"We don't know. We just don't know. If you find out, let me know. It's a

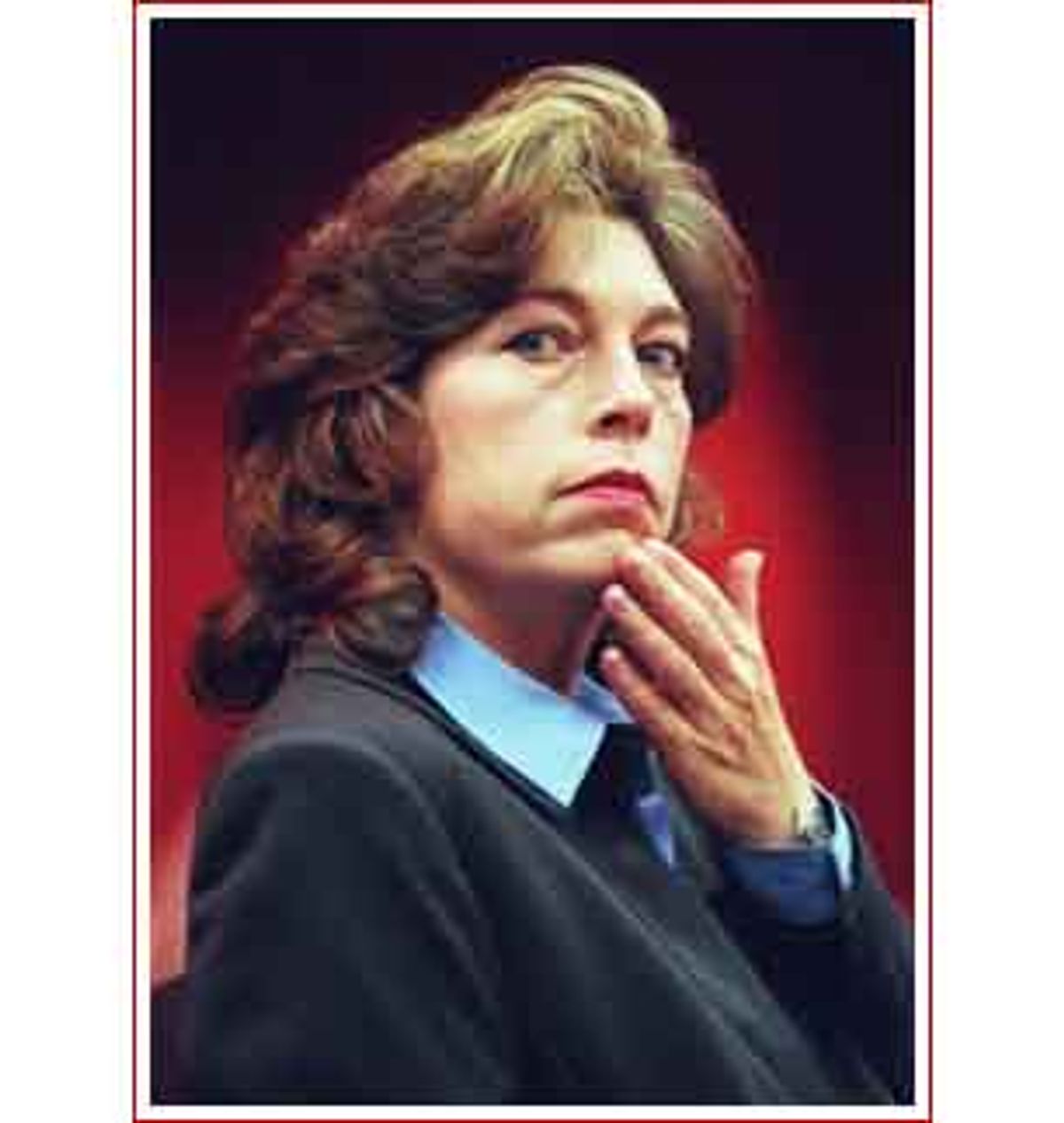

mystery." So said Marianne Gingrich, the soon-to-be ex-wife of former House

Speaker Newt Gingrich, when asked why she thought Newt was being a hard-ass in

the divorce proceedings he initiated against her.

We were talking Tuesday morning in a courtroom in the Superior Court of Washington, minutes before the latest hearing in the case, and I remarked that it was hard to

make sense of Newt's scorched-earth approach to the divorce, which has already

revealed his six-year-long extramarital affair with congressional aide Calista Bisek and tainted whatever was left of his image as a family-values Republican.

If he's pocketing $50,000 per speech, as reported, why wouldn't he just strike a deal and avoid all the negative publicity? His strategy of all-out fighting -- and dragging his new love into the mess -- seems irrational to an outsider, I commented.

"It looks that way to an insider," Marianne said with a sad smile.

Her smile was broader an hour and a half later, after Judge

Brook Hedge had ruled that Bisek had to turn over most of the records that

Marianne Gingrich's attorneys had sought from her -- including telephone bills,

credit card bills, bank statements, correspondence between her and the ex-speaker,

appointment books, gifts from Newt and other materials dating back five

years. (Neither Newt nor Bisek attended the hearing.)

Bisek's attorney, Pamela Bresnahan, had argued that the request was an

invasion of Bisek's privacy and that most of the material was not relevant to

the divorce proceedings. But Judge Hedge shot her down, noting that Bisek is "not just a

bystander" in Gingrich vs. Gingrich. Consequently, Marianne Gingrich's

lawyers -- John Mayoue, an Atlanta attorney, and Victoria Toensing, the

Republican talking head and lawyer who once counted Newt as an ally -- will have the

opportunity to comb Bisek's papers and seek out information about the secret

affair Gingrich maintained while he was rising to power.

They also will get the chance to question Bisek directly. After some

legal squabbling, Bisek agreed to submit to a deposition in December.

Earlier this month, Bisek permitted herself to be deposed by Newt Gingrich's

legal team, but Marianne's lawyers did not attend that hastily arranged

session, citing a scheduling conflict. They also wanted to delay questioning Bisek until they had received the documents they had asked her to produce.

The Newt side appeared to have set up that deposition -- "a sham deposition,"

Mayoue calls it -- so Bisek's lawyers could then claim that Marianne's lawyers

had had their chance to depose Bisek and elected not to do so. At that deposition, Bisek said that it was in 1993 that she and Newt "really started to know each other." Newt's lawyer, Randy Evans, declined to say what "know" meant in this context.

At Tuesday's hearing, though, Judge Hedge didn't fall for the deposition ploy, noting that Bisek attorney Bresnahan "can't fault" Marianne Gingrich's lawyers for skipping that

first deposition. Bresnahan decided to avoid another courtroom loss by announcing that

Bisek would sit the additional deposition.

That doesn't mean Bisek will answer all the questions, however. The hearing indicated that Marianne Gingrich's lawyers expect Bisek to plead the Fifth Amendment when she is asked about sexual relations with Newt. Because adultery is technically a crime in certain

states, she could claim that admitting intercourse might be self-incriminating.

If she takes this approach, Marianne's attorneys undoubtedly will ask Hedge to force Bisek to reply.

In the meantime, Newt has his own problems brewing with his wife's

attorneys. In August, Mayoue sent the former speaker a list of questions, a standard

procedure in the discovery process of a divorce case. Lawyers customarily try

to obtain answers to interrogatories before they hold depositions.

Mayoue's questions covered all the obvious territory. Newt Gingrich was asked to identify all persons who had any knowledge regarding his break from Marianne. He was probed about his finances, since Marianne suspects he has hidden assets from her.

He was asked to list all his bank accounts and to note all transfers of money or property in excess of $1,000 that he has made since Jan. 1, 1997. He was asked if he had received any treatment or counseling from a pastor or mental health professional in the past five years.

He was asked to identify "any and all persons, other than your wife, with whom you've had

sexual relations during this marriage" and to provide the "dates, times and places in which said sexual relations occurred." He also was asked to identify anyone who knew of these affairs. Question No. 25 inquired, "Do you believe that you have conducted your private life in this marriage in accordance with the concept of 'family values' you have espoused politically

and professionally?"

These are questions Newt presumably would prefer not to answer -- especially not for the public record. Rather than reply, he had his lawyer challenge the interrogatories. But on Nov. 15 his challenge failed, and a judge in

Cobb County, Ga., ordered Gingrich to provide answers by Dec. 5.

If the case goes to trial, it will do so in Georgia, where state law allows either party to ask for a jury trial. Imagine Marianne's attorneys grilling Newt on the stand, before a jury, about the nitty-gritty details of his relationship with Bisek; imagine them asking him to read to the court all those lovey-dovey public statements he made about Marianne and their marriage while he was cheating on her.

Why isn't Newt trying to head this ugly divorce trial off at the pass? Why are there no settlement talks occurring?

"My hunch is that he doesn't care about his public image any longer,"

says one of Newt Gingrich's associates. "He's enjoying being in the private sector, and

that means not having to worry about bad press."

This may be a sign that Newt has given up on politics. (Although talk of his political rehabilitation has always seemed far-fetched, he did refuse to rule out future runs when he announced his resignation a year ago.)

Newt-haters theoretically could have feared a Nixon-like return from the near-dead -- but given how Newt is handling this case, they need not fret any longer.

Shares