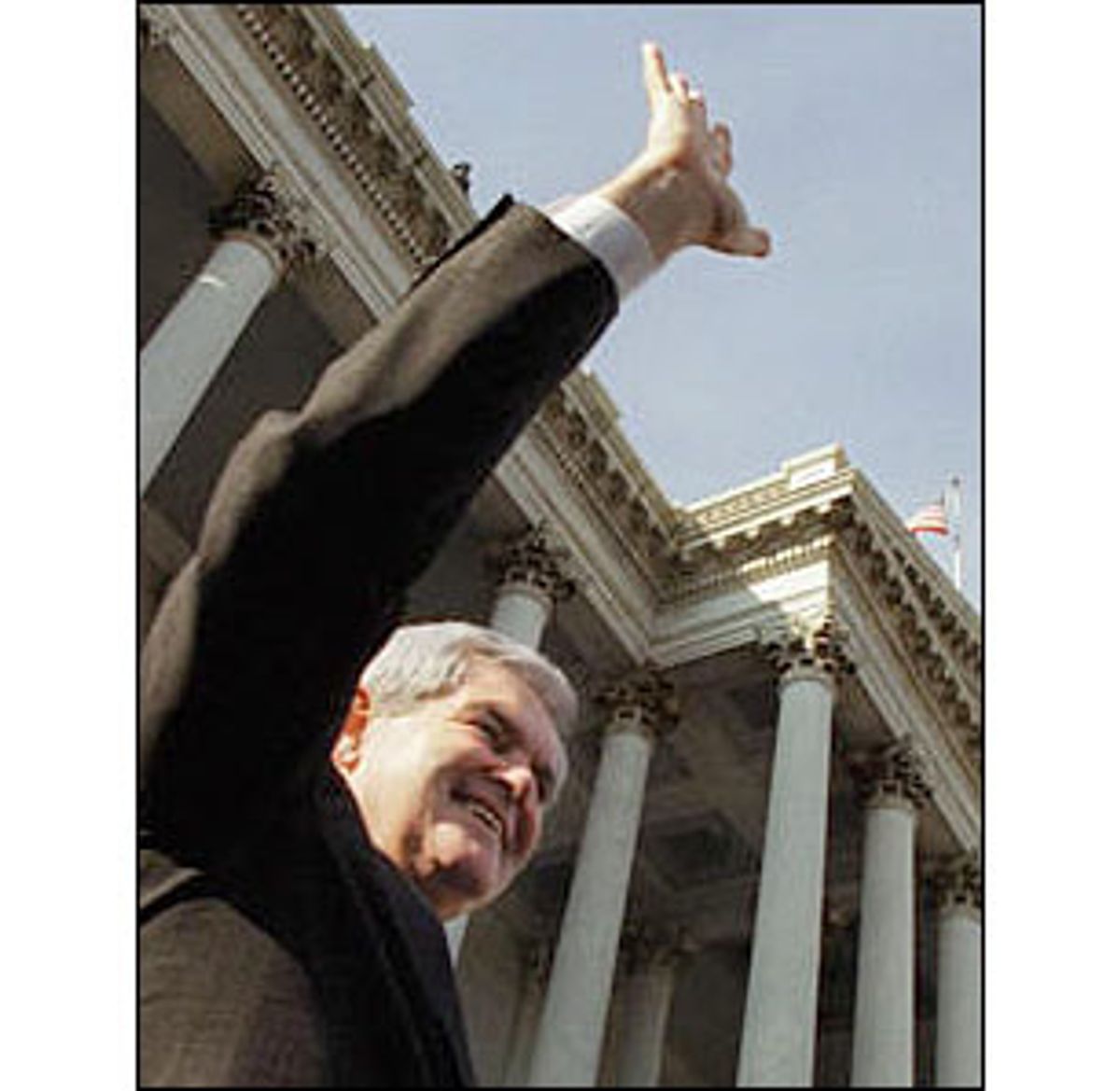

Is Newt Gingrich back? The former speaker of the House has kept a fairly low profile since resigning last year. That made sense as he underwent his second messy divorce, which revealed the affair he had maintained with a congressional aide when he led the pro-family-values Republican revolution. Now that the divorce has been settled -- with the details a secret -- he seems to be finally stepping out again, positioning himself not as a political aspirant, but as a visionary.

About 100 Washingtonians gathered Tuesday night at the center-right American Enterprise Institute, where Gingrich is a resident scholar, to hear him deliver a speech, "Reflections of a Private Citizen." The crowd included about a dozen journalists, including Donald Graham, publisher of the Washington Post, a few lobbyists (representing Honeywell and Lehman Brothers among others) and several think-tankers, such as AEI colleague Norman Ornstein. Two camera crews filmed the event. And a smiley Callista Bisek, Gingrich's mistress-turned-girlfriend, listened attentively.

It was something of a coming out for Gingrich, and he took the occasion to present himself as a big thinker. That's only natural. In the heady days when Gingrich led the GOP, he cultivated a multilayered image: He was a philosopher-historian who vowed to revive American civilization, he was a masterful political strategist and he was the champion of conservatism. These days -- his personal behavior undermining his conservative credentials, and his reputation as a tactician shredded by the House Republican failures in the last election -- all that's left is Newt the Big Ideas Guy.

But first, Gingrich offered a defense -- not of his own private-life foibles but of his tenure as speaker. He claimed the Republican Congress deserved credit for the large drop in welfare rolls. Welfare reform worked, he said, but "You won't hear this in the Gore-Bradley debates." (Actually, you do; Gore brings it up.) He also boasted that the Republicans were responsible for the explosion in stock prices. The Dow Jones average, he said, increased a puny 300 points during President Clinton's first two years, when the Democrats controlled Congress, but began a steep climb once he and his party took over.

Gingrich did concede that he had not led the House "in the right ways," and that the Republicans' performance in the 1998 elections was disappointing. He attributed this failure -- the loss of five House seats -- to a failure to develop "a second wave of ideas" to follow up on the 1994 Contract With America. In late 1997 and 1998, he said, the Republican House leadership lacked "the energy and drive" to draft a convincing second contract. Gingrich neglected to mention that he and many Republicans were busy with another matter: impeaching Clinton.

Not once did he refer to the episode. Nor did he acknowledge the possibility that the voting public became disenchanted with the policies of the House Republicans. Instead, he moved on to his mega-themes.

Big Idea No. l: "We're nowhere near the Information Age. We're at the beginning of an Age of Transition that will lead us to the Information Age."

Big Idea No. 2: "The rules of the Age of Transition are almost the opposite of the rules of Washington."

Big Idea No. 3: "The American people will pay more and more attention to the positive role of change and less to bickering."

To illustrate point No. 1, Gingrich noted that while the Wright Brothers flew the first airplane in 1903, 60 years passed before the age of mass travel. In essence, he was saying of the current high-tech era, You ain't seen nothing yet. A computer in 1955 had 80 transistors, he noted. The Pentium II chip has 7.5 million transistors. This year computer developers may succeed in constructing a chip with a billion transistors and, in 15 years, a single chip will have a trillion transistors.

"I don't know what those numbers mean," Gingrich said. "But I know they're big." What's more, he added, besides the computer revolution, there is a biotech revolution, a nanotechnology revolution and a bandwidth revolution: "Those four together will lead to extraordinary change." What these changes will be, or how we should respond to them, unfortunately, he didn't say.

He did offer a list of rules (platitudes, really) for the Age of Transition: New ideas can come from anywhere. Favor success but accept intelligent failure. Dream big but start small. Be open and more trusting. Find ways to cooperate. Give the customers what they want. Regarding the new age's emphasis on cooperation, Gingrich observed, "That's different than what's at the heart of this town." But when Gingrich was on the Hill, he was the king of confrontation and a practitioner of creative name-calling. And once, he told a group of college Republicans, "I think one of the great problems we have in the Republican Party is that we don't encourage you to be nasty." It would have been interesting to hear his reflections on his own role in Washington's culture of bickering.

Gingrich repeatedly asserted that Washington was disconnected from the real world of the Age of Transition. But he provided few hard-and-fast examples. Imagine, he explained (sort of), if there had been a conference on communication in Washington in 1900. The thrust of it would probably have been the need for a better horseshoe. But, Gingrich went on, if Henry Ford had wanted to talk about the new invention he was working on, Ford would have been told, "No, that's not a horseshoe."

What he meant by that story was unclear. He followed it by telling the crowd that recently, while addressing an insurance association, he instructed them that in a cyber-world of quick delivery times, "173 days to pay an insurance bill will not last." He also blasted doctors who keep patients waiting for hours, and predicted it will not stand in a cyber-speed era. He may well be right. But how are these 20th century irritations proof that government is sclerotic and backward?

Gingrich did glancingly refer to some policy changes he'd like to see, such as allowing people to invest their Social Security funds in the market and doubling the federal budget for scientific research and development. After all, he acknowledged, the Internet was developed by the government and the biotech revolution was launched by funding from the National Institutes of Health. (How does that square with his anti-government rhetoric? Again, it's unclear.) He then concluded his remarks with a call for ending adolescence. Yes, that's right. Ben Franklin, Gingrich reminded the audience, went to work when he was 13 years old. "We have to reintegrate adolescents into real life," he said, noting that across the country teens are starting their own computer-related businesses. Adolescence, he explained, was a "nice, interesting, 19th century invention." Once more, he was short on details.

Gingrich made no reference to his own personal behavior. But while answering audience questions, he was asked to comment on how his private life was similar to Clinton's. He attempted to cut off the question by noting he is now a private citizen, but after the audience member persisted, Gingrich paused for a moment and appeared as though he would respond. Then he stopped and began comparing his negotiating style to Clinton's: "President Clinton is very adept at moving from point A to point B in such a way he can convince you he invented point B. My weakness was I was not nearly as agile in public relations as the president." He then added, "The president is very good at demolishing his opponents."

After the speech, Gingrich was surrounded by well-wishers. He looked pleased. Grover Norquist, a leading conservative activist and lobbyist and a Gingrich confidant, gushed to me, "Is there anyone on the center-left who could synthesize like that?" But Gingrich had not synthesized. In this address, he threw out a bunch of notions, some more baked than others. Much of it was material he had absorbed and regurgitated. (To be fair, he did cite the many books and authors from which he drew.) At points, he was engaging -- but there was more gee-whiz window dressing than true illumination. Some of his familiar hubris was there, but not as much as he used to toss about. Gingrich did promise that he will soon be delivering several speeches on what he describes as "rethinking the core fabric of health."

Will Gingrich the visionary be embraced by his old fans? The Conservative Political Action Conference did invite him to speak at its annual conference later this month. And Fox News has hired him as a political analyst. But religious-right activist/presidential candidate Gary Bauer recently blasted Gingrich for undercutting the GOP's position on values. Referring to Gingrich's affair, Bauer said, "If you want to look for reasons why Republican voters are demoralized in 1999, it's exactly this sort of development." And self-proclaimed virtues czar William Bennett remarked, "I'm very glad he's not our leader anymore."

"For some conservatives, he's now radioactive," said one prominent conservative who attended the Gingrich speech. "For others, he has that magic." The speech showed that Gingrich still can impress a right-leaning audience with his lofty, high-tech, triumphant, confrontational and seemingly forward-looking rhetoric. Consequently, he may remain a player in conservative policy debates. But he still needs more practice as a visionary, if he hopes to promote his vision -- whatever it may be -- beyond the confines of Washington think tanks.

Shares