Happy Valentine's Day! Please don't buy your sweetheart a copy of Seduction and Spice, by Rudolf Sodamin, unless you give a box of Handi Wipes along with it. This elegant-style tome, which is bound in what appears to be red Ultrasuede with endpapers that do not look like hammered 24-karat gold although I know the publishers wish they did, all but drips as you turn the pages.

"The idea of an aphrodisiac cookbook has haunted me, flirtatiously darting in and out of my mind, for years," writes Sodamin. "Like a temptress, the concept has teased me, coquettishly calling out to me while I'm selecting fresh fruits and vegetables, pinching the border of a pie crust, or staring into the eyes of my lovely wife, Bente." (Staring into your wife's eyes makes you want to write a cookbook?) Speaking of those fresh fruits and vegetables, my 15-year-old daughter screamed aloud when she read Sodamin's take on avocados: "This fruit echoes the soft curves of a woman yet is also reminiscent of a man's nether regions." EWWW! Mr. Sodamin, shut up! But he just keeps going.

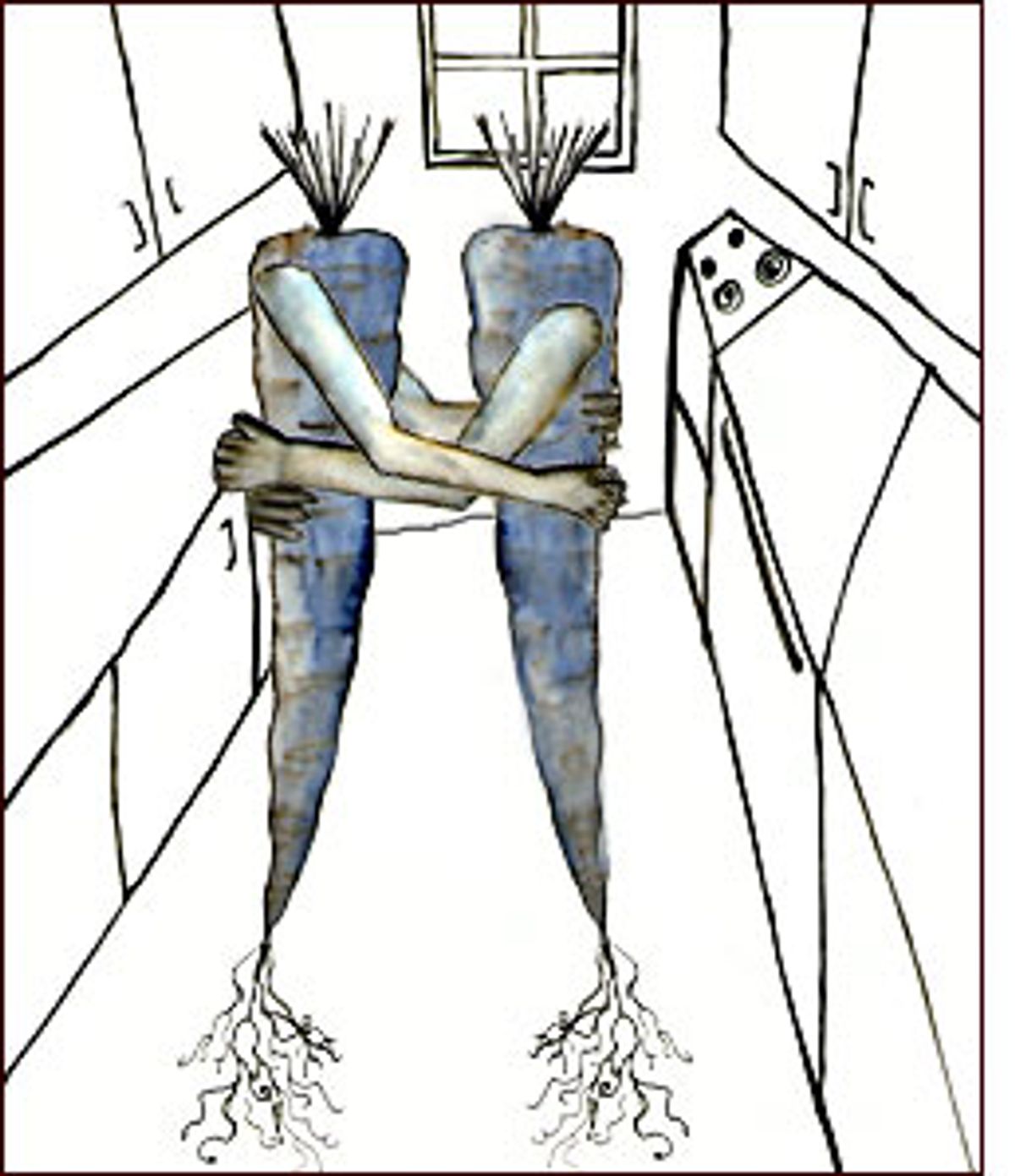

Potatoes are "the testicles of the earth." Asparagus is "a fine, firm phallic symbol." "Carrots are a prime source of vitamin A, a necessary nutrient in the production of sex hormones in both men and women. In men, vitamin A contributes to a healthy prostate and increases the number of sperm in each ejaculation." He doesn't leave out the ladies, either. "With Middle Eastern sesame treats such as halvah and tahini now widely available in most supermarkets, exotic foreplay was never so tasty. Women find sesame especially enlivening." (No, they don't.) Medieval maidens "imprinted their intentions onto bread dough by pressing it against their vulva before baking." Funny -- I don't find these passages arousing.

Elsewhere Sodamin's ejaculations don't even make sense. Of thyme, for instance, he writes that the herb's assertiveness "pays off sometime after dessert, when you two are getting to know each other better." Of eggs: "Today the Japanese favor rich quail eggs, while Filipinos patiently give their eggs a bit more time in the nest, as they believe duck embryos are a source of sexual vitality." And lobster: "The greenish blue beasts will blush bright red when boiled, as you might when your mate gets you home." And boils you? The recipes in the book are fine and the photography is, of course, darned sexy, but I don't care. I wasn't a bit sorry when my daughter took a black permanent marker and turned the avocados on page 13 into cute little mice.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Love occasionally besmirches the pages of the otherwise respectable Kitchen Suppers, by Alison Becker Hurt. It's just somehow more than I wanted to know that Hurt's husband calls her "Little" and she calls him "Bigger One." But the book's basic concept is nonetheless appealing. Hurt is the owner of two restaurants -- Alison on Dominick Street in Manhattan and Alison by the Beach on Long Island -- and might therefore have been expected to turn out one of those showoff coffee-table books favored by some restaurateurs. But she's gone in the opposite direction, and it's a refreshing change.

"When I married my husband," Hurt writes, "we inherited the kind of large, formal dining-room table I had always dreamed of, with repoussi Kirk silver and miles of lace napkins, tablecloths, and runners. I love to cook, and I loved the idea of cooking grand and graceful dinners, and I did -- twice." Then, sick of soaking the tablecloth in the bathtub and washing flatware for three days, Hurt threw in the lace towel:

The food had been splendid and a good time was had by all, but I learned that this exercise in grandeur and gracefulness was only that. It seemed to take the heart out of creating the meal by causing too many worries and complications. And it was not about cooking, which is what I really love to do. Realizing this, I ran back to the comfort and safety of my checkered tablecloths and what I like to call "kitchen suppers."

I came to exactly the same conclusion -- after way more than two formal dinners, alas -- which is why my husband and I are still married and why we now have a pool table in our dining room. (Note to any readers contemplating marriage: Don't register for crystal. It all breaks. Just get regular wine glasses that you don't care about losing.) The recipes in "Kitchen Suppers" are appealing and fashionable without torturing the family cook. Eye of round with orange cream and horseradish; a gin-scented tomato bisque; roast duck with cinnamon stuffing, tangerine juice and honey wine sauce -- the emphasis is on hearty, simple foods that are also pleasantly novel, and their names are the only cumbersome thing about them.

Still, there's a little too much talk and not quite enough recipes. I love cookbook chat, but half the chapters in "Kitchen Suppers" are devoted to basics that have been covered more than adequately elsewhere. The difference between poaching and braising ... what a brandy glass looks like ... the facts that a centerpiece should not dominate the table and that you should clean the kitchen as you go along and that "loaf breads are made in pans" ... Anyone buying "Kitchen Suppers" is likely to own "The Joy of Cooking" already, and "Joy" has all this information in far more detail (as Hurt surely knows, since she is related to Marion Rombauer Becker, one of the coauthors of "The Joy"). There's a slight mismatch between the text's primer-like tone and the recipes, which, though simple, would not be easy for the novice cook. The spot art here and there -- a pig, a basket of flowers -- contributes nothing except a faint girlish sweetness. Doubleday's designers would have served the book better with actual illustrations.

On the other hand, the basics aren't always spelled out fully enough. In the wine chapter, Hurt explains that "if you have a computer and are on the Internet, you can go to many different wine-related Web sites, including the Wine Spectator site" -- she doesn't provide its address -- "and ask questions. Someone somewhere out there will e-mail you his or her ideas about the perfect wine to go with your dinner." This doesn't strike me as a reliable solution. Nor is Hurt's description of how to select a cheese. "Cheese is not supposed to be bitter or sour. If it is supposed to be a 'stinky' cheese, it may taste similar to the way it stinks, but even so, the flavor should be a bit milder than the stink." I'd like for Hurt's next book to be more grounded than this, and it should have more of the recipes she's so good at creating. Still, "Kitchen Suppers" is a promising debut, as I believe reviewers are required to call first books.

As Alison Hurt has learned, these days it's tough to write a cookbook for the general public because it's so hard to assess what your readers already know. The current thinking has it that no one cooks at all, no one knows how to hold a fork or what a napkin is, and as for gutting a fish, forget it! I mean, if they had a video game about gutting fish, or a takeout guy who could gut the fish for you, then maybe, but I mean if you go to a fish store it's all fileted already, and how's anyone supposed to learn anything that way?

Don't you hate people with opinions? I do. Anyway, many cookbook authors seem to believe that their readers are either four-star chefs or idiots with catchers' mitts instead of hands. Fortunately, James Peterson is able to conceive of a middle ground where readers know the culinary basics but want to learn more: hence his Essentials of Cooking, which contains 250 "core techniques and recipes" and more than a thousand photos. And finally! Photos that aren't beautiful -- that are even ugly when they need to be! I'm through with gorgeous photography that does nothing besides raise the book's price and prove that the publisher could afford a food stylist. Here, instead, is a sort of Field Guide to Culinary Technique, with close-ups of hands doing everything hands need to do in the kitchen -- chopping garlic, poaching seaweed, peeling roasted beets, de-tendoning chicken breasts, butchering a double rack of lamb ...

Peterson explains:

Because I've wrecked entire afternoons screwing together my own garden furniture and bookcases, it's easy for me to imagine one of my poor readers, string in hand, trying to truss a chicken and after ten minutes, forgetting trussing and moving on to strangling. So I decided to illustrate certain techniques with an almost obsessive number of color photographs. I've tried to make the photographs cheery (see how easy this is!) and life-like -- they were shot under real-life conditions in my cramped Brooklyn apartment -- so that if the going gets rough, things won't seem utterly hopeless.

But his work is so clear that it's hard to imagine going astray with this book in front of you. The only concession to art (and I mean this in a nice way) is the page of photos facing the Acknowledgments. Everything else is clean and well-lit, like a Clinique ad, but supremely utilitarian.

"Essentials of Cooking" is organized in the same sensible way. It has only six chapters: "Basics," "Vegetables and Fruits," "Fish and Shellfish," "Poultry and Eggs," "Meat" and "Working From Scratch." ("Working From Scratch" shows you how to gut a fish, by the way.) Technique is what's emphasized, not recipes. "Once you've gotten a handle on roasting, poaching, grilling, frying, steaming, sautiing, and braising, you'll know how to cook most food, and if you understand the logic of how these techniques work, you'll be able to improvise intuitively and give your own special style and identity to your cooking." Not necessarily; you can have plenty of technique and still lack the improvising gene. But once you've learned the technique it's a lot easier to go to conventional cookbooks and steal their improvisational skills. I can't imagine saying this about many other cookbooks, but "Essentials of Cooking" really is essential. Even if you think you already know enough about cooking, I command you to buy a copy right now.

Shares