On the April 24, 1976, edition of "Saturday Night Live," producer Lorne Michaels made a now-classic appeal for the Beatles to reunite, offering a check for the hilarious sum of $3,000 ("You divide it up any way you want. If you want to give Ringo less, it's up to you") if all four Beatles appeared on "SNL" and sang at least three songs. "She loves you/Yeah, yeah, yeah," intoned Michaels. "That's $1,000 right there."

The Beatles didn't come together for "Saturday Night Live" (although George Harrison did appear in a skit on a subsequent episode trying unsuccessfully to claim his share of the $3,000). But in their book "Saturday Night: A Backstage History of 'Saturday Night Live,'" Doug Hill and Jeff Weingrad report that John Lennon and Paul McCartney at least gave Michaels' proposal a passing thought. The authors quote a Playboy interview with Lennon shortly before his death in which he confirms that he did indeed watch Michaels' original "Saturday Night Live" pitch -- with McCartney, who happened to be visiting him at the Dakota. Said Lennon, the two thought the whole idea was so funny, "We almost went down to the studio as a gag."

The new VH1 movie "Two of Us" takes off from that anecdote to dramatize what might have transpired between Lennon and McCartney during that 1976 meeting at Lennon's New York home. What if this was the first time they'd seen each other since the Beatles' bitter break-up six years earlier? What would John and Paul say to each other? Well, as "Two of Us" screenwriter Mark Stanfield imagines it, the reunion occurs on a whim when Paul (Aidan Quinn), who is in New York doing publicity for his band Wings' upcoming Madison Square Garden stint, suddenly has his driver stop in front of the Dakota. He arrives unannounced to find Lennon (Jared Harris) sulky, suspicious and conveniently alone -- Yoko and baby Sean are off buying a cow, for some unexplained reason.

"So, here we are," says Paul, all Paul-cheery. "Yeah," replies John, all John-acerbic. "You, me and everything between us." When Paul asks him what he thinks of his latest Wings single, John replies, deadpan, "Well, you would have thought that people would have had enough of silly love songs." Advantage, Lennon.

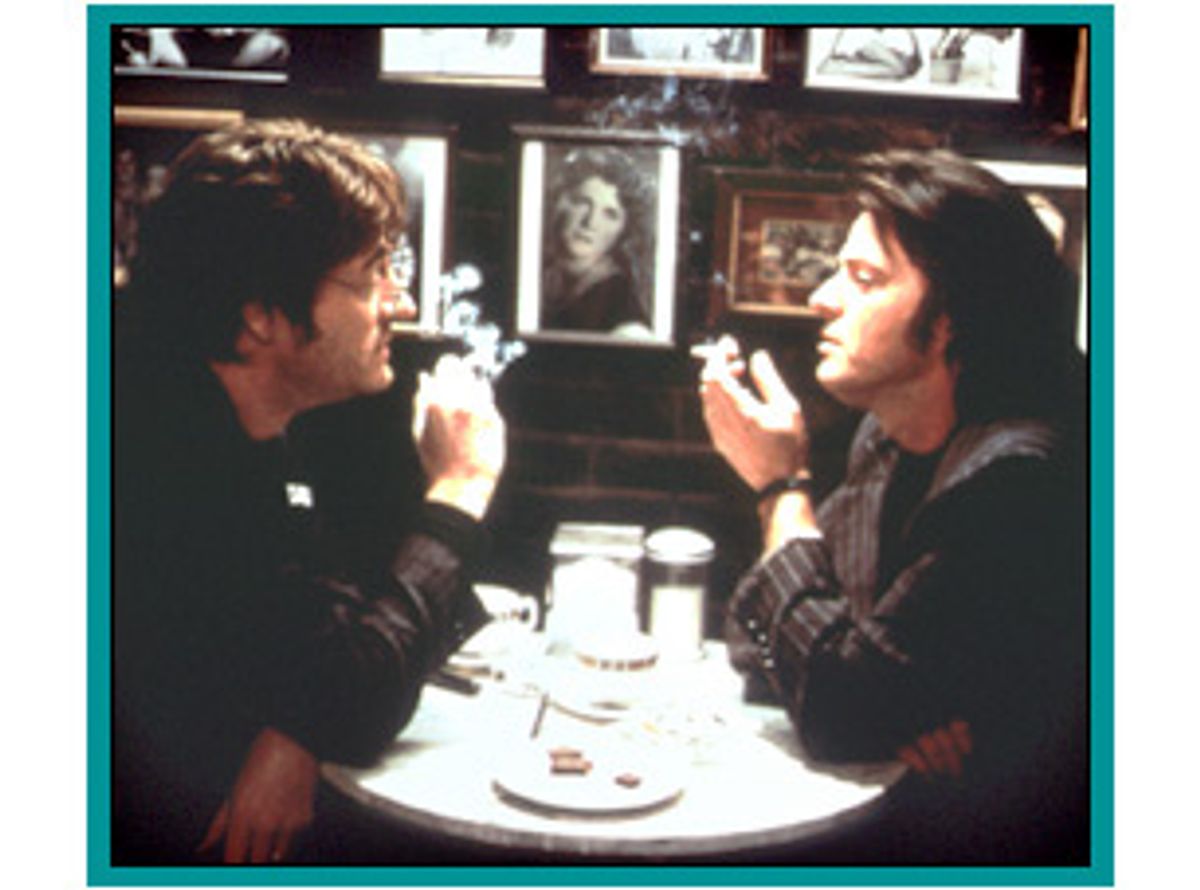

Paul remains as patient as a saint, however, and eventually his puppy-dog-eyed enthusiasm wears Lennon down and they have some tender Beatle Fan Fiction moments, where John pours his heart out about his terrible childhood and Paul soothingly tells him, "I see a frightened man who doesn't know how beautiful he is." They sip tea, meditate, smoke some dope, pop some popcorn, go for a skip in Central Park ("disguised" in mustaches and matching bowler hats). And then they snuggle down in front of the tube to watch "Saturday Night Live." Beatles reunion? This is more like a Beatles pajama party.

Directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg, who chronicled the final moments of the Fab Four in his documentary "Let It Be," "Two of Us" is a rather pointless piece of Beatle lore at this late inning. The mercurial, tortured Lennon has already been sufficiently what-iffed in Iain Softly's 1993 drama "Backbeat" (which depicts the tension, sexual and professional, between John and early Beatle Stu Sutcliffe) and in Christopher Munch's 1991 short "The Hours and Times," which speculates what might have happened on a Spanish vacation Lennon took with the Beatles' gay manager, Brian Epstein, in 1963. In fact, "Two of Us" coyly references "The Hours and Times" in a scene where Lennon, horsing around, kisses McCartney on the mouth, and McCartney, wiggling away, cracks, "Is my name Brian?"

But, really, hasn't the whole "lovable Paul vs. difficult John" theory of the Beatles' dynamic passed into moldy pop myth by now? Can any of us on the outside looking in pretend to know what went down between those two? And isn't it about time we all just, you know, let it be? "Two of Us" doesn't reek of exploitation, like the hideous 1985 TV movie "John and Yoko: A Love Story." But even though "Two of Us" is an affectionate, respectful piece of work, there's been a lot of water under the bridge by now, and the movie can't avoid slipping down into the soggy, maudlin drink. A mounted policeman in Central Park ominously warns John and Paul to be careful because there are "a lot of crazies out there"; Paul goes on and on about how lovely life is with Linda. Oh, if only they knew what was coming, we sniffle into our Chee-tos.

Still, soapy tear-jerking aside, "Two of Us" does manage to convey the sense of dislocation friends feel when a friendship is falling apart. In one heated back-and-forth, Lennon tells McCartney, "When I met Yoko, everything changed. I couldn't care less about being in some little boys' club anymore." McCartney replies bitterly, "You bloody disappeared! ... You were spending all your time with Yoko. I felt like I was losing me best mate!" And the movie does a credible job of depicting the toll youthful, wild success took on Lennon and McCartney, and how they spent their post-Beatles lives trying to grow up and find the men inside the mop-tops.

Quinn makes a charming McCartney, uncannily capturing the cadence of his Liverpool accent, his boyish energy and his wide-eyed, spacy sweetness. Harris ("I Shot Andy Warhol") is less of a physical match to his character -- his features are too hawklike and brutish. But Harris gives a strong, unsentimental interpretation of Lennon as an emotionally needy man-boy; the scenes where John cruelly toys with fans in a neighborhood cafe, and curls up on the floor whimpering into the phone to Yoko ("You're the only thing that keeps me from disappearing") put a chill around your heart. No matter how many times Lennon's story gets told, the ending will be the same; we'll never know for sure if he ever made peace with himself.

And that's the real allure of these dead rock star biopics, from all those Elvis TV movies to Oliver Stone's "The Doors" to Melissa Etheridge's upcoming Janis Joplin movie -- celebrities take up residence in our consciousness and then when they're suddenly not there, we're bereft. We feel robbed of -- no, entitled to -- the big What If. What if the Beatles had reunited; what if Elvis had gotten off the pills and slimmed down; what if Kurt Cobain hadn't pulled the trigger? What if fate could be altered, mysteries solved, questions answered? Of course, if these dead celebrities had stuck around, we wouldn't have the luxury of posthumous speculation, would we? They'd be problematically alive and imperfect, year after year, comeback album after comeback album, reunion tour after reunion tour. We'd probably be complaining about how old and fat and boring they are.

Which brings us to former Sex Pistol John Lydon, aka Johnny Rotten, and his occasional VH1 TV series "Rotten Television," which premiered Jan. 23. Rotten, who may be old but is neither fat nor boring, is up to his familiar tricks in "Rotten Television" -- he's still dedicated to mocking the pop culture and media machinery that turns citizens into sheep. But what he really seems to relish these days is slagging off other rock stars who, in his unforgiving opinion, have gotten too big for their britches.

In the Jan. 23 episode, Rotten skewered Neil Young viciously (no pun intended), donning a plaid shirt, long sideburns and shaggy wig to mewl, "The King is dead but he's not forgotten/This is the story of Johnny Rotten." The reason for this Neil-bashing? Young turned down an invitation to be on the show, allegedly conveying through handlers that he only talks to people he knows. Now, Mr. Rotten took offense at this remark, and can you blame him? Young obviously felt like he knew Rotten pretty well when he made him the centerpiece of "My My, Hey Hey (Out of the Blue, Into the Black)," and now he won't talk to him. Rotten gleefully adds Young to his roster of "fakes and frauds," and whether you agree with him or not, you have to respect his in-your-face obnoxiousness, still robust after all these years. Nobody is ever going to elevate this deliberately unlovable nay-sayer to TV movie sainthood. Johnny Rotten will forever remain a slob like one of us, which, I'm guessing, is OK by him.

In "Rotten Television," which is scheduled for six more episodes this year (no air dates have been set yet -- perhaps VH1 is waiting to see how many slander suits the first episode brings in), Rotten makes an admirable if messy attempt to translate his philosophy ("I'm just telling you like it is, no lies, no fakes no fraud") to TV. Rotten strives mightily to provoke; in the first episode, he savaged not just Young, but other stars who base their images on "honesty." He referred to Courtney Love (another desired guest who turned him down) as "Courtney Loves Kurt's Money," taunting, "You love the idea of being a rebel but you haven't proved to me or anybody what you're rebelling against. You're just a pile of confusion, ya cheap fake!" Will Love take the bait? Gosh, I hope so.

But the first episode was, to delicately put it, uneven. In a disappointing -- OK, pathetic -- segment, he showed up for a guest spot on Roseanne's talk show with a camera crew in tow, Michael Moore-style. He picked a fight with the producers for not letting his crew film rehearsal as promised, acted as snottily as possible and got thrown out, the point being that Roseanne's employees can't take his punky attitude, although Roseanne has cultivated quite a punky attitude herself. Duh.

Much more cutting was the segment where he railed against rock 'n' roll memorabilia auctions, blowing up a pile of presumably priceless artifacts, including what he described as a genuine Sid Vicious suicide note, proclaiming, "It's what these people have done that is relevant, not what they wore while doing it." Rotten also made an appeal for viewers to visit the "Rotten Television" Web site and tell him to piss off -- he promises to answer all e-mails.

And he administered a dose of tough love to ordinary celebrity-worshiping, trend-following folks. In a filmed segment documenting a casting call for "Rotten Television" VJs (no such position exists), Rotten illustrated his very sound theory that "it's not about who does anything anymore, but about who presents it." Seated behind a desk talking through an old-style Hollywood director's megaphone, he interviewed a succession of attractive airheads who wanted to be VJs because they were such huge music fans. He stumped two of them with the question "Who played bass in the Beatles?" It was a clever, nasty bit of cultural commentary. Rotten Johnny Lennon might have enjoyed it.

Shares