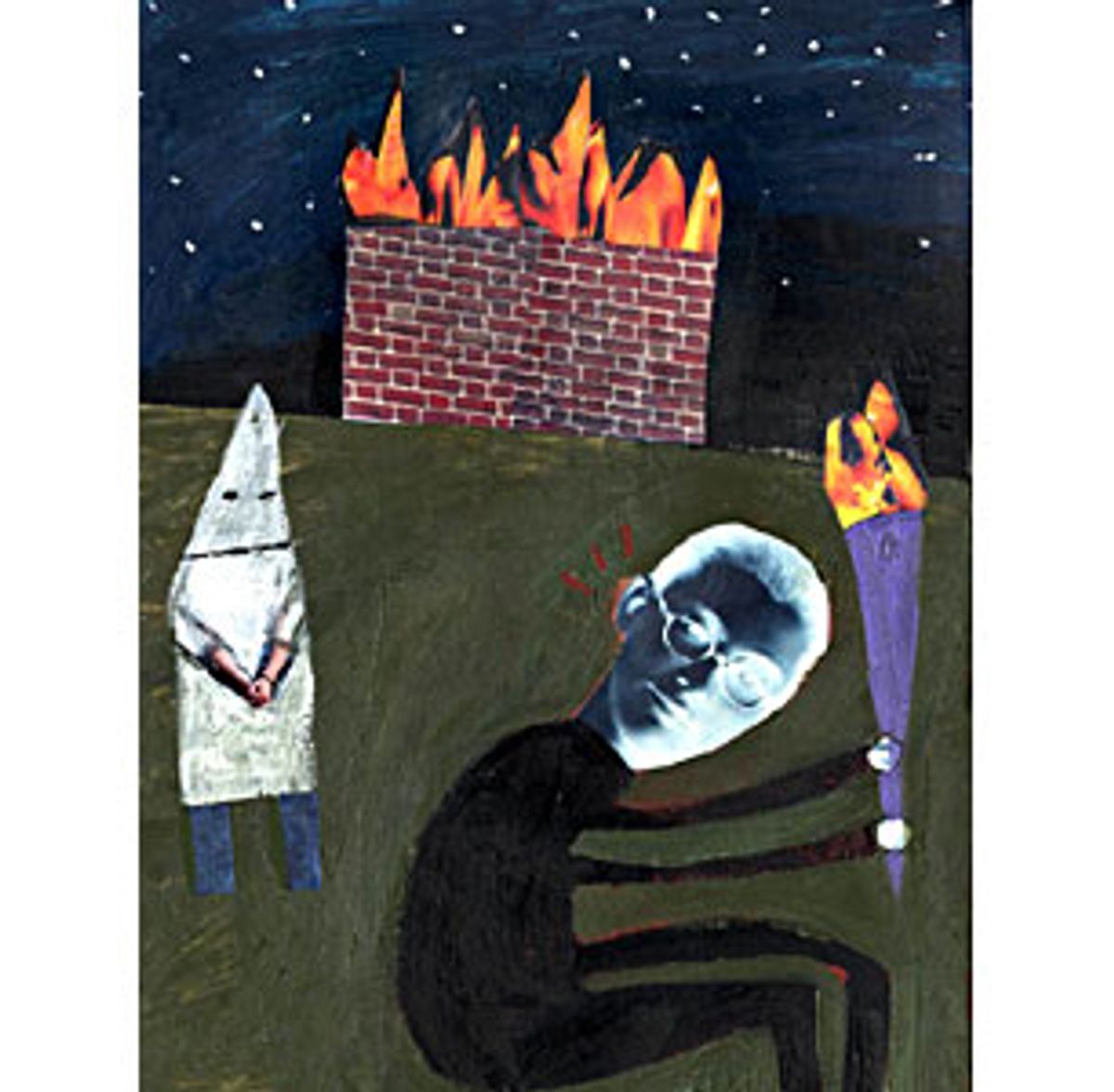

On the night of Sept. 17, 1999, near the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan, nine robed and masked torchbearers directed men and women out of their homes and onto a nearby field. Pictures of the event in a local newspaper provoked outrage, as memories of Klan intimidation darkened many minds. But the robed figures were not Ku Klux Klan members dragging black families out of their homes. They were a group of college students helping mostly white dorm residents get to an outdoor pep rally.

There were no white sheets, hooded masks, cross-burnings, bullets or hate speeches. It was just college kids in black ninja-warrior Halloween costumes with fencing masks, holding tiki torches. That didn't stop outraged faculty at Atlanta's Emory University from thinking the robed students paid homage to the Ku Klux Klan. The professors organized, mobilized and struck. It used to be students who took over buildings and held faculty hostage. Now it's faculty taking over pep rallies and holding students hostage.

Welcome to the modern university protest, Southern style.

That great university campus edict of "Thou Shalt Not Offend" rose to heights unseen since the "water buffalo" incident at the University of Pennsylvania. In 1993 a white student, woken by the loud behavior of a group of black women outside his dorm, called them "water buffalo" and invoked the campus language police.

"Robegate" has produced a jagged fault line dividing faculty and students. Most students (and to be fair, many professors) think critics among the faculty went hysterical over nothing. The faculty, in turn, is dismayed by a lack of sensitivity to the region's racist past.

The robed and masked students were part of the Paladin Society, a secret nine-member group formed by three students who were frustrated by Emory's lack of school spirit. Looking for a breakthrough event that would energize the student body, the Paladin Society and school administrators settled on a surprise outdoor pep rally at night. They chose Sept. 17 because it was the school mascot's 100th birthday and the 161st anniversary of classes.

At 8 p.m., Palladin members stood outside with their tiki torches while administrators rousted students out of their rooms with bullhorns, enticing them with the promise of a mysterious gathering. Five hundred or so black and white dorm residents were guided by the tiki torch-bearers onto a soccer field where music, food and dancing awaited them. The kids were trying to raise school spirit. They raised hell instead.

After various meetings, articles and editorials in the school paper, the controversy crested with a published letter demanding an end to the costumes and secrecy. The letter was signed by approximately two dozen of Emory's most prestigious faculty members (including a Nobel laureate).

"The public rituals and costumes of its (student) members," the letter stated, "recall the most disturbing and negative features of southern history: lynching and other forms of racial violence and intimidation sponsored by such white supremacist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan. While the current image of Atlanta is one of racial progress, until the 1940s, Atlanta was regarded as the capital of the Ku Klux Klan. The symbolism and public rituals of the Paladin Society potentially undermine Emory's commitment to diversity and progressive social change."

Right. Pep rallies attended by black and white students as a ritual with racial undertones. That kids in Halloween costumes provoked a campus-wide controversy is a measure of the racial wounds and hypersensitivity slicing through Atlanta. Memories of the KKK hang over the South's belt like a beer belly, thwarting its diet-conscious residents. No matter how Southerners try to diet -- with fat-busting euphemisms, carbo-loading amnesia or protein-shaking reconciliations -- the weight comes crashing back. This time the weight landed on a liberal campus that was once used as hospital grounds for wounded Confederate soldiers.

The modern KKK was allegedly born on Easter Sunday, 1915, in Stone Mountain, a Georgian town 15 minutes from Emory. "It sent chills up my spine," Southern history professor Dan Carter said when he saw pictures of the robed students. "And I'm white. The South has a long history of masked vigilantes wreaking havoc on African-Americans and anybody else they didn't like."

Carter, along with dozens of other faculty members, was not amused by the unintentional allusion to the Klan. But many perplexed students were right to ask, "What allusion to the Klan?" They were dressed in Halloween costumes you could buy at Kmart, for God's sakes.

The sincerity, not to mention the political persuasion of the masked students, gives this story enormous traction. Paladin Society members claim to be extremely liberal and politically correct: decent, good-intentioned students who believe in the sanctity of diversity stand accused of conjuring up the south's racist past. How did this happen? Two words: hoist and petard. The trap set by the politically correct catches the innocent as well as the guilty.

"As a minority student," said a Hindu Paladin member who wished to remain anonymous, "I'm offended at how race was injected into a completely innocent event." The student insisted the group vetted out ideas they thought would offend. None of the school's administrators involved in the creation of the pep rally had the slightest idea that their actions would be construed as grisly reminders of the Ku Klux Klan. "I grew up in southern Mississippi," said Frances Lucas-Taucher, Emory's senior vice president of Campus Life and a rally organizer. "It never occurred to me that these costumes would be so misinterpreted."

Some faculty critics such as Carter believe that a kind of Southern Jungian archetypal unconscious swayed students to produce a sinister ritual when a humorous approach would have been appropriate. "Why pick symbols loaded with evil connotations?" Critics ask. "Why black, priestly raiments and scary face masks when they could have donned festive Mardis Gras type costumes?"

Maybe because we're on the third generation of "Scream" movies? Because every third young adult dresses up like the "Scream" killers for Halloween? The movie's signature black robes and scary face mask were perfect for an event where ghost stories were told. But faculty critics were unmoved by fact or context. Once the race card is played, it's hard to put it back in the deck.

"We picked those costumes because we wanted an air of mystery, of dramatic tension," said the anonymous member of the Paladin Society. The group didn't want to do something lame. Unfortunately, "lame" is exactly how most of the students saw the rally, according to Nichole Cipriani, the school newspaper editor who attended the event. "It was pretty cheesy," she said. "They talked about Emory's history, told ghost stories and then served us Coke and Krispy Kreme donuts. There was a mass exodus as soon as it ended."

Were the students -- some of them black -- offended by the supposedly Klan-like atmosphere? "No," said Cipriani. "There were no complaints from students." Other than, the rally sucked. In an editorial, Cipriani and the editorial board told the faculty to lighten up. The editorial stated: "To connect the human abuses committed by the KKK and other supremacist organizations with an event innocently designed to bring the entire campus together is overly strident and hypersensitive. Paladin's actions were in no way motivated by racism or prejudice, the one element present in all lynchings, beatings and murders against blacks or other minorities."

One reason this sorry excuse for a racial conflict crashed on Emory's campus is because of a genuine racial conflict brewing at the 161-year-old institution. Until December, the Kappa Alpha fraternity displayed a huge Confederate flag on its front window. Kappa Alpha sits directly across the street from a black fraternity. Now that's a racial conflict. Outraged at the flagrant offensiveness, Alpha Phi Alpha, the black fraternity, asked Kappa Alpha to take the flag down, or at least put it inside the house. The KA brothers declined. Petitions signed by thousands of students and faculty fell on deaf ears. Finally, the president of KA, in direct opposition to the majority of his brothers, ordered the flag removed until the end of his term. It will probably go back up after he leaves.

The flag flap undoubtedly tugged at the hems of "Robegate." Perhaps the faculty felt impotent about a real racial problem, so they made one up. How else to explain the fact that the faculty never complained when photos of robed and masked students from DVS, another secret society, appeared in the school paper earlier that year?

"The Paladin Society borrowed their costumes from DVS," said Cipriani. "Earlier in the year, we ran two pictures (of the robed and masked DVS members) and no one said a word." Months later, the Paladin Society used the same costumes and got burned at the stake.

The Klan was a real menace in the South. Nobody is suggesting that the faculty imagined the masked horrors perpetrated on blacks and Jews. But to assert that all masked and robed figures "recall the most disturbing and negative features of Southern history" is nonsense. If you're going to complain about allusions to the Ku Klux Klan, shouldn't there be sheets, hoods, burning crosses or hate speech somewhere in the event you're criticizing? The horrors committed against African-Americans should be memorialized through sober reflection, not trivialized by foolish projection.

Shares