It had to happen eventually. Michael Douglas, Mr. Crisis of '90s Masculinity himself, the movie star who seems, paradoxically enough, to be widely loathed, has made a film in which he looks like total crap. I mean, on purpose. (My significant other claims that the real human-rights violation in Paul Verhoeven's "Basic Instinct" was not its representation of lesbianism but its all-too-flagrant display of Douglas' bare ass.) Shambling through the wintry Pittsburgh of "Wonder Boys" as decaying novelist Grady Tripp, unshaven, unkempt and frequently clad in a fuzzy pink woman's bathrobe, Douglas actually resembles a middle-aged human being for the first time.

This is such a shock because most of Douglas' previous characters are guys whose entire raison d'jtre seems to be avoiding the aging process. Grady, on the other hand, is long past meltdown; he hasn't just gone to seed, he looks like he's got mushrooms growing in his ears. He's still a soul in anguish -- maybe Douglas can't help bringing that to his character -- but it's a pretty genial, vague, marijuana-steeped anguish. Grady is the genuinely likable if profoundly flawed hero of this literate upscale entertainment, adapted from Michael Chabon's novel by Steve Kloves and directed by Curtis Hanson, whose last film was the atmospheric if haphazard "L.A. Confidential." With a cast this terrific and a story this rich and wry, "Wonder Boys" really can't miss, even if it thumps to an underwhelming and moralistic ending that undoes a fair amount of its goodwill.

From the imitation-noir mode of "L.A. Confidential," Hanson here moves into the life-lessons epic mode that Lasse Hallstrvm has mined so successfully, both in his current "The Cider House Rules" and in "What's Eating Gilbert Grape."

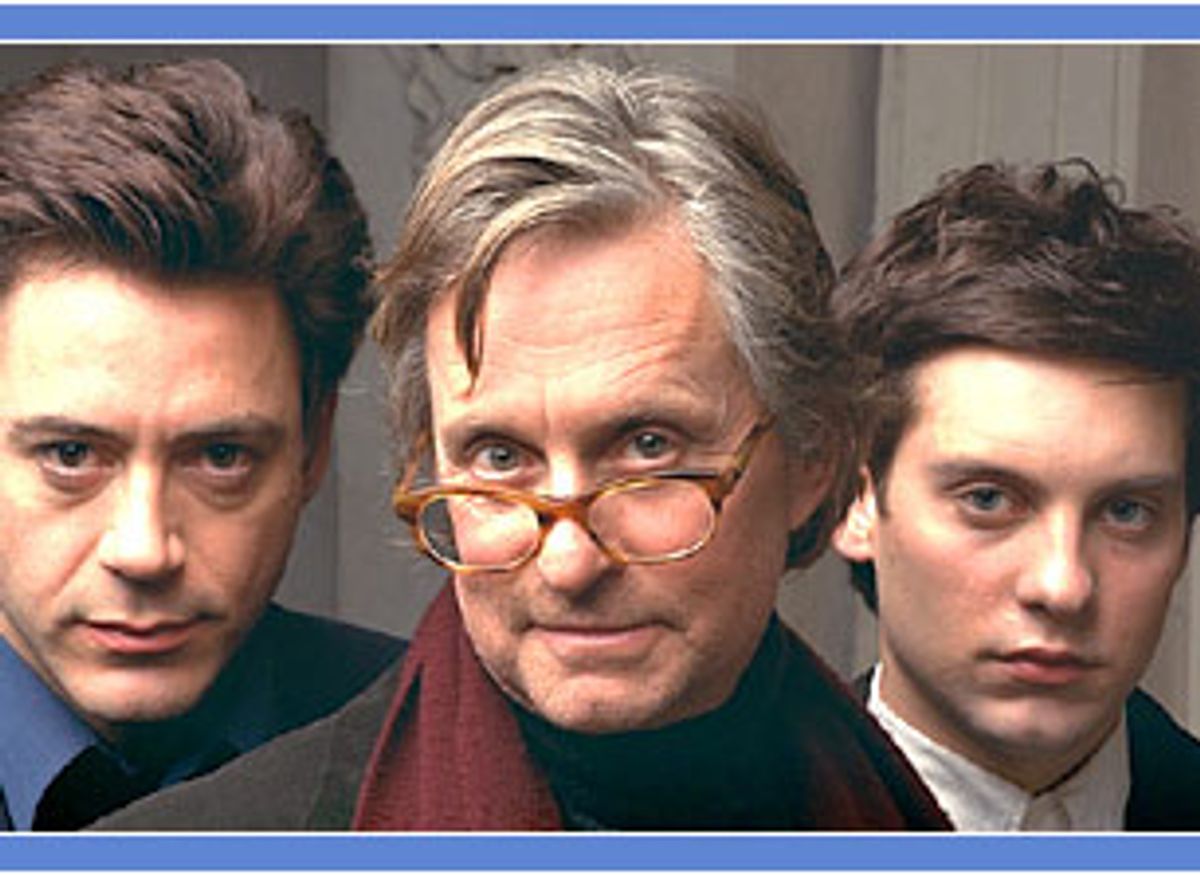

If "Cider House" argues vehemently that abortion can be a humane and moral decision, "Wonder Boys" may be remembered for its naturalistic depiction of an American milieu in which homosexuality doesn't faze anybody. Grady isn't thrilled that his sleazeball New York agent, Terry "Crabs" Crabtree (Robert Downey Jr., whose real-life debauches have opened up an entire second career for him), winds up sleeping with James (Tobey Maguire), the prize student from his Carnegie Mellon creative-writing class. But the fact that both are male is presented only as a complicating factor, not an outrage, a secret or a statement of any kind.

In any case, Grady has larger problems than the consensual entanglements of his friends. His young and beautiful wife has left him, and in fact never appears in the film (although her friendly parents do, played by Philip Bosco and June Hildreth). It's been seven years since he published "The Arsonist's Daughter," a much-celebrated novel that brought him a literary reputation and tenure. He has indeed been writing its follow-up -- and writing and writing and writing -- to the tune of 2,000 weed-fueled pages, with no end in sight.

He's in love with Sara Gaskell (Frances McDormand), the married university chancellor, who has just told him she's pregnant with his baby. When Crabs shows up in Pittsburgh, with both his Manhattan snarkiness and a transvestite hooker in tow, Grady gradually comes to realize that his seemingly invulnerable old friend is falling apart too, and is reaching to Grady for a lifeline.

But the essential drama and comedy of "Wonder Boys" emerge from the halfhearted odyssey that Grady and James embark on together, as they travel through the frozen streets of Pittsburgh with a dead dog, a pistol, a jacket once worn by Marilyn Monroe and a Ford Galaxie 500 of dubious provenance. Sometimes they're pursuing Grady's missing wife and sometimes they're after Sara, whom Grady knows he has to face eventually, but most of the time they're just driving around getting baked. Maguire pretty much does what he always does, playing James as a cryptic, almost affectless loner whom we somehow know needs affection and understanding. I don't understand why I'm not tired of his shtick, but I'm not. Something in Maguire's arch, tense and injured frame is inexplicably expressive; I think he's the James Dean of the year 2000.

James may be gay, may have suicidal tendencies and is very likely a compulsive liar: He spins yarns about growing up in a blue-collar Pennsylvania town whose only employer was a mannequin factory, when his real parents are revealed to be WASPy socialites. What most concerns Grady is that James may also be on the verge of discovery as the next "wonder boy," or hot young novelist. (There's an irritating, faux-naive presumption in "Wonder Boys" that men write and women deal with them the best they can.) Grady's too stoned most of the time to sort out the mixture of pride, jealousy and simple affection he feels for James; he's never sure whether he wants to destroy James or nurture him (or whether he's capable of either), but he can't leave him alone.

If Downey's flamboyant, often hilarious performance tends to suck up all the oxygen in the scenes he's in, McDormand is nicely understated in another of the relatively low-profile roles she has pursued since winning a best-actress Oscar for "Fargo." She's such a fine actress that seeing her composed, controlled mask of worry and weariness is all you need to understand Sara -- and that's a good thing, since Kloves' script gives the role short shrift. Sara is essentially a stock figure from 20th century American male psychodrama: the adult woman who demands that the men around her grow up and take responsibility for their own lives. "I'm not going to draw you a map," Sara rather grimly tells Grady. "At times like this you have to do your own navigating." If McDormand wasn't capable of balancing her emotions, and the audience's, on a knife-edge, Sara could easily have become a caricature. In the other female role of note (also underwritten), Katie Holmes makes a fine impression as an ambitious undergrad who wants more than mentorship from Grady.

As I suggested earlier, Hanson's most important job in "Wonder Boys" was to show up, turn the camera on and let the uneasy on-screen relationship between Douglas and Maguire, two actors of vastly different temperaments and generations, bear its peculiar fruit. But if there's one thing Hanson learned during his early career making crappy thrillers like "Bad Influence" and "Bedroom Window" -- and anyone who wants to promote him as a great director needs to rent those -- it's the importance of setting. He and cinematographer Dante Spinotti capture both Pittsburgh (one of the most serendipitously beautiful American cities) and the netherworld of boho academia with brilliant precision. If you went to a liberal-arts college anywhere in the United States, then the way Grady's ramshackle house looks in the wake of Crabs' enormous all-night party should conjure up vivid sense-memories.

Ultimately, however, there are some intractable problems with this baggily enjoyable movie. Douglas' Grady, although the character represents one of the actor's finest performances, is essentially a steady-state universe. We know he's supposed to change and come to grips with his failed marriage, his failed novel and his potential future with Sara, but it actually seems far more plausible that he won't. For me, at least, the abrupt resolution of Grady's various quandaries seemed forced and obvious, as if midlife-crisis management were mostly a matter of getting a haircut, laying off the ganja and trading in the fuzzy bathrobe for some tasteful Italian sweaters. (Chabon's novel, with its greater length and range of episode, works toward a much smoother conclusion.) For all its delights, "Wonder Boys" begins to leak out of its frame by the end, eager to remind us that Douglas is not the dissipated Grady Tripp or even just an actor but one of the most powerful men in Hollywood, apparently ageless and invulnerable, with Beauty on his arm and Time at his command.

Shares