumatic stint of urban life in Philadelphia while attending the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts affected him as profoundly as child labor did Charles Dickens. And how, for five years, he turned the stables at L.A.'s American Film Institute into his living quarters and the studio for his debut feature, "Eraserhead" (1976). No director alive has a more distinctive signature than the man who went on to make "The Elephant Man" (1980), "Blue Velvet" (1986) and "Twin Peaks" (1989) -- popular masterworks with a nonpareil mix of fabulism, eroticism, terror and cheek.

But Lynch is the first to tell you that much of his art derives from inspired collaboration. "A lot of the time, life is combos," he says when reminiscing about his late pal Alan Splet, the genius sound designer of his major films up through "Blue Velvet." "The Straight Story" is no exception. To name the most obvious and important example: The woman who found the story, then co-wrote, co-produced and edited the movie is Mary Sweeney, Lynch's longtime companion. Continuing the movie's family theme, Lynch was happy to be able to invite his parents to the premiere of this film, and his kid sister, too, a financial advisor in Coronado, Calif. (His younger brother was busy in Washington state, where he's responsible for the electrical wiring in prisons.) "My mother and father were not allowed to see most of my films -- actually, I think my father has seen all of them, and that the last one, 'Lost Highway,' really disturbed him."

Now that a proposed wild L.A. noir for ABC TV, "Mulholland Drive," has gone into limbo, Lynch has been devoting himself to painting and to making music with his "Straight Story" sound mixer, John Neff, in an elegant studio down the hill from his painting digs. The painting and the music-making are for Lynch catalytic and elating activities that won't necessarily produce anything for public consumption. "I'm not a musician, but I love the world of music; I play the guitar but I play it upside down and wrong-way," he says. "But the music talks to me, does something good for me, and it's good to work with John; we've almost got 10 songs. Like the painting, it could go somewhere but that's not what it's about."

Lynch doesn't see many contemporary films -- "sometimes they just seem to be, you know, what they are." But he's reading "A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies" (the book that came out of the director's idiosyncratic documentary series) and Antoine De Baecque and Serge Toubiana's Truffaut biography ("a great book -- I can't believe Truffaut's early life"). And he says "there are films I would see every other day if I had the time: '8 1/2,' Kubrick's 'Lolita,' 'Sunset Boulevard,' 'Hour of the Wolf' from Bergman, 'Rear Window' from Hitchcock, 'Mr. Hulot's Holiday' or 'My Uncle' from Jacques Tati, or 'The Godfather.' I want a dream when I go to a film. I see '8 1/2' and it makes me dream for a month afterward; or 'Sunset Boulevard' or 'Lolita.' There's an abstract thing in there that just thrills my soul. Something in between the lines that film can do in a language of its own -- a language that says things that can't be put into words."

In the script to "The Straight Story," which has just been published, there are a lot of what seem to be obvious "movie" scenes that aren't in the finished film -- scenes, say, of police stopping Alvin, or of Alvin having a hard time maneuvering because of his physical ailments.

A film isn't finished until it's finished. It's always talking to you, and it's an action and reaction thing all along, to the first perfect answer print. You add a part, and suddenly something else is affected. So it never fails that some of the scenes you think will never go are gone -- and another thing that didn't seem so important, even a fragment, is saving the day.

One thing everyone should do before they say their film is finished is see it with, probably, 20 people or more (although it could just be one person). Your objectivity comes roaring back in because you're seeing it through their eyes now and that can save your film. It's a critical screening, to test it -- and you don't have to have cards filled out, you just have to sit with it and feel it and you'll know what to do. Now, that's a rough screening. The film is working, and working, and all of a sudden it's not working. You can feel it even with people who've gone through the film with you, just from being in a roomful of people.

What gets me -- and I've been thinking about this -- is that the film is always the same when you've finished it. You know, there are variations from theater to theater, in the acoustics and in the brightness (because of the bulbs in the projectors), but the frames are all there, and the sound goes with it. Still, every screening is always different from one to another. This dialogue between audiences and picture is a fascinating thing. Circles seem to start going between them. The more abstract the film, the more audiences give -- they fill in spaces, add in their own feelings. You have the same picture but a different result because of the mix in the crowd. In that way the film is never really finished.

When Alvin finally arrives at his brother's house he hollers "Lyle" twice -- once he just calls out, the second time he sounds worried, like he fears he might have come too late. I just lose it when I hear that second time. It seemed to me like the sort of inspiration that happens with the director and the actor on the set. Sure enough, the script just has one "Lyle."

These things are gifts, in a way. When something just happens that's normal like that, it's so beautiful. What kills me is when Richard does this -- [Lynch inhales sharply, in a strangled sob] -- before the very end. I go crazy when I hear it. I would start crying in the editing room, standing behind Mary when we were working. I think the film really affects men. There's a thing about grandfathers and fathers alive in it -- and brothers, too -- and it gets you. It gets me.

Your father was a research scientist for the Department of Agriculture. You were born in Missoula, Mont., and lived in Sandpoint, Idaho; Spokane, Wash.; Durham, N.C.; Boise, Idaho; and Alexandria, Va. Your background wasn't too distant, geographically, from the people in this movie.

My dad was talking to Richard at the premiere, and they've heard of a lot of the same people, and know at least some of the same people. Richard spent a lot of time up at Glacier National Park at one point in his life, and that's a place where I went as a kid, there and all through the Pacific Northwest. It wasn't part of a cowboy life for me, but it was for my father, a generation before. He rode a horse to school -- a one-room schoolhouse, that kind of thing. My granddad wore cowboy boots and was a wheat rancher and to me was just the coolest guy. Very cool. He would wear these really beautiful Western suits -- and string ties and cowboy boots, really polished. He always drove Buicks. And he wore these special gloves, real thin leather gloves, when he drove. And he drove really slow -- which I really loved. I hate riding fast. Sitting with my grandfather I got a lot of feelings I would never be able to articulate. But small children can feel so much, and they don't forget. And this goes in the bank -- these relationships you have that are pretty profound but are never really spoken.

Your granddad's loving Buicks, and Alvin Straight's attachment to his Rehds and John Deere riding mowers -- they're not exactly the same thing, but they seem linked. You've said the film is about man and nature, but it's also about man and his machines.

I've got pictures of my grandfather and his tractors, with these giant metal wheels and these big spikes sticking out of them, and he and his men with these giant canvas gloves and oil cans, and the scene looks more like a machine shop than a farm or a ranch. These machines were incredibly important to them.

And these machines, like the ones in the movie, have character. Something that has disappeared from contemporary design, which makes everything look the same.

Yes, the character of the machine is gone. I don't know when it happened, but it probably goes back to computers -- when manufacturers started to design everything to be aerodynamically correct, and to use vacuum-formed models and everything like that. You can see why they did it -- it makes perfect sense, and in some ways it's safer, and it could be really good. But then you see a 1958 Corvette Sting Ray, and you almost die to see what it was and what it's come to. You don't have any joy ever getting in a car, not the same joy anyway. There might be some cars that are still pretty cool but they're few and far between. I've got a 1971 Mercedes that is pretty beautiful, a two-door; I'm waiting to get an American car that I would love to drive, but it hasn't happened.

In the film it's not just cars or Alvin's mowers. It's Alvin and his daughter Rose sitting by the humming grain elevators at night, this gorgeous looming image. You provide a feeling for the rural landscape that isn't conventionally soft or pastoral.

It's not like you picture Pittsburgh in the smokestack-industry days -- it's not about belching fire. But these people rely on a lot of machinery, and some of it's huge. When you go to a big John Deere dealership and see what's there, it's pretty impressive. And then there are these big grain elevators, and a lot of railroad tracks right next to them -- it's an industry. But then it's also so organic. It's miles and miles and miles of fields and very few people. What you really feel is man and nature.

You mentioned that the film "talks" to you. How does a script talk to you?

When you read a script or read a book, you're picturing it and feeling it and being moved forward with it. A whole bunch of things start happening inside and those are what you have to remember and translate into film. One moment the idea doesn't exist for you, the next moment that idea comes into your conscious mind and explodes and you know the whole thing. Mary heard about this trip in 1994 when the press covered Alvin's journey. Millions of people read that story, but she got this fixation. And she was talking to me about it, and talking to me about it, and I knew she wanted to do something with it, and I was thinking, that's fine. In 1998, four years later, she got the rights to that story, and I'm still thinking that's fine for Mary. And she and John Roach started working on a script together. They went on the trip, they met Alvin's family and a lot of people. And as soon as they finished the script they gave it to me. I knew Mary wanted me to direct it, but I never really thought it was going to happen. Then I read the script and that was the end of it. It wasn't one thing that decided me, it was the whole thing. When I get an idea or read a script or a book that I love, the next thing I do automatically is "feel the air." And on "The Straight Story" the air married with the script and I knew I was going to do it.

"Feel the air." Having seen the film twice, I'm inclined to take that literally, as your reaction to the atmosphere in the story.

It's just a feeling of what's happening in the world right now -- a note, a chord, something like that in the air. It seems to be accurate but there's no way to prove that it's accurate. It's a big thing, but also sort of subtle. "Zeitgeist" -- is that what someone called it? It's the spirit of the time, and it's constantly changing, and it's fed by everybody. And you see if what you've read or fallen in love with jibes with that. It doesn't necessarily mean that the result will be commercially successful. It just means that you feel the timing is right.

Is it true that at Cannes you said you felt the potential or the need to make more gentle movies?

No, not a need -- that would be a wrong reason to do a picture. I just loved the screenplay and wanted to make it when this thing in the air supported that.

Well, I was really conscious of the air within the movie -- from the opening shots of the wind rustling through the fields and the leaves. In all your films, sound helps the audience feel what you see, and in this film I thought it also helped us understand the characters.

It's like talking is the tip of an iceberg. There's a whole bunch you can't say, but you know. And in a movie you want to carry that other thing. The story may be talking to you, but if an intuition is going, you just want to go with that. When you're working with actors you may not say so much, with words. But you're looking at the person's eyes and you're saying something and moving your hands in a certain way, and you can see some recognition suddenly appear. Then you go and do the scene again and it has now jumped, and is getting closer to this unspoken thing, which is much bigger, which is what's important. But how it happens is anybody's guess.

There certainly seem to be a lot of connections in the script that would set your instincts going -- and not just your grandfather, and driving slow. I've even read that you like sitting in chairs the way these characters do.

I love sitting in chairs!

But there's not as much weather for you to react to while you sit in L.A.!

No, there's not a lot of change in the weather, but there's good weather. And there's a certain light in L.A. I came to L.A. in 1970 from Philadelphia, and I arrived in L.A. at 11:30 at night. My destination was Sunset and San Vicente. The Whiskey a Go Go was right there; I turned left and went down two blocks on San Vicente and that's where I was going to stay until I found a place. So when I woke up in the morning it was the first time I saw the light. And it was so bright and it made me so happy! I couldn't believe how bright it was! So I sort of fell in love with L.A. right there. And I like the idea in L.A. where you can go inside but you can then just walk outside and there's no change in temperature -- it's just an inside-outside life.

There's something about sitting in a chair and just letting your mind wander. It gets harder and harder to do, but it's real important, because you don't know what you're going to wander into. And you can't try to control the wandering. You need time to think about mundane or absurd things or junk before you start getting down into something that could be useful. It doesn't always happen that something useful kicks in, but it wouldn't happen if you didn't give it a chance.

I imagine you can't do that during the making of a film.

No, then you're in a different mode, much more fast, action and reaction. A new idea could come in but it has to do with the dialogue you're having at that moment and you've got to make sure it feels correct before you leave that moment. So it's real intense, not like the period in between films.

What made you picture Richard Farnsworth in the role?

It's a thing coming through him that I think is unique. He's kind of an amazing person. He's smart but he's innocent and he's an adult but he's childlike. He feels what he says; and as he says what he says you see exactly what he's saying.

His emotional reactions become physical, like when the guy who sells him the John Deere mower tells him he's always been a smart man until now, and he cracks up -- for just a second all his dignity crumbles, humorously.

That's exactly right. You can see how things strike him a certain way. Richard could really identify with this character and this dialogue beyond what people usually say; this is one of the most perfect marriages of material and actor that I can think of.

Did you consider character actors playing older than they are?

Some actors could do that but it's riskier. There's a lot to say about an old guy playing an old guy -- they're going to bring 20 or 30 years more, or 15 years more, to it. And their face is going to be their face. Richard is just perfect.

This is the first time you've worked with the director of photography, Freddie Francis, since "Dune" in 1984. Had you tried to work with him again before this?

No, we just remained friends. I always say -- "Freddie's like a father to me. It's no wonder I left home!" [Laughter] Freddie is a crusty guy with a great sense of humor and he's always putting me down but loving me. He was a real big supporter of mine on "The Elephant Man." On "Eraserhead" there were like five people on the crew at the most; "The Elephant Man" was my first sort of regular feature and Freddie helped me out a lot. Anyway, after "Dune," he was in England and I was going off in different directions and working with people like Fred Elmes, who had done "Eraserhead." But when it turned out "The Straight Story" was coming along, I just felt it was perfect for Freddie to do. It was partly because he's one of the world's greatest D.P.'s, and partly because I wanted to work with him again, and partly because of his age. He's 82. He was a little bit worried about really long hours in the beginning, so he asked me if we could keep it to 10 hours. Ten hours of shooting means travel time on top of that. That's not a killer schedule -- 12 hours plus travel is what it usually comes down to, and travel can be a long time, if you're out and far away from base camp. But Freddie never slowed down. We worked a lot of days longer than that, and it was the younger guys who were falling before Freddie was.

I was hoping for a camaraderie on the set with Freddie and Richard, which happened; it helps Freddie to look over and see Richard and it helps Richard to look over and see Freddie. Richard looks over and sees a 35-year-old hotshot D.P., it's different; I wanted it more like a family going down the road.

However you two did it, the film does have an astonishing look.

The camera just kind of caught what was there. Out on the road there's just really one light, and that's the sun. But you can travel the road south, or north, or east, or west. The land is flat, especially in the beginning of the film, and the roads are blocked out in mile squares, they don't go diagonally. But it's beautiful to see the way the light plays going south or north or right into the sun; you can pump a little bit of light into a face but you can't go up against the sun. There are fewer choices than if you were building a set and lighting it. You go by what is there and then you get down into subtle little things based on a feeling, and that's your shot.

The whole movie is about a certain kind of American individuality. To use a California phrase, Alvin creates his own space wherever he goes. When he hunkers down in the yard of the Riordans, the people who help him fix his mower, he brings out a chair for the man of the house and says, "Now you're a guest in your own backyard." You give us a sense of the audacity of plunking down a house in the midst of these expanses; there's that incredible shot of Alvin waiting through a storm in an abandoned barn or granary, and he's both protected from the storm and seemingly submerged in it.

I love the idea of man and nature. So I love the image of a house and a person in this huge expanse of nature with clouds roiling and this kind of stuff. It's sort of what it's all about. And just that one image is about a lot of what's going on.

Although you follow the script closely, you also seem to have responded directly to what's happening on the locations -- like when the businesswoman Alvin meets on the road complains about constantly hitting deer, and looks around, and wonders, as we do, where they come from.

We picked that location for the scene, and it was a surreal spot. But the day we shot, this strange, powerful wind and weather came up, and that just added a whole other thing to it -- you couldn't choose that, it just happened for us. Film can clean up a room better than a vacuum cleaner almost -- you really have to have a messy room for it to look messy on film, and you really have to have some nasty weather for it to register. But that day there was just a mood, with the clouds, that added to the surreal quality of the landscape.

Your tendency to heighten the abstract saves the film from any hint of sentimentality. When we first see Rose staring at the ball rolling in front of her lawn and the young boy going after it, it's just a pattern -- we have no idea that she's lost her own children. The kid doesn't look at her, yet the combination of the visual and dramatic minimalism and Sissy Spacek's haunted face tugs at you. It seems like the epitome of how you want the movie to work.

It's like what I said about the dialogue between a picture and the audience. Watching a movie we're like detectives -- we only need a little bit of something and then we'll add in the rest, no problem. The portrait of Rose -- it's like in music, where you're going along, and a theme comes in. But it's only the introduction; the theme is beautiful but the rest of the music goes away from it. Then the music builds, and that theme comes back, almost in the same way, but joins with something else. And now it can destroy you.

This is also the first time that you worked with Sissy Spacek -- and with her husband, Jack Fisk, as your production designer -- even though they're both old friends of yours.

Jack is my best friend. We met in the ninth grade in Virginia. And we've been friends ever since. We were the only two in our school, with a graduating class of 750, who went to art school. Jack met Sissy when they were doing "Badlands" in '72 or '73; he brought Sissy to the stables I was setting up, when I was starting to make "Eraserhead." I have always thought Sissy was one of the greatest actresses; but it never happened that I was working on a film where a part was right for her, until this. And I was so thankful, I just wouldn't have wanted anyone else. So it finally happened. And I never worked with Jack as a production designer; I always worked with Patty Norris. But for the first time since before "Blue Velvet," Patty Norris said it was OK for her to just do costumes. It wasn't easy for her to say that, but this was perfect for Jack, so it happened.

The way Sissy does the daughter's stop-and-go speech pattern -- it never makes us laugh at her, but we do laugh, because her character almost seems to enjoy how she can focus and finish her thought no matter who interrupts.

Playing someone who is a little outside the norm and making it real is always a delicate thing. Where that becomes secondary to a thing inside the person. And Sissy just dances along the high wire and makes it look simple.

With Jack and Sissy along, it must have been even more like "a family going down the road."

All different ages traveling together, and it was beautiful. It was like the film. It took the same amount of time, we traveled the same roads, so there was another whole thing going on outside the film, behind the camera.

One story that seems to get into all your movies is "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde."

Well, Alvin changed -- he was another person and he changed.

And he compares the traumatic breakup with his brother to Cain and Abel -- who are not that far, in a way, from "Jekyll and Hyde."

And he meets up with twins -- but they're pretty much the same.

The other story that always recurs for you is "The Wizard of Oz" -- and though I know this is supposed to be a different sort of movie, I thought it entered in here too. When Alvin advises the teenage runaway to go back to her family, it's just like the scene where the fake swami (Frank Morgan) persuades Dorothy (Judy Garland) to go home.

Yes! Yeah! It really is. But I never thought about that.

And the whole movie is about a guy who offers, throughout the movie, the real wisdom that the Wizard does only at the end.

Good deal! I never thought of that. I'm sure that Mary and John didn't think about that. But maybe there's something about "The Wizard of Oz" that's in every film -- it's that kind of a story.

You do run the risk of seeming as if you're dispensing a lot of little morals.

The way I see it, it's not so much little morals, as it is about teachers and students. And that, too, is a circle, because a student has to be receptive or the teacher can't teach. And the teacher has to be intuitive and give the thing at the right moment for the student to jump. And that causes a question in the student and an answer in the teacher and suddenly there's this thing happening -- and that occurs in everybody's life.

And the film isn't trying to make Alvin's way everybody's way -- it's about doing something on your own terms and coming into full maturity and awareness at age 73.

Exactly. The way the trip is taken is extremely important -- it's a good thing that Alvin did, to do it a certain way, to let someone know how much it means.

Some lines resonate on their own -- like Alvin saying, "I'm not dead yet." But others are really tricky and two-edged, like when he tells the two young cyclists he's talking to, Steve and Rat, that the worst part of being old is "remembering when you're young."

Precisely. It's almost as if Rat goes out of his body and looks at himself for the first time. Talking with Alvin was not meaning much to him until then; to the other kid, Steve, it was meaning more. You can't know what it's like to be old until you're old, but you can get a feeling from it. So there's some of that going on there. And then, for Alvin: You can look back on when you were young as a good thing, and now it's different, or you can remember the things you did when you were young that you're paying for, or that you will.

And that pays off when Alvin and that old friend of the Riordans, Verlyn, trade horror stories -- or exchange secrets -- from the Second World War.

There's a bunch of things going on there, too. Because Verlyn tells his story first, and it's deeply disturbing. So for Alvin to tell his story is almost like a gift to Verlyn. Now, when Verlyn goes home, he won't feel bad and think, Jeez, I told Alvin this terrible thing and he just sat there. Instead, Alvin shares with him and puts himself in the same horrible, vulnerable memory spot. And, in a way, that's beautiful.

We've all been inundated with heroic clichés about the World War II generation. But here there's no inflation; the emphasis is on the emotional and psychological cost of the war.

It's just monumental that they lived with death and fear for so long, and no one else will ever know, really. But, again, you can get a feel from them. And Alvin and Verlyn can share an understanding more than they can with anybody else.

This is so much the opposite of a generation-gap movie. It's great, it's real, that Verlyn is the one who immediately gets what Alvin's going through and says, "You've come a long way." But the Riordans are terrific people in this wonderful middle period of their lives. Every generation is respected, and every age of life.

Each stage of life gives you something different. And it gets more and more internal as it goes along. The older you get, you kind of go into yourself; you don't start great big new projects, you don't do all the things you did at earlier stages. There's a lot of reflecting on the past, you kick into a different mode, and certain things that seemed real important don't seem that way anymore.

My wife and I have an ongoing debate about the relative safety of the city and the country. I always say I'm more afraid of the country, because if there's a serial killer out there he'll probably come to your house. But the countryside is peaceful in this film. Is that your Midwest fantasy?

It's not a fantasy -- and that's the strangest part of it. Once I went with Mary to Wisconsin; she's from Madison. And I go to Madison and I start meeting her family and friends, and people in the store, and I think nobody can be this nice; someone is having some sort of fun, some sort of joke. Then I realize, no, it's true. And I think it has something to do with land and farms and the fact that there's fewer people and they get to rely on one another. And this reliance has to do with survival -- they don't have any problems helping somebody, because they know that next day they could need help. Alvin did this trip and he didn't have anything bad happen to him, people did take him in and were rooting for him. You say that this is an American movie, but I'm convinced that there are people in every land who have the stuff to do that. It's certainly an American theme, but there are characters with this strength in them everyplace.

Shares